In the intricate world of biomolecular detection, few methods have achieved the ubiquity and transformative impact of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This cornerstone technique leverages the precise dance of antigen-antibody binding, amplified by enzymatic signals, to deliver highly sensitive and specific detection of targets ranging from disease biomarkers to environmental contaminants. Its elegance lies in converting molecular interactions into measurable signals, making it an indispensable tool in clinical diagnostics, biomedical research, and beyond.

However, the apparent simplicity of an ELISA protocol can be deceptive. The reliability of its qualitative or quantitative result is not a given; it is a carefully orchestrated outcome that hinges on a deep understanding of its biochemical principles and vigilant control over a multitude of variables, from sample handling to data analysis.

This article delves into the fundamentals of ELISA. It systematically explores the critical factors that determine its success, empowering researchers to transform this common technique into a pillar of robust and reproducible science.

Table of Contents

1. What Is ELISA?

The ELISA is a widely used immunological technique that detects and quantifies a specific target antigen or antibody [1]. It relies on the specific binding between an antigen and its corresponding antibody, with qualitative and quantitative analysis achieved via an enzyme-linked antibody that catalyzes a colorimetric or chemiluminescent reaction upon substrate addition.

ELISA is extensively applied in various fields, including basic scientific research, clinical studies & diagnosis (e.g., biomarker detection, disease monitoring, infectious disease testing, allergy screening, hormone level measurement), environmental monitoring, food safety, and drug development.

Figure 1. The ELISA technique is used to detect an antigen in a given sample (The antigen is added to the microplate wells and captured by the immobilized antibody. The primary antibody binds specifically to the captured antigen. An enzyme-labeled secondary antibody is introduced and then catalyzes the color-producing reaction upon addition of a chromogenic substrate, yielding a color change to quantitatively or qualitatively detect the antigen.)

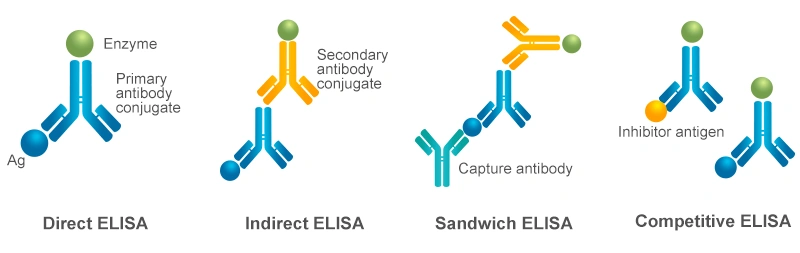

Depending on the experimental design and detection objectives, ELISA can be classified into four primary types: direct ELISA, indirect ELISA, sandwich ELISA, and competitive ELISA [1,2]. These types differ in the way and steps of antigen-antibody binding. Based on different purposes, ELISA can also be classified into quantitative and qualitative methods. The choice of ELISA format depends on the nature of the analyte and the available reagents.

The fundamental step in the ELISA assay involves immobilizing the target antigen or an antigen-specific capture antibody directly onto the microplate well surface, which enables the direct or indirect detection of the antigen. For highly sensitive and specific measurements, the target antigen can be selectively isolated from a complex sample using an immobilized capture antibody. This captured antigen is then bound by a separate detection antibody, forming an antibody-antigen-antibody sandwich complex.

When the target antigen is small or possesses only a single epitope for antibody binding, a competitive format is employed. In this approach, a labeled antigen competes with the unlabeled sample antigen for binding to a limited number of immobilized enzyme-conjugated primary antibody. Each of these ELISA formats can be utilized for both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Figure 2. Four Types of ELISA

3. What Factors Could Affect ELISA Results?

ELISA is a multi-step analytical process. The accuracy and reproducibility of an ELISA result are governed by a complex interplay of factors across the entire workflow. Failure to control these can lead to false positives, false negatives, or inaccurate quantification. There are three main reasons for the erroneous results of ELISA:

3.1 Specimen Factors

Extensive specimens that can be used for ELISA assays, including body fluids (such as serum, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid), secretions (saliva), and excreta (such as urine, feces), to determine an antibody or antigen component. Some can be measured directly (e.g., serum, urine); others require pretreatment (e.g., feces, certain secretions).

Serum is the most commonly used specimen in an ELISA assay. Plasma is generally regarded as the same specimen as serum. Specimens-caused false positive and false negative results are mainly caused by interfering substances, which are divided into endogenous substances and exogenous substances:

| Category |

Specific Factors |

Description / Impact |

| Endogenous Interfering Substances |

General Situation |

~40% of human serum contains nonspecific interferents, affecting results

to varying degrees.

|

| Rheumatoid Factor (RF) |

IgM/IgG-type RF binds to the Fc segment of antibodies in the ELISA

system, leading to false positives.

|

| Complement |

Antibody allostery exposes the C1q binding site on the Fc segment; C1q

can bridge the solidoid primary antibody and enzyme-labeled secondary

antibody, causing false positives.

|

| Heterophilic Antibodies |

Natural heterophilic antibodies in human serum that bind to rodent

(e.g., murine) Igs can bridge the primary and secondary antibodies,

causing false positives.

|

| Autoantibodies to Target Antigens |

e.g., anti-thyroglobulin, anti-insulin. Can form complexes with the

target antigen, interfering with assay results.

|

| Iatrogenically Induced Anti-Mouse Ig Antibodies |

Produced due to clinical use of murine monoclonal antibodies (e.g.,

mouse-derived CD3, radio-isotope labeling of mouse-derived antibody

imaging diagnosis, targeted therapy) or rodent bites. Anti-mouse Ig (s)

antibodies can cause false positives.

|

| Cross-Reactive Substances |

e.g., digoxin-like, AFP-like substances. Minimal impact with polyclonal

antibodies. May cause false positives with monoclonal antibodies if the

cross-reactive epitope matches the monoclonal antibody's target.

|

| Other Substances |

Excessive serum lipids, bilirubin, hemoglobin, and high blood viscosity

all interfere with results.

|

| Exogenous Interfering Factors |

Primary Cause |

Improper specimen collection or storage. |

| Specimen Hemolysis |

Releases hemoglobin with peroxidase activity, causing non-specific

coloration in HRP-based ELISA. Avoid hemolysis during collection.

|

| Bacterial Contamination |

Bacteria may contain endogenous HRP, causing non-specific coloration.

|

| Improper Specimen Storage |

Prolonged Refrigeration: Can cause polymerization of serum IgG or

dimerization of AFP, leading to high background or false positives.

Prolonged Storage (>1 day): Antigen/antibody immunoreactivity may

weaken, causing false negatives.

Recommended Storage: Fresh testing is best. For use within 5 days:

2-8°C; up to 1 month: -20°C; up to 2 months: -80°C. After

thawing, mix gently but thoroughly. Avoid repeated freezing and thawing.

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles can cause protein aggregation or

fragmentation, altering immunoreactivity.

|

| Incomplete Agglutination |

Residual fibrinogen can form visible clots during assay, potentially

causing false positives. Ensure complete clotting before centrifugation

or use serum separator tubes/clot activators.

|

| Effects of Tube Additives |

Anticoagulants (e.g., heparin), enzyme inhibitors (e.g., NaN3 inhibits

HRP), and rapid serum separator gels may interfere ELISA determination.

|

In all, when false positives/negatives occur, analyze specimen factors first before considering reagent or operational factors, and take corresponding measures to eliminate interference.

3.2 Reagent Factors (Key Considerations for ELISA Kit Selection)

Currently, the highly variable quality of commercially available ELISA kits can significantly impact the accuracy of test results, making the selection of an appropriate kit crucial. Key considerations for selection should include the kit's intended uses, such as its detection range, applicable sample types, species specificity, and quality control parameters (e.g., specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility); as well as customer verification aspects like supporting literature references, alongside practical factors such as the kit's expiration date.

The article 'How to Choose the Right ELISA Kit for Your Research?' is helpful for researchers who are struggling to select an appropriate kit.

| Consideration |

Key Points & Explanations |

| Detection Range |

The range of the standard curve. Ensure the target sample concentration falls within this range.

The "Hook Effect": In one-step sandwich ELISAs, extremely high antigen concentrations can saturate both capture and detection antibodies independently, preventing sandwich complex formation and causing a falsely low signal—a dangerous pitfall in diagnostics for markers like procalcitonin.

Perform a preliminary test for highly concentrated samples to determine optimal dilution. Reference values from databases (NCBI, UniProt) can be consulted.

|

| Application Species |

ELISA kits for different species are generally not universal unless specified in the instructions. |

| Test Sample Type |

Common types: serum, plasma (note anticoagulant), cell supernatant, cell lysate. Strictly follow the kit instructions for sample processing and diluent selection. Do not mix diluents for different samples. |

| Specificity |

Determined by the key component—the antibody pair. The specificity and affinity of the antibody pair (in sandwich ELISA) are paramount. Cross-reactivity or low affinity leads to poor sensitivity and specificity. |

| Sensitivity |

Reflects the minimum detectable amount of the analyte. Choose based on the expected analyte level in your sample. High-sensitivity kits are available for very low abundance targets. |

| Repeatability (Precision) |

Essential for scientific experiments. Typically, the intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) should be controlled within 15%. For example, CUSABIO kits often have intra-assay CV < 8% and inter-assay CV < 10%. |

| Literature Citations |

Citations, particularly in high-quality SCI articles, are a strong indicator of product recognition and reliability, providing a valuable reference for users. (CUSABIO ELISA kits have over 27000 citations). |

| Shelf Life / Expiry Date |

Kits typically have a shelf life of six months. Consider validity when planning experiments. |

In a word, ELISA kit quality varies significantly on the market and critically impacts the accuracy of results. Selection requires a comprehensive evaluation of the above factors.

3.3 Operational Factors (Key Points for ELISA Experimentation)

ELISA technology is highly regarded in biological research and widely used in clinical testing due to its high sensitivity and specificity. However, beginners may significantly impact the final experimental outcomes—such as encountering blank wells, weak coloration, low sensitivity, uneven plates, absent gradients, or high background—if they do not carefully adhere to all steps during experimental operation. Specific problems and solutions that may arise, you can refer to: Do you often trouble in these problems of ELISA?

Therefore, it is crucial to strictly follow the ELISA protocol and pay close attention to the following issues:

| Operational Stage |

Specific Steps / Precautions |

| General Principle |

Strictly adhere to the protocol provided with the ELISA kit. |

| Reagent Preparation |

a. Equilibration: Allow all kit components (pre-coated plate, reagents) to equilibrate to room temperature for >30 min.

b. Mixing: Mix all reagents thoroughly before use to ensure uniformity and accuracy.

c. Wash Buffer: Concentrated solution must be diluted beforehand. Maintain pH between 7.2 and 7.4.

d. Antibody Dilution: Dilute detection antibodies and enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies to working concentration with the specified diluent.

e. Lot & Validity: Do not mix reagents from different lots. Check the expiration date of all components. |

| Sample Addition |

a. Batch Processing: If testing many samples, process in batches.

b. Pre-dilution: Pre-dilute samples as required by the protocol using the correct diluent.

c. Timing: Control the sample addition time to prevent errors from prolonged processing.

d. Technique: Add sample vertically to the bottom of the well; avoid touching the well walls.

e. Prevent Contamination: Use a new pipette tip for each sample to prevent cross-contamination. |

| Incubation & Washing |

a. Incubation Conditions: Follow the specified incubation time and temperature precisely.

b. Uniform Incubation: Incubate in a water bath or humidified chamber to avoid "edge effects."

c. Washing Details: Pay attention to the number of washes, wash buffer volume, soak time, and wash vigor.

d. Manual Washing: Hold the plate vertically; avoid splashing/cross-contamination. Do not shake too vigorously to prevent dislodging antigen-antibody complexes.

e. Automated Washer: Regularly check that dispensing needles are not clogged. |

| Color Development |

Protect from light. Incubate at 37°C or room temperature for 15-30 minutes as specified. |

| Reading & Data Analysis |

a. Stopping: When adding stop solution, avoid creating bubbles in the wells.

b. Reading Time: Complete the plate reading within 5 minutes after stopping the reaction.

c. Instrument Warm-up: Pre-warm the microplate reader for 15-30 minutes.

d. Curve Fitting: Common methods: four- or five-parameter logistic (4PL/5PL) fit. Choose based on the correlation coefficient (R²) of the standard curve (typically should be >0.99).

e. Plate Reader Performance: Uncalibrated readers with failing lamps or dirty optics introduce inaccuracy. Regular calibration and maintenance are non-negotiable. |

| Reagent Storage |

a. Proteins/Antibodies: For short-term storage, keep at -20°C.

b. Substrate/Wash Buffer: Store at 2-8°C. |

Conclusion

In summary, ELISA stands as a powerful and versatile pillar of modern bioanalysis; however, its successful application requires precision and vigilance. As explored, the journey from sample to reliable result is guided by a clear strategic choice of the appropriate format—direct, indirect, sandwich, or competitive ELISA—each with distinct advantages for specific analytical challenges. The integrity of the final data is exquisitely dependent on mastering three interconnected domains: the quality of the specimen, the performance characteristics of the reagents selected, and the meticulousness of the operational execution.

Ultimately, ELISA is far more than a procedural recipe; it is a synthesis of sound biochemical principles, rigorous analytical methods, and a commitment to standardization at every step. By appreciating and controlling the critical factors discussed, from kit selection and sample preparation to washing consistency and data interpretation, researchers can fully harness the power of this indispensable assay. This ensures that the findings generated are built upon a foundation of trustworthy, reproducible science, solidifying ELISA's role as a reliable workhorse for years to come.

References

[1] Hayrapetyan, H., Tran, T., Tellez-Corrales, E., Madiraju, C. (2023). Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay: Types and Applications [J]. In: Matson, R.S. (eds) ELISA. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 2612.

[2] Gan, Stephanie D. et al. Enzyme Immunoassay and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay [J]. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Volume 133, Issue 9, 1 - 3.

CUSABIO team. What Factors Could Affect ELISA Results?. https://www.cusabio.com/c-15109.html

.webp)

Comments

Leave a Comment