Recently, findings from Jiancheng Wang et al. revealed a pro-fibrotic function of nestin partially through promoting Rab11-dependent recycling of TβRI and provided a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis [1]. The protagonist nestin is a pluripotent protein well-known for its role as a neuronal stem cell marker.

Herein mainly introduces the gene, structure, expression, and related clinical studies of nestin.

1. What is Nestin?

In 1985, Hockfield and Mckay identified an antigen transiently expressed in cells at an early stage of neural development and in non-neuronal cells in the peripheral nervous system using the Rat-401 monoclonal mouse antibody [2]. This was the first description of the nestin protein.

In 1990, Lendahl et al. cloned the gene encoding the Rat-401 antigen [3]. They solely defined this antigen the class VI intermediate filament (IF) and named it nestin due to its partial homology with the other five types of intermediate filaments and several unique characteristics including a truncated N-terminal head, a long C-terminal tail, and the presence of a third intron in its gene [3].

Nestin is a class VI intermediate filament protein closely related to neurofilaments. It is involved in cytoskeleton formation, organization and maintenance of cell morphology, promotion of the depolymerization of vimentin, as well as the regulation of the spatial localization of cell organelles. Nestin is also associated with essential stem cell functions, including self-renewal, proliferation, survival, differentiation, and migration.

In some tumors, high expression of nestin is positively correlated with invasive growth, metastasis, and poor prognosis. Nestin phosphorylation has also been demonstrated to directly affect the proliferation of cancer cells [4].

2. Nestin Structure

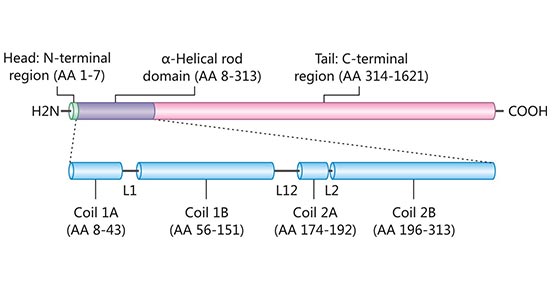

The human nestin protein contains 1621 amino acids and is divided into three regions: N-terminal head (1-7aa), α-helix rod (8-313), and C-terminal tail (314-1621aa). The α-helix rod domain is divided into three parts linked by two linkers: coli 1A and coli 1B separated by linker 1, coli 2A and coli 2B with linker L2 between them, separated from coli 1B by linker L12.

Figure 1. Domain structure of Nestin

This picture is cited from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4520630/

Like other intermediate filaments, nestin has a highly conserved 306-amino acid α-helical rod domain flanked by the C- and N-terminal domains [5][6]. The rod domain forms the core of nestin, within which helical coils are important for dimerization and consecutive filament formation.

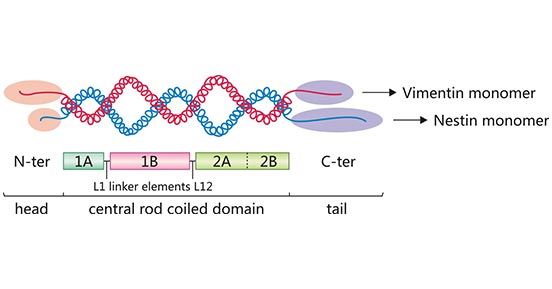

Nestin's very short N-terminal head disables its self-assembly. Consequently, nestin needs to form heteropolymeric filaments with other intermediate filament proteins such as vimentin, desmin, and α-internexin. The N-terminus is important for filament protein formation [7].

Figure 2. Nestin-vimentin dimer

The central rod domain contains hydrophobic repeats that mediate dimerization allowing two α-helices to entwine each other into a "coiled coil".

In addition, nestin's long C-tail domain stretches out from the filament structure, being accessible to post-translational modifications and protein interactions [5].

3. Nestin Gene

The human nestin gene is located on chromosome 1, 23.1q. The nestin gene contains four exons separated by three introns. Two of three introns are the same as the neurofilament, indicating the possibility that nestin and neurofilament are derived from one ancestor.

Transgenic studies revealed that the first intron contains a promoter that regulates the expression of nestin in skeletal myoblasts. There are two E-box motifs in the first intron with a helix-loop-helix structure, which is the binding site of transcription factors in skeletal muscle development.

The second intron contains two enhancers that regulate nestin expression in neural precursor cells of the central nervous system (CNS).

One is located in the 374 bp region of intron 2, which regulates the expression of nestin in the neural precursor cells of most of the neural tubes in embryos, such as thyroxine receptor, retinoic receptor, and 9-cis-retinoic receptor. A 120 bp sequence is a necessary element for this enhancer. And there are binding sites for nuclear hormone receptors and transcription factors in this 120 bp region.

The other is a region-specific enhancer that regulates the expression of nestin in embryo midbrain neural progenitor cells, which are located at the 5' end of the 120 bp sequence.

4. Nestin Expression

Nestin is localized in the cytoplasm and is mainly expressed in undifferentiated cells with the potential to divide. The expression of nestin follows a strict temporal and spatial order. During the development of the embryonic central nervous system, nestin is primarily expressed in proliferating or migrating neural stem cells or neural progenitor cells, while in adults, nestin is expressed at specific regions of the central nervous system, such as ependymal cells of the brain and spinal cord, which have the potential to differentiate into neurons. Therefore, nestin is likened to the "GPS" in the human body.

Ample studies have found that nestin is also expressed in stem/progenitor cells in various tissues, such as the non-hematopoietic fraction of the bone marrow, skeletal muscles, pancreas, hair, heart, and skin. The expression of nestin in stem cells is usually transient, that is, nestin expression stops upon these cells' differentiation. So nestin is widely used as a signature protein for stem cells.

Nestin expression is upregulated in most mitotic cells but downregulated in all cells upon differentiation. Nestin may be re-expressed by a variety of pathological conditions such as injury, neurodegenerative disorders of the brain, and the process of carcinogenesis [8][9].

The expression of the nestin gene is regulated by multiple factors, including trans-acting factors, phosphorylation of carboxy-terminal domains, and internal regulatory elements of genes. It may be the comprehensive regulation of these factors that makes the expression of nestin in the embryonic stage present its specific spatio-temporal pattern or reproduce the expression pattern in adult reactive astrocytes and tumor cells.

5. Nestin Clinical Research

Recently, nestin expression has been detected in various tumor tissues, such as brain glioma, bladder cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer. Moreover, the expression of nestin is positively correlated with tumor proliferation and metastasis. Therefore, nestin is also considered a marker of cancer stem cells (CSCs) [10].

Nestin is mainly the earliest intermediate filament precursor protein expressed in a specific stage of the embryo, and its expression is reproduced in tumor cells and reactive astrocytes. Therefore, nestin is often regarded as a marker of neural stem cells or an indicator for the diagnosis of poorly differentiated tumors, as well as one of the a rapid and sensitive diagnostic indicator of neurological diseases and injuries.It is important for the analysis of the evolution of the nervous system.

In addition, nestin expression is increased in a variety of tumor tissues, and nestin expression has been associated with several processes, including cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis. The level of nestin expression is positively correlated with the extent of malignancy of the tumor. Therefore, the expression level of nestin in tumor tissues is of great significance for evaluating the biological behavior of the tumor and the prognosis of patients [11].

CUSABIO provides a series of nestin products for scientific research, including recombinant proteins and antibodies.

| Product Categories |

Product Name |

| Recombinant proteins |

Recombinant Human Nestin (NES), partial |

| Recombinant Rat Nestin (Nes), partial |

| Recombinant Danio rerio Nestin (nes), partial |

| Recombinant Mouse Nestin (Nes), partial |

| Recombinant Mesocricetus auratus Nestin (NES), partial |

| Antibodies |

NES Monoclonal Antibody |

| NES Antibody (ELISA, IHC, IF) |

| NES Antibody (ELISA, IHC) |

| NES Antibody, HRP conjugated |

| NES Antibody, FITC conjugated |

| NES Antibody, Biotin conjugated |

References

[1] Jiancheng Wang, Xiaofan Lai, et al. Nestin promotes pulmonary fibrosis via facilitating recycling of TGF-β receptor I [J]. Eur Respir J. 2022 May 5;59(5):2003721.

[2] Hockfield S and McKay RD. Identification of major cell classes in the developing mammalian nervous system [J]. J Neurosci. 1985;5:3310–28.

[3] Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, Mckay RDG.CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein [J]. Cell, 1990,60:585-595.

[4] Matsuda Y, Ishiwata T, et al. Nestin phosphorylation at threonines 315 and 1299 correlates with proliferation and metastasis of human pancreatic cancer [J]. Cancer Sci. 108:354–361. 2017.

[5] Michalczyk K and Ziman M. Nestin structure and predicted function in cellular cytoskeletal organisation [J]. Histol Histopathol. 20:665–671. 2005.

[6] P M Steinert and D R Roop. Molecular and cellular biology of intermediate filament [J]. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:593-625.

[7] N. J. Buchkovich, W. M. Henne, et al. Essential N-Terminal insertion motif anchors the ESCRT-III filament during MVB vesicle formation [J]. Developmental Cell, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 201–214, 2013.

[8] Lu G, Kwong WH, et al. Bcl2, bax, and nestin in the brains of patients with neurodegeneration and those of normal aging [J]. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;27:167-174.

[9] Frisen J, Johansson CB, et al. Rapid, widespread, and longlasting induction of nestin contributes to the generation of glial scar tissue after CNS injury [J]. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:453-464.

[10] Jakub Neradil and Renata Veselska. Nestin as a marker of cancer stem cells [J]. Cancer Sci, 2015,106:803–811.

[11] Kleeberger W, Bova GS, Nielsen ME, et al. Roles for the stem cell associated intermediate filament Nestin in prostate cancer migration and metastasis [J]. Cancer Res, 2007,67(19):9199-206.

CUSABIO team. Nestin, the GPS in Human Body. https://www.cusabio.com/c-19850.html

Comments

Leave a Comment