The mitochondria are double-membrane-bound organelles found in most eukaryotic organisms and are the main energizing organelles of cells. The most prominent roles of mitochondria are to produce the energy currency of the cell, ATP (i.e., phosphorylation of ADP), through respiration, and to regulate cellular metabolism. The central set of reactions involved in ATP production are collectively known as the citric acid cycle, or the Krebs cycle.

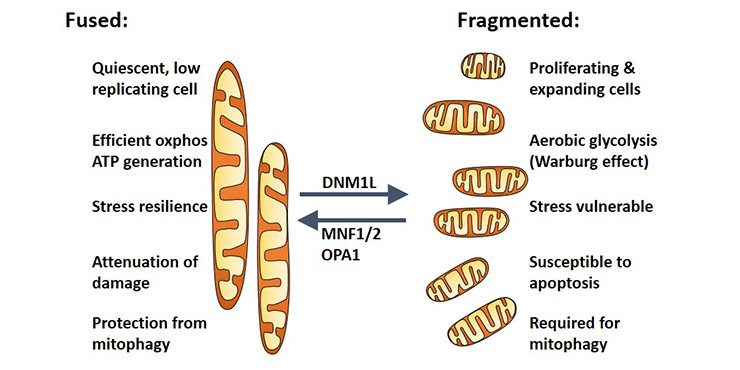

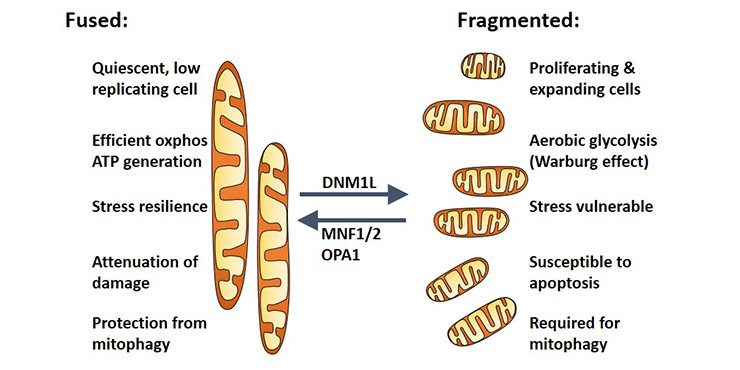

They are also involved in the storage and regulation of calcium ions, cell proliferation, cell differentiation and cell death. Mitochondria constitute a mitochondrial network through the dynamic equilibrium of division and fusion (as shown in Figure 1), which is also known as mitochondrial dynamics, which is an important way to regulate mitochondrial quality [1]. It has also been a hotspot and difficulty in mitochondria-related research.

Figure 1. The function of mitochondrial network

OMA1, is a zinc ion metalloproteinase encoded by the OMA1 gene and independent of ATP. It is also a redox-dependent protein with multiple transmembrane domains and zinc finger binding motifs located in the mitochondrial inner membrane. At present, it is quite consistent that OMA1 can control the dynamic balance of mitochondrial division and fusion by regulating the hydrolysis of intimal protein OPA1 protein [2].

OPA1 is a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein with similarity to dynamin-related GTPases encoded by OPA1 gene. OPA1 is a mitochondrial in vivo priming protein and is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. OPA1 mainly focuses on the regulation of mitochondrial stability and energy output.

Although OMA1 has been testified to hydrate OPA1 as an enzyme, the mechanism still isn’t clear. Further clarifying the mechanism of action of mitochondrial protease OMA1 is of great significance for the pathogenesis of many diseases. Here, we detail mitochondrial protease OMA1 from four aspects: structure, function, regulation and related diseases.

1. The structure of OMA1

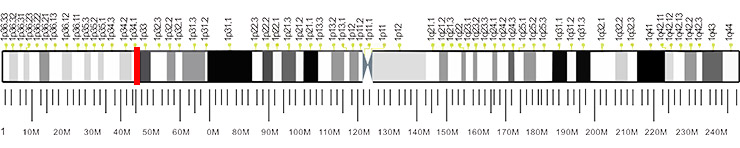

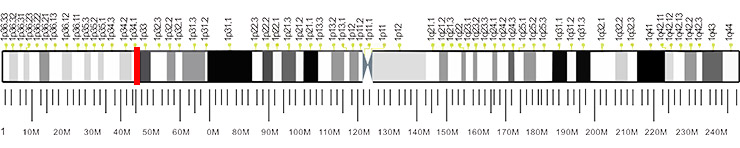

The gene OMA1 encodes a metalloprotease, a founding member of a conserved family of membrane-embedded metallopeptidases in mitochondria. The human gene has 9 exons and locates at chromosome band 1p32.2-p32.1.

Figure 2. The location of OMA1 gene

The human endopeptidase OMA1 consists of 524 amino acids, and is synthesized as a pre-pro-protein of 60 kDa that undergoes proteolytic processing upon import into mitochondria to generate a mature form of 40 kDa. Its theoretical pI of mature OMA1 protein is 8.44 [3]. This protein is called OMA1 because it has overlapping activity with m-AAA protease [4].

The human ortholog of OMA1 is MPRP-1, which was originally thought to be the endoplasmic reticulum. And it doesn’t receive attention until 2003. In the studies of demonstrating localization of OMA1, they also revealed that mammalian homologs have an extended amino terminus of 170 amino acids in length at the N-terminus, which may have an impact on the topology of higher organisms [5]. From then on, many researchers suggest that the topology of this multi-transmembrane protein must be biochemically established, and the catalytic sites must be localized to further understand its regulation.

2. The Function of OMA1

There are two AAA proteases on the inner mitochondrial membrane, i-AAA and m-AAA protease.

The catalytic domain of i-AAA protease faces the membrane gap, while the active center of m-AAA is on the mitochondrial matrix side. As mentioned before, the mature OMA1 is 40 kDa. It has been proposed that is a stress-sensitive pro-protein that undergoes autocatalytic cleavage of a C-terminal subunit peptide upon stress stimuli to generate the active form of OMA1 that is ultimately responsible for OPA1 processing [6] [7]. All these findings indicate that OMA1 is a key sensor for a plethora of mitochondrial stress event. Moreover, a large number of studies have confirmed that OMA1 can degrade mammalian inner mitochondrial membrane fusion protein OPA1 when mitochondria lose membrane potential or ATP. This inducible proteolysis is the major regulatory mechanism of proteolytic inactivation of OPA1 [8] [9].

In addition, studies have shown that OPA1 has a barrier to cleavage at S1 site without changes of morphology of mitochondria under the condition of OMA1 deletion. But mitochondria are fragmented staying with OPA1 cleavage by OMA1 under the stress stimulation. OPA1 (note: the S1 mentioned here is the cleavage site of OPA1 mRNA, which will be described in detail later in the section of regulated mechanism of OMA1/OPA1). Besides, one study have showed that OMA1 deficient mice survives with diet-induced obesity. And its body's heat production is abnormal, which indicates that OMA1 plays an important role in the shearing of OPA1 while maintaining metabolic balance [10].

3. The Regulated Mechanism of OPA1-OMA1

OPA1 plays a role in many cellular activities, including mitochondrial mites, inhibition of apoptosis, maintenance of mtDNA integrity, and oxidative phosphorylation in mammalian. OPA1 is alternatively spliced, giving rise to eight variants that are expressed in a variety of patterns depending on the tissue. OPA1 pre-mRNA is alternatively spliced at exons 4, 4b and 5b, producing eight tissue-specific mRNAs encoding OPA1, and these different forms of OPA1 splices have different functions.

These mRNA-encoded polypeptides contain an S1 cleavage site in addition to the mitochondrial matrix protease MPP cleavage site (removed mitochondrial leader sequence), and some polypeptides contain an S2 cleavage site at the C-terminus. The cleavage of the S1 and S2 sites occurs in the sequence of the peptide encoded by exon 5 or 5b. Then, OPA1 loses the transmembrane domain. Theoretically, any mRNA can be translated to produce a long OPA1 (L-OPA1, only cut at the MPP site) and one or more short OPA1 (S-OPA1, cut at the Sl or S2 site) [11].

Accumulating studies showed that inner mitochondrial membrane protease OMA1 and i-AAA protease YMElL cleave OPA1 at S1 and S2 sites, respectively. L-OPA1 can be cleaved by different inducing proteases. L-OPA1 is localized on the inner mitochondrial membrane, and S-OPA1 is located in the mitochondrial membrane space. The formation of L-OPA1 can be induced by several stress conditions, such as mitochondrial membrane potential decrease, ATP deficiency, apoptosis, etc. This process is very fast and make OPA1 inactive completely.

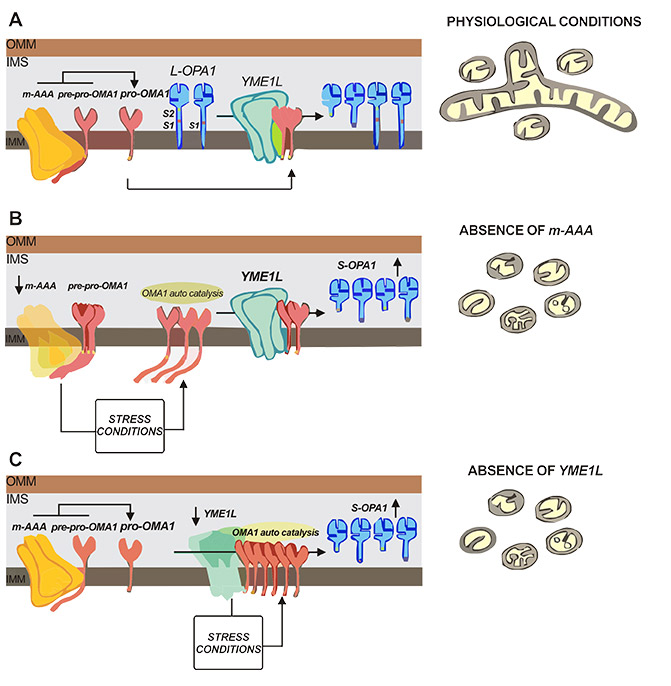

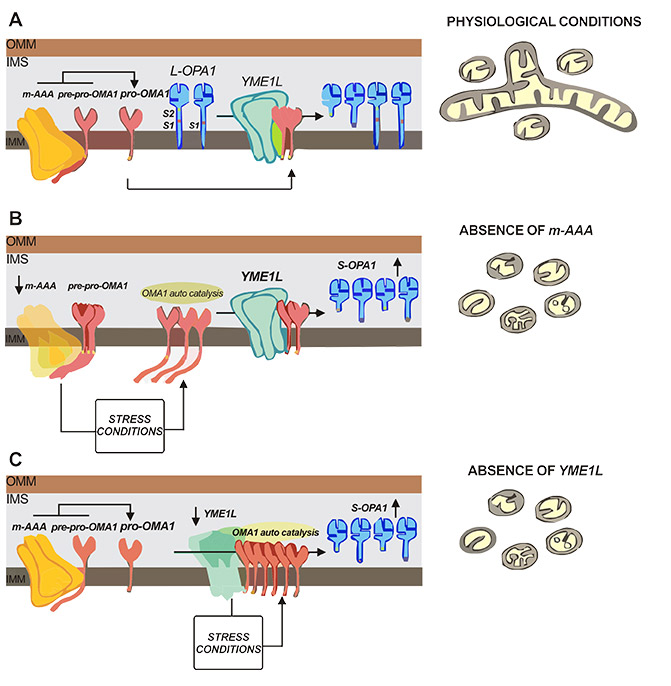

As shown in Figure 3A, under normal physiological conditions, the m-AAA protease AFG3L2 interacts with pre-pro-OMA1 and cleaves to produce pro-OMA1. The amount of pro-OMA1 can be further regulated by i-AAA protease YME1L1 activity to avoid accumulation thereof. In addition, OMA1 and YME1L1 can further cut OPA1 (at the S1 and S2 sites, respectively) to ensure the balance between L-OPA1 and S-OPA1. The yellow rectangle of the OMA1 transmembrane domain represents the leucine extension that stops m-AAA trimming.

In contrast, Figure 3B shows the absence of AFG3L2 (m-AAA), where the conversion efficiency of pre-pro-OMA1 to pro OMA1 is minimal, causing extensive organelle damage, including assembly defects in respiratory complexes, ROS production, ATP depletion, and preintimal inhibition of stress [12]. These stress responses activate other protease-regulated emergency pathways to activate downstream effects of OMA1 and mitochondrial rupture.

Fig. 3C shows the case where YME1L1 is deleted, and this case and the resulting accumulation of pro-OMA1 is the same as absence of AFG3L. It enhances its autocatalytic activity and induces mitochondrial cleavage again. Given the critical role of OMA1 in mitochondrial fusion-fission homeostasis, it is conceivable that multiple alternative effectors are required to maintain efficient fine-tuning of this key stress sensor protein, including AFG3L2, YME1L1 and OMA1 itself, as well as mitochondrial membrane potential (△φ) [13].

Figure 3. The possible mechanism of OMA1/OPA1

4. OMA1 and Diseases

As mentioned before, currently recognized role of OMA1 is to hydrolyze OPA1 protein. OPA1 is a mitochondrial in vivo priming protein that plays a role in many cellular activities, such as mitochondrial raft construction, apoptosis inhibition and maintenance of mtDNA integrity. Once stimulated by stress, activation of protease OMA1 over-hydrolyzes OPA1, and then promotes mitochondrial rupture. If it persists, it will cause cell death and tissue degeneration in vivo. These events in turn triggers a series of diseases such as autosomal optic atrophy (DOA), Barth syndrome, neurodegenerative diseases and cancer [14] [15]. Here, we focus on neurodegenerative diseases and cancer.

4.1 OMA1 and Neurodegeneration

Anne Korwitz [16] et al. used a losing vasopressin membrane scaffold to establish a mouse model of neurodegeneration disease. In this model, the authors demonstrated that hydrolysis of OPA1 by OMA1 under stress response promotes neuronal death and neuro-inflammatory responses.

Moreover, deletion of OMA1 can delay neuronal loss and prolong the lifespan of model mice and is also accompanied with the accumulation of L-OPA1. L-OPA1stabilizes the mitochondrial genome, but doesn’t maintain mitochondrial morphology and respiratory chain complex assembly status in statin depleted neurons. Therefore, L-OPA1 can promote neuronal survival independently of the scorpion shape. This conclusion was also confirmed in the absence of an inhibin membrane scaffold.

4.2 OMA1 and Cancer

There is a "Warburg effect" in cancer cells. So-called Waberg effect refers to the phenomenon of tumor cell's increased dependence on the glycolytic pathway which promotes cell proliferation and tumor growth very rapidly. Because the metabolic is different between tumors and normal adult tissues, they mainly produce capacity through glycolysis and produce large amounts of lactic acid. This metabolic property makes tumor cells consume much faster than normal cells [17]. In cancer cells dominated by the Waberg effect, mitochondrial mites are reduced [18], while OPA1 is also reduced, but OMA1 is increased.

In addition, Marcel V. Alavi presents a model for mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release by connecting the proteins OMA1 and OPA1 with prohibitin and p53 in the context of BAX and BAK1 dependent cell death. At the center of this model is the mitochondrial inner membrane protease OMA1, which becomes activated in a challenging tumor environment and which represents a bona fide drug target for novel, personalized cancer therapies.

References

[1] Marcel V. Alavi. Targeted OMA1 therapies for cancer [J]. Int J Cancer. 2019 Feb 4.

[2] Pedro M. Quirós, Andrew J. Ramsay, et al. New roles for OMA1 metalloprotease from mitochondrial proteostasis to metabolic homeostasis [J]. Adipocyte. 2013, 2:1, 7–11.

[3] Kozlowski LP. IPC - Isoelectric Point Calculator [J]. Biology Direct. 2016, 11 (1): 55.

[4] Kaser, M., Kambacheld, M., et al. Oma1, a novel membrane-bound metallopeptidase in mitochondria with activities overlapping with the m-AAA protease [J]. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 46414–46423.

[5] Bao, Y.C., Tsuruga, H., et al. Identification of a human cDNA sequence which encodes a novel membrane-associated protein containing a zinc metalloprotease motif [J]. DNA Res. 2003, 10, 123-128.

[6] Baker,M. J., Lampe, P. A., et al. Stress-induced OMA1 activation and autocatalytic turnover regulate OPA1-dependent mitochondrial dynamics [J]. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 578-593.

[7] Head, B., Griparic, L., et al. Inducible proteolytic inactivation of OPA1 mediated by the OMA1 protease in mammalian cells [J]. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 959-966.

[8] Ehses S, Raschke I, et al. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1 [J]. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2009, 187 (7): 1023–36.

[9] Korwitz A, Merkwirth C, et al. Loss of OMA1 delays neurodegeneration by preventing stress-induced OPA1 processing in mitochondria [J]. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2016, 212 (2): 157–66.

[10] McBride H, Soubannier V. Mitochondrial function: OMA1 and OPA1, the grandmastem of mitochondrial health [J]. Current biology. 2010, 20 (6):274-276.

[11] Wang JK, Wu HF, et al. Postconditioning with sevoflu-lane protects against focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury involving mitochondrial A7rP-dependent potassium channel and mitochondrial permeability transition pore [J]. Neurological research. 2015, 37(1):77—83.

[12] Maltecca, F., Aghaie, A., et al. The mitochondrial protease AFG3L2 is essential for axonal development [J]. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 2827-2836.

[13] Francesco Consolato1, Francesca Maltecca1. m-AAA and i-AAA complexes coordinate to regulate OMA1, the stress-activated supervisor of mitochondrial dynamics [J]. Journal of Cell Science. 2018, 131, jcs213546.

[14] Hoppins S, Lackner L, et al. The machines that divide and fuse mitochondria [J]. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007, 76:751-780.

[15] Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals [J]. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006, 22:79 ~99.

[16] Anne Korwitz, Carsten Merkwirth, et al. Loss of OMA1 delays neurodegeneration by preventing stress-induced OPA1 processing in mitochondria [J]. J Cell Biol. 2016, 212(2): 157–166.

[17] Esen E, Chen J, et al. WNT-LRP5 signaling induces Warburg effect through mTORC2 activation during osteoblast differentiation [J]. Cell Metab. 2013, 17:745-755.

[18] Plecita-Hlavata L, Jezek P. Integration of superoxide formation and cristae morphology for mitochondrial redox signaling [J]. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016, 80:31-50.

CUSABIO team. OMA1-A Potential Cancer Therapy Target. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20960.html

Comments

Leave a Comment