Human has been constantly struggling with various diseases from the birth. Human history documented several brutal, disastrous, and deadly diseases, such as smallpox, bubonic plague, cholera, and influenza. They broke out across international borders and caused pandemics in human history. Smallpox, in particular, has resulted in 300 to 500 million deaths throughout history. Recently-emerged COVID-19 has caused more than 100 million infections and more than 2 million deaths as of Jan. 26, 2021.

Many viral infections are contagious and can be transmitted from person to person in multiple ways. Although biomedical science and technology have developed rapidly, humans still can not completely conquer tiny viruses. Actually, the best defense against viruses is to block the infection in its tracks. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the mechanism of viral invasion and develop the corresponding treatments. Antiviral therapies have long focused on developing antiviral drugs that treat viral infections by either clearing out the viral particles or inhibiting viral replication within the human body. However, the effects of antiviral drugs are far from satisfying due to the large differential selectivity of antiviral drugs to the virus and strong adverse effects. With the unremitting efforts, experts have developed many effective and fewer side effects of antiviral therapies, neutralizing antibody (NAb) is one of the dazzling.

In this article, we will introduce neutralizing antibodies from the following aspects: definition, work mechanism, differences between neutralizing antibodies and binding antibodies, detection methods, applications, and mechanisms of viruses evasion from neutralizing antibodies.

1. What Are Neutralizing Antibodies?

Neutralizing antibodies are a subset of particular antibodies that bind to viruses and eliminate viral infectivity. Upon stimulation by viral infections or vaccinations, neutralizing antibodies are inducibly and naturally produced by B lymphocytes. Neutralizing antibodies can be both sufficient and necessary for protection against viral infections, although they sometimes function in cooperate with cellular immunity.

2. How Does Neutralizing Antibodies Work?

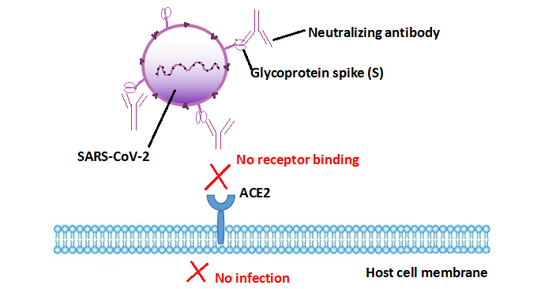

Neutralizing antibodies bind specifically to the viral surface antigen that initiates cell infection, leading to neutralizing antibody-coated virus can not interact with the receptor on host cells thus blocking the infection. For instance, SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receptor via its spike (S) glycoprotein for entry into target cells [1] [2]. Therefore, the S protein determines viral infectivity and transmissibility in the host. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 target the viral S protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) to block it from binding to ACE2 on host cells [2]. This process restrains the SARS-CoV-2 attachment and subsequent entry into host cells and inhibits the infection.

Figure: The mechanism that neutralizing antibodies blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection

3. What Are the Differences between Neutralizing Antibodies and Binding Antibodies?

Antibodies are induced against most of the viral proteins, but not all antibodies possess the neutralizing ability. Non-neutralizing antibodies are normally called binding antibodies, which bind to viral particles at the epitope that is not responsible for cell infection, thus not neutralizing the viral infectivity. Different binding epitopes on the antigen lead to distinct effects. Binding antibodies flag these virions for the immune system, so white blood cells can locate and destroy them. Whereas, neutralizing antibodies functions to directly disable the biological effects of the virus without the aid of immune cells.

4. Methods for Detecting Neutralizing Antibodies

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit is a preferred tool for researchers to qualitatively or semi-quantitatively analyze neutralizing antibodies of a certain virus. Here, we take the SARS-CoV-2 as an example. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody ELISA kit enables to qualitatively or semi-quantitatively detect the total neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S protein in human serum and plasma. However, assessing the antibody's virus-neutralizing ability depends on cell-based or non-cell-based neutralization assays.

Neutralizing antibodies to a biotherapeutic protein are generally detected in two types of assays: cell-based assays (CBA) and competitive ligand-binding assays (CLBA). CBA closely mimics the mechanism by which the neutralizing antibodies exert their effect within a living biological system and is often the preferred method to detect the presence of neutralizing antibodies [3]. It is difficult to standardize and poorly adapted to high-throughput analysis and display low assay robustness, drug tolerance, and sensitivity.

CLBA compensates for these above limitations of CBA and may be a valuable alternative to a CBA. CLBA is comparable even superior to CBA in many aspects, such as sensitivity, drug tolerance, and precision [4]. The CLBA is based on the electrochemiluminescent immunoassay (ECLIA) mechanism and the drug's mechanism of action (MoA). The decreased antibody binding and luciferase relative light units (RLU) signal indicates the presence of neutralizing antibodies to the biotherapeutic agent and also allows for semi-quantitative measurement of neutralizing antibodies.

Chee Wah Tan et al. reported a SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test (sVNT) that measures total immunodominant neutralizing antibodies targeting the viral S-RBD in an isotype- and species-independent manner. This simple and rapid test is based on antibody-mediated blockage of the ACE2-RBD interaction. Validated in two cohorts of patients with COVID-19 in two different countries, the test achieved 99.93% specificity and 95-100% sensitivity and differentiated antibody responses to several human coronaviruses. No requirement for biosafety level 3 containment makes sVNT broadly accessible to the wider community for both research and clinical applications [5].

5. The Applications of Neutralizing Antibodies

Neutralizing antibodies are significantly valuable in the prevention and therapy of virus infections. They can help identify neutralizing epitopes of vaccine utility and understand the mechanism of potent and broad cross-neutralization [6]. Neutralizing antibodies (including monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies) can target specific epitopes via their variable domains through a precise neutralization mechanism and hold enormous potential to be designed into pharmaceutical products [7]. Therapeutic neutralizing antibodies can be passively injected into individuals before or after viral infection to prevent or treat disease. Many factors, including neutralizing antibody titer, total amount, specificity, and half-life determine the efficacy of therapeutic neutralizing antibodies. At present, neutralizing antibodies with high specificity, strong affinity to target proteins, and low toxicity have been used to treat viral infections caused by the Ebola virus, influenza virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and respiratory syncytial virus.

For biopharmaceuticals, neutralizing antibodies are a subset of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) that bind to the active site of the drug, thus attenuating or eliminating the associated biological activity [8]. Neutralizing antibodies within the biological drugs not only inhibit the activity but also compromise the safety of biopharmaceuticals [12]. So assessing immunogenicity can provide a deeper insight into the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceutical candidates. Any large molecule establishment needs rigorous evaluation of immunogenicity.

Neutralizing antibodies possess the potential to block the virus from infecting the targeted cells, and monoclonal antibodies have advantages in determining the mechanism of action (MoA) and being easy for mass production, allowing neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to dominate in the research area of anti-virus medicine.

6. Mechanisms of Virus Evasion from Host Neutralizing Antibodies

Viral clearance largely depends on the rapid induction of neutralizing antibodies in the early stage of infection. However, viruses evolve several mechanisms as time accumulates to elude host neutralizing antibodies to maintain their persistence in host cells. Here list three mechanisms that viruses escape from host neutralization.

6.1 Through Binding to Lipoproteins

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) combines with very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs) and low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), shielding epitopes on viral surface glycoproteins thus protecting neutralizing antibodies [9]. And LDL- and VLDL-coated HCV is internalized by the LDL receptor (LDLR) into human cells, resulting in infection. HCV binding to high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) accelerates viral cell entry, thus reducing the time of HCV exposure to neutralizing antibodies [9].

6.2 Through Glycosylation of the Envelope Glycoproteins

The envelope glycoproteins of HCV are highly glycosylated and consist of several N-linked glycans in E1 and E2. These glycans bound to viral envelope proteins attenuate the viral immunogenicity by masking key epitopes, thus keeping HCV from neutralization [9].

6.3 Mutations in Viral Surface Proteins That Involve in Cell Infection

High genetic variation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) results from the error-prone feature of reverse transcriptase (RT) and high rates of viral replication. Mutations in viral envelope (Env) proteins alter the Env antigenicity, leading to an increase in neutralization resistance of the variant virus [10]. The head domain of HA2 of influenza A virus (IAV) contains epitopes for most neutralizing antibodies elicited by virus infection or vaccination, so its mutations contribute to evasion from antibody neutralization [11]. The mutations in S-RBD of SARS-CoV-2 may produce new variants, which may escape from the neutralization effects of existing neutralizing antibodies.

Based on the theory that neutralizing antibodies block viral toxic effects before the virus enters cells, corresponding neutralizing antibodies present in the body before exposure to the virus can effectively prevent infection. Vaccine development often targets to elicit a neutralizing antibody response, which commonly correlates with protection from infection. Therefore, successful vaccines against viruses induce the production of neutralizing antibodies. Existing vaccines, including measles, polio, hepatitis B, and hepatitis A, cause people to produce neutralizing antibodies to protect against the corresponding virus. Highly anticipated COVID-19 vaccines also depend on vaccine-producing neutralizing antibodies to achieve protective effects.

Antibody-mediated neutralization of viruses is the direct inhibition of viral infectivity. The elicitation of a neutralizing-antibody response is associated with protection for many vaccines and contributes to long-term protection against many viral infections. Antibodies specific for RBD and ACE2 binding epitopes play an essential role in the development of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies, so the mutations in the RBD region may generate new variant strains that would escape from the known neutralization effects of the RBD antibodies. Therefore, developing a combination of neutralizing antibodies against different epitopes of RBD or producing antibodies with high neutralizing activity against conserved epitopes will be effective strategies to prevent immune evasion caused by virus mutations.

We are now one year into the COVID-19 outbreak, and COVID-19 remains robust globally. However, we do not have any specific drugs or an effective vaccine to treat or control SARS-CoV-2. So it is urgent to develop and research a reliable and potent serological or antibody test to detect neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. This test will determine not only the infection rate, herd immunity, and predicted humoral protection, but also vaccine efficacy during clinical trials and after mass vaccination [5].

References

[1]Yang, J., Petitjean, S.J.L., et al. Molecular interaction and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptor [J]. Nat Commun 11, 4541 (2020).

[2] Huang, Y., Yang, et al. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19 [J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin 41, 1141–1149 (2020).

[3] Pierre Jolicoeur and Richard L Tacey. Development and validation of cell-based assays for the detection of neutralizing antibodies to drug products: a practical approach [J]. Bioanalysis. 2012 Dec;4(24):2959-70.

[4] Yuling Wu, Ahmad Akhgar, et al. Selection of a Ligand-Binding Neutralizing Antibody Assay for Benralizumab: Comparison with an Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity (ADCC) Cell-Based Assay [J]. AAPS J. 2018 Mar 14;20(3):49.

[5] Chee Wah Tan, Wan Ni Chia, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test based on antibody-mediated blockage of ACE2-spike protein-protein interaction [J]. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Sep;38(9):1073-1078.

[6] Rajesh Ringe and Jayanta Bhattacharya. Preventive and therapeutic applications of neutralizing antibodies to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) [J]. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2013 Jul; 1(2): 67–80.

[7] Ali, M.G., Zhang, Z., et al. Recent advances in therapeutic applications of neutralizing antibodies for virus infections: an overview [J]. Immunol Res 68, 325–339 (2020).

[8] G. R. Gunn, III, D. C. F. Sealey, et al. From the bench to clinical practice: understanding the challenges and uncertainties in immunogenicity testing for biopharmaceuticals [J]. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016 May; 184(2): 137–146.

[9] Caterina Di Lorenzo, Allan G. N. Angus, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Evasion Mechanisms from Neutralizing Antibodies [J]. Viruses. 2011 Nov; 3(11): 2280–2300.

[10] Michael E. Abram,a Andrea L. et al. FerrisMutations in HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Affect the Errors Made in a Single Cycle of Viral Replication [J]. J Virol. 2014 Jul; 88(13): 7589–7601.

[11] Chai N, Swem LR, et al. Two Escape Mechanisms of Influenza A Virus to a Broadly Neutralizing Stalk-Binding Antibody [J]. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12(6): e1005702.

[12] Carlos Pineda, Gilberto Castañeda Hernández, et al. Assessing the Immunogenicity of Biopharmaceuticals [J]. BioDrugs. 2016; 30: 195–206.

CUSABIO team. Neutralizing Antibody Stands Out Among Antiviral Therapies. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21014.html

Comments

Leave a Comment