Cancer of the uterine cervix, also called cervical cancer, is among the most preventable human malignancies, yet it remains a leading cause of death among women worldwide [1] [2]. According to the data from World Health Organization, there were approximately 569,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 311,000 deaths from the disease occurred in 2018, 84% of which occur in underdeveloped countries. The estimated incidence of cervical cancer was 13 per 100,000 women, and mortality rates was 7 per 100,000 women. Although the morbidity and mortality of cervical cancer worldwide have been declining in the past 40 years, the average age of cervical cancer has been decreasing in recent years, and there is a trend of getting younger. So what is the cervical cancer? What is the cause of Cervical Cancer? Will cervical cancer appear in ourselves? And How to prevent yourself from cervical cancer?

1. What is the Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer is a type of cancer that occurs in the cells of the cervix-the lower part of the uterus that connects to the vagina (Figure 1). It is the most common gynecological malignancy. This cancer can affect the deeper tissues of their cervix and may spread to other parts of their body, often the lungs, liver, bladder, vagina, and rectum.

Figure 1. a diagram of cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is mainly divided into two types, including squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Among of them, squamous cell carcinoma begins in the thin, flat cells (squamous cells) lining the outer part of the cervix, which projects into the vagina. It is the main type of cervical cancers. Adenocarcinoma begins in the column-shaped glandular cells that line the cervical canal. Actually, less commonly, cervical cancer have features of both squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. This type of cervical cancer is also called adenosquamous carcinomas or mixed carcinomas.

2. What is the Cause of Cervical Cancer?

Generally, cervical cancer begins when healthy cells in the cervix develop changes or mutations in their DNA. The mutations tell the cells to grow and multiply out of control, and they don't die. And the accumulating abnormal cells form a tumor. Cancer cells invade nearby tissues and can break off from a tumor to metastasize elsewhere in the body.

Currently, accumulating evidence has revealed that most cervical cancer are caused by the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV), which is a group of about 100 related virus. Some of them cause a type of growth called papillomas, which are more commonly known as warts. In addition to HPV infection, there are also several other things that can increase your risk of cervical cancer, including having HIV (the virus that causes AIDS), smoking, taking birth control pills for a long time (five or more years), having given birth to three or more children and having several sexual partners. So what is HPV? And how does HPV infection cause cervical cancer?

3. What is HPV?

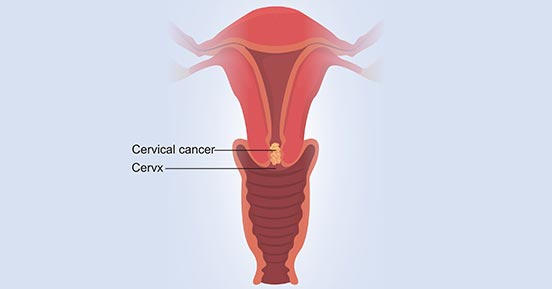

HPV encompass more than 120 different types that may infect human skin and mucosa. HPV is a relatively small, non-enveloped virus, 55 nm in diameter. The HPV gene consists of a single molecule of double-stranded, circular DNA containing approximately 7,900 bp associated with histones. All open reading frame (ORF) protein-coding sequences are restricted to one strand. The gene is functionally divided into three regions. The first is a noncoding upstream regulatory region of 400 to 1,000 bp, which has been referred to as the noncoding region, the long control region (LCR), or the upper regulatory region. The second is an early region, consisting of ORFs E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7, which are involved in viral replication and oncogenesis. The third is a late region, which encodes the L1 and L2 structural proteins for the viral capsid (Figure 2) [3] [4].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the circular HPV DNA gene

*This figure is derived from the publication on Clin. Microbiol. [4]

Among of these HPVs, Only 13–15 are found in cervical cancers and other malignancies and are called ‘high risk’ HPV (HPV-HR) [5]. HPV 16 is the most important HPV-HR-type, and HPV 18 is the second. HPV 16 and 18 are associated with two thirds of all cervical cancers. HPV-HR differs from other HPV types by oncogenic properties of two proteins E6 and E7 that may interfere with cell regulation and differentiation. In fact, uterine cervix infected with HPV is very common, especially in women in their early 20s. Most infections will clear spontaneously and only a minority will finally persist for many years and decades.

4. How does HPV Infection Cause Cervical Cancer?

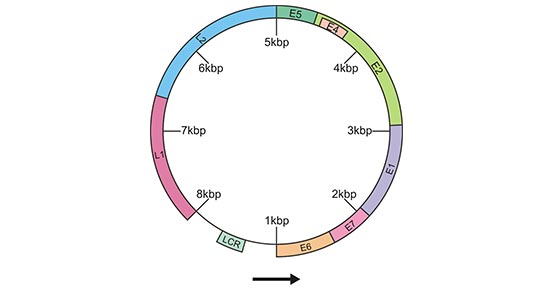

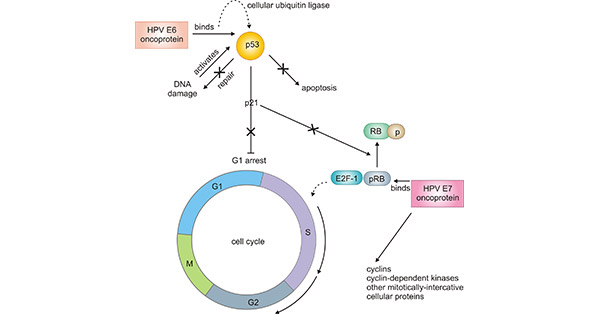

As mentioned before, being infected with a cancer-causing strain of HPV doesn't mean you'll get cervical cancer. As the figure 3 shows, your immune system eliminates the vast majority of HPV infections and prevents the virus from doing serious harm within two years. But sometimes, the virus survives for years (generally 10-30 years). The virus can lead to the conversion of normal cells on the surface of the cervix into cancerous cells.

Figure 3. How HPV damages cells

*This figure is derived from The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine 2008 illustration: Annika Rohl

Regarding of pathogenesis of oncogenic HPV, as HPVs encode only 8 to 10 proteins, they must employ host cell factors to regulate viral transcription and replication. The replication of HPV begins with host cell factors which interact with the LCR region of the HPV gene and begin transcription of the viral E6 and E7 genes. The proteins encoded by E6 and E7 gene deregulate the host cell growth cycle via binding and inactivating tumor suppressor proteins, cell cyclins, and cyclin-dependent kinases (Fig. 2) [6]. The function of the proteins encoded by E6 and E7 gene during a productive HPV infection is to bind to cellular p53 and pRB proteins, disrupt their functions, and alter cell cycle regulatory pathways, leading to cellular transformation.

Figure 4. Pathogenesis of oncogenic HPV

*This figure is derived from the publication on Clin. Microbiol. [4]

5. Latest Research Advances

Global Overview and Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer:

Due to inadequate screening protocols in many regions of the world, cervical cancer remains the fourth-most common cancer in women globally. The complete NCCN Guidelines for Cervical Cancer provide comprehensive recommendations for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of cervical cancer[7]. Geographic disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates exist, particularly in the United States, as discussed by Buskwofie et al.[8]. Hong et al. conducted a 15-year study on the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey, assessing lifetime screening rates and recommended screening rates for five major cancers[9]. Stelzle et al. aimed to investigate cervical cancer risk among women living with HIV and estimate the global cervical cancer burden associated with HIV[10].

Discovery and Application of Biomarkers:

Despite multiple efforts, the diagnosis of cervical cancer still requires the identification and development of new biomarkers. Nahand et al. summarized the potential application of miRNA as prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic biomarkers for cervical cancer[11].

Anticancer Effects of Melatonin:

Experimental evidence presented by Shafabakhsh et al. suggests that melatonin, through targeting different molecular mechanisms, serves as an adjuvant therapy with inhibitory effects on cervical cancer. This study provides the first comprehensive summary of the anticervical cancer effects of melatonin and its underlying molecular mechanisms[12].

Molecular Biology and Cervical Cancer:

Song et al.'s research, utilizing bioinformatics analysis, identified hsa_circRNA_101996 as highly expressed in cervical cancer tissues. The downregulation of miR‐8075 in cervical cancer tissues was shown to suppress the proliferation, migration, and invasion of cervical cancer cells[13].

Three-Dimensional Organoid Cultures of Cervical Cancer:

Lõhmussaar et al. described a long-term culturing protocol for cervical epithelia, generating stable 3D organoids that recapitulate the characteristics of the two tissues of origin[14].

References

[1] Campos NG, Sharma M, Clark A, et al. The health and economic impact of scaling cervical cancer prevention in 50 low- and lower-middle-income countries [J]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138 (suppl 1): 47-56.

[2] Carla J. Chibwesha, Jeffrey S. A. Cervical Cancer as a Global Concern Contributions of the Dual Epidemics of HPV and HIV [J]. JAMA. 2019, 332 (16):1558-1560.

[3] Apt, D., R. M. Watts, G. Suske, et al. High Sp1/Sp3 ratios in epithelial cells during epithelial differentiation and cellular transcription correlate with the activation of the HPV-16 promoter [J]. Virology. 1996, 224:281–291.

[4] Eileen M. Burd. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer [J]. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16(1):1.

[7] Wui-Jin Koh, Nadeem R Abu-Rustum, Sarah Bean, et al. Cervical Cancer, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology[J]. JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COMPREHENSIVE CANCER NETWORK : JNCCN, 2019.

[8]Ama Buskwofie, Gizelka David-West, Camille A Clare, A Review of Cervical Cancer: Incidence and Disparities [J]. JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, 2020.

[9]Seri Hong, Yun Yeong Lee, Jaeho Lee, et al. Trends in Cancer Screening Rates Among Korean Men and Women: Results of The Korean National Cancer Screening Survey, 2004–2018 [J]. CANCER RESEARCH AND TREATMENT , 2020.

[10]Dominik Stelzle, Luana F Tanaka, Kuan Ken Lee, et al. Estimates of The Global Burden of Cervical Cancer Associated with HIV [J]. THE LANCET. GLOBAL HEALTH, 2020.

[11]Javid Sadri Nahand, Sima Taghizadeh-Boroujeni, Mohammad Karimzadeh, et al. MicroRNAs: New Prognostic, Diagnostic, And Therapeutic Biomarkers In Cervical Cancer [J]. JOURNAL OF CELLULAR PHYSIOLOGY, 2019.

[12]Rana Shafabakhsh, Russel J Reiter, Hamed Mirzaei, et al. Melatonin: A New Inhibitor Agent For Cervical Cancer Treatment [J]. JOURNAL OF CELLULAR PHYSIOLOGY, 2019.

[13]T. Song, Aili Xu, Zongfeng Zhang, Fei Gao, et al. CircRNA Hsa_circRNA_101996 Increases Cervical Cancer Proliferation and Invasion Through Activating TPX2 Expression By Restraining MiR‐8075 [J]. JOURNAL OF CELLULAR PHYSIOLOGY, 2019.

[14]Kadi Lõhmussaar, Rurika Oka, Jose Espejo Valle-Inclan, et al. Patient-derived Organoids Model Cervical Tissue Dynamics and Viral Oncogenesis in Cervical Cancer [J]. CELL STEM CELL, 2021.

CUSABIO team. Exploring Biological Landscape of Cervical Cancer: A Comprehensive Overview for Researchers. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20996.html

Comments

Leave a Comment