ELISA is a mature detection technology, which has been widely applied since its origin in the 19th century due to its unparalleled advantages. To achieve accurate, perfect, and reproducible experimental results, experimenters need to pay attention to the factors that can affect ELISA detection results. Thus, it is crucial for researchers to be aware of these factors to obtain reliable and repeatable ELISA results.

1. What's the ELISA?

ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) is a test that helps find substances in the blood. It uses enzymes on a surface to stick to and detect the substance through a color change. The test involves adding a sample to a plate, washing it, and developing color. Instruments like pipettes, shakers, and incubators are used to do the test. ELISA can help diagnose diseases or monitor treatment progress. As a mature detection technology, ELISA is suitable for the detection of various samples, like serum, plasma, urine, saliva, etc.

2. How Many Types of ELISA?

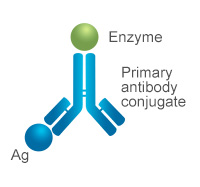

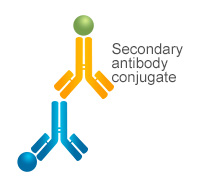

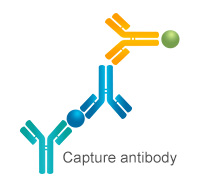

ELISA is a solid-phase heterogeneous reaction and, according to its detection principle, can mainly be divided into three types: sandwich ELISA, competitive ELISA, and indirect ELISA. The sandwich method can be further divided into double antibody sandwich and double antigen sandwich; competitive methods include direct competition and indirect competition. Based on different purposes, ELISA can also be classified into quantitative and qualitative methods. (Click to check more information about the different types of ELISA)

3. What are the Factors Influencing ELISA Detection?

3.1 Sample Sources and Pretreatment

To get accurate test results, it's important to handle and store samples properly. If a sample is hemolyzed (meaning red blood cells have broken open), it can give false-positive results because of certain substances released from the cells. You can check for hemolysis by measuring the concentration of serum Hb. In non-hemolyzed samples, the amount of free Hb should be around 4.8±3.2 mg/dL. If a sample has more than 43.5±13.9 mg/dL of free Hb, it's likely hemolyzed and should be retested to avoid wrong results [2].

For tests like LDH and ACP, even a tiny bit of hemolysis (when red blood cells break open) can give incorrect results. To avoid this, it's best to use tubes that prevent hemolysis or have anticoagulants in them. You can tell if a sample is hemolyzed by looking at it - if the serum looks bright and cherry-red, it has moderate hemolysis and should be recollected. Another problem is high lipemia, which makes the blood look milky white or cloudy. This can affect test results because the fat in the blood sticks to the tube walls. We can try to remove this by spinning the sample quickly, but that might also change the results [2].

Moreover, sample contamination or improper storage can also affect detection results. If the sample is contaminated with bacteria, non-specific color reactions will occur and interfere with the results. Plastic tubes can adsorb antigens, leading to a decrease in the antigen content in the sample and resulting in false-negative results. It is best to use vacuum blood collection tubes [2].

3.2 Operational Technique

ELISA is a highly repeatable detection technology with simple and easy-to-perform operations, but each step in the operation has a significant impact on the experimental detection effect. Correct and strict operations are the key to ensuring experimental results.

3.2.1 Sample Addition

ELISA is a microplate-based test that needs just a small amount of sample. But if the sample is not enough or sticks to the well wall, you might get a false-negative result. To avoid this, make sure you have enough sample volume and use high-precision pipettors, calibrated regularly. When adding samples, add them carefully to the bottom of the microplate without touching the walls or tube bottom to prevent bubbles or splashing. Lastly, change tips for each sample to prevent cross-contamination.

3.2.2 Incubation

ELISA test relies on the binding of antigens and antibodies, which requires a specific temperature. For most reactions, 37℃ is optimal as it yields the highest binding efficiency. It's essential to incubate the microplate at the right temperature for accurate results. However, edge effects can occur due to the microplate's design and temperature inconsistencies in constant temperature boxes. To prevent this, use water bath incubation and seal the microplate with a film to avoid evaporation or contamination. Don't shorten the incubation time, as it may lead to inaccurate results [3].

3.2.3 Plate Washing

The purpose of plate washing in ELISA is to remove non-specific components and ensure the right proportion of immune complex and test antibody (antigen). This step is crucial for accurate results. Machine washing is useful for labs with the necessary equipment to avoid contamination and improve efficiency. However, make sure the washing needle and flushing head are unobstructed to prevent clogging from residual fibrin or precipitated crystals. Adjust the water injection volume, washing time, frequency, and intensity carefully to avoid improper washing that may result in low measurement results [4].

Manual washing is an option for less equipped labs, but it's important to simulate the process repeatedly to prevent incomplete washing that can lead to "spotty" plates and affect detection results. After washing, pat the plate dry on a clean absorbent paper or towel.

3.2.4 Color Development and Interpretation

HRP is a commonly used enzyme in ELISA that catalyzes TMB to produce color. Color development is the final step of incubation, and studies show that temperature has a significant impact on results. Low temperatures lead to slower binding rates, inadequate color development, and missed low-value results. The color development time should not be too short, as low titers may not react in time, leading to false negatives. Controlling the temperature and time strictly is crucial.

An enzyme analyzer is required for ELISA, and dual-wavelength analysis is preferred to reduce interference and electrical circuit interference. This improves sample analysis accuracy at critical values, reduces omission of weak positive samples, and minimizes experimental errors [1].

3.3 Quality of ELISA Kits

There are many ELISA products on the market, making it difficult to choose high-quality products that are essential for ensuring reliable experimental results [5]. It is recommended to choose well-known brands of reagents and avoid mixing or using expired reagents. Before the experiment, it is generally necessary to take the reagents out of the refrigerator and balance them for 30-60 minutes to allow the temperature in the microplate to reach the desired temperature quickly. Ignoring this operation may lead to false-negative results for some weak positive samples.

4. Choosing Your Right ELISA Kits

Choosing the right ELISA kit involves considering essential elements like sensitivity, specificity, and stability, as these can significantly impact the quality of your results. To ensure the accuracy of your ELISA test results, it's necessary to address potential interference factors such as samples, operations, and reagents, by following strict SOP standardization protocols and undertaking meticulous quality control at every stage of the ELISA process [6] (Click to check more information about tips for choosing your right ELISA kit).

References

[1] Török, Kitti, et al. "Identification of the factors affecting the analytical results of food allergen ELISA methods." European Food Research and Technology 241 (2015): 127-136.

[2]Dong, Jinhua, and Hiroshi Ueda. "ELISA‐type assays of trace biomarkers using microfluidic methods." Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 9.5 (2017): e1457.

[3] Plested, Joyce S., Philip A. Coull, and Margaret Anne J. Gidney. "Elisa." Haemophilus influenzae Protocols (2003): 243-261.

[4] Hamblin, C., I. T. R. Barnett, and R. S. Hedger. "A new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of antibodies against foot-and-mouth disease virus I. Development and method of ELISA." Journal of immunological methods 93.1 (1986): 115-121.

[5] Clark, Michael F., Richard M. Lister, and Moshe Bar-Joseph. "ELISA techniques." Methods in enzymology. Vol. 118. Academic Press, 1986. 742-766.

[6] Diaz-Amigo, Carmen, and Bert Popping. "Accuracy of ELISA detection methods for gluten and reference materials: a realistic assessment." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 61.24 (2013): 5681-5688.

CUSABIO team. Analysis of Factors Influencing ELISA Detection. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21112.html

Comments

Leave a Comment