Generally speaking, the foundations of cancer treatment were surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. But over the past several years, immunotherapy, one type of therapies enlists and strengthens the power of a patient’s immune system to attack tumors, has emerged as the “fifth pillar” of cancer treatment in the cancer community now.

A rapidly emerging immunotherapy approach is called adoptive cell transfer (ACT), collecting and using patients’ own immune cells to treat their cancer. There are three types of ACT, including tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), T cell receptor (TCR), and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

But, among them, CAR T-cell therapy is the only one which has advanced the furthest in clinical development. In this article, we introduce CAR-T cell therapy from six parts, including definition, process, development history, targets, challenges and others.

1. What is CAR-T Cell Therapy?

CAR-T refers to Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell, which is characterized by genetic modification to obtain a personalized therapeutic method for carrying T cells that recognize tumor antigen-specific receptors. CAR-T is able to sense cells with specific proteins on its surface through its own receptors, lock infected cells and cancer cells in this way, and then kill them. CAR-T cell therapy has been validated in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Personalized treatment produces significant results.

2. How it Works?

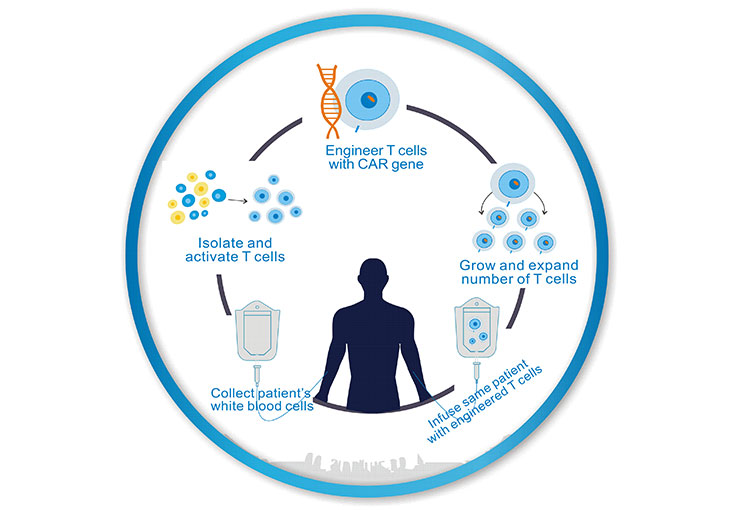

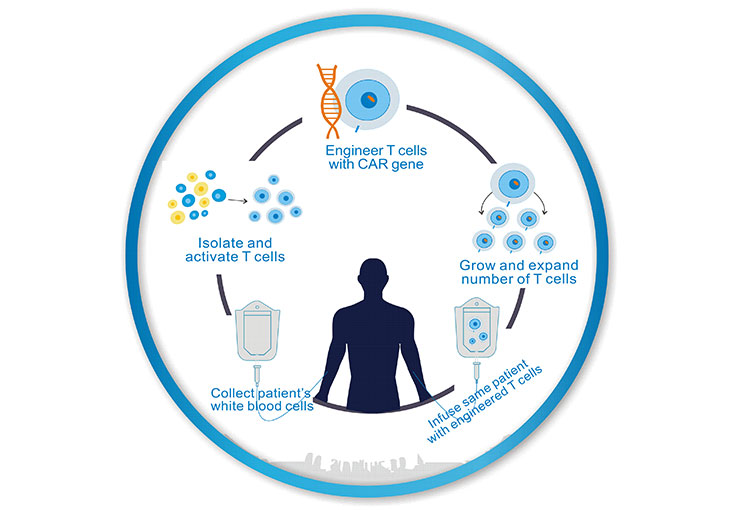

The process for CAR-T cell therapy can take a few weeks.

As the figure 1 shows, first, immune T cells are extracted from the patient’s blood using a procedure called leukapheresis by doctors.

Second, after the T-cells (a type of white cells) are removed from the patient, they are sent to the lab, and genetically altered by adding an artificial receptor (called a “chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)”) to their surface. This makes them CAR T-cells. The receptor functions as a type of “heat-seeking missile,” enabling the modified cells to produce chemicals that kill cancer.

Third, a large number of CAR-T cells are cultured in vitro, and generally one patient needs several billions or even ten billion CAR-T cells;

Once there are enough CAR-T cells, they will be given back to the patient to launch a precise attack against the cancer cells.

Figure 1. The Processes of CAR-T Cell Therapy

3. The History of CAR-T Cell Therapy Development

Actually, CAR-T technology has been used for many years, but it has been improved into clinical use in recent years as a new type of cell therapy. It has a remarkable effect on the treatment of acute leukemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and is considered to be the most promising tumor treatment.

Like all technologies, CAR-T technology has undergone a long process of evolution. It is in this series of evolution that CAR-T technology is gradually maturing. Here, we list three generations of CAR-T cell therapy as follows:

3.1. The First Generation of CAR-T Cell Therapy

The first generation of CAR-mediated T cell activation is accomplished by a tyrosine activation motif on the CD3z chain or FceRIg. The CD3z chain provides the signals required for T cell activation, lysis of target cells, regulation of IL-2 secretion, and in vivo anti-tumor activity. However, the anti-tumor activity of the first generation of CAR-modified T cells was limited in vivo, and the decrease in T cell proliferation ultimately led to the apoptosis of T cells.

3.2. The Second Generation of CAR-T Cell Therapy

The second generation of CAR added a new co-stimulatory signal in the cell, which made the original "signal 1" derived from the TCR/CD3 complex expand. Many studies have shown that the second generation equipped with "signal 2".

Compared with the first-generation CAR, the second generation CAR has no difference on antigen specificity. But its ability of T cell proliferation, cytokine secretion and secretion of anti-apoptotic proteins is better than the first-generation CAR. These features are the reasons for delayed cell death.

A commonly used costimulatory molecule is CD28, but studies have subsequently replaced CD28 with CD137 (4-1BB). In addition, an idea of ??using the NK cell receptor CD244 has also been proposed.

3.3. The Third Generation of CAR-T Cell Therapy

To further improve the design of CAR, many research groups began to focus on the development of third-generation CAR, including not only "Signal 1", "Signal 2", but also additional co-stimulatory signals.

There are some differences between the second generation CAR and To further improve the design of CAR, many research groups began to focus on the development of third-generation CAR, including not only "Signal 1", "Signal 2", but also additional co-stimulatory signals.

the third generation CAR obtained by different researchers using different targets and costimulatory signals. Some studies have reported that recombinant T cells expressing third-generation CAR have significantly improved antitumor activity, survival cycle, and cytokine release.

Wilkie et al. showed that second-generation CAR and third-generation CAR recombinant T cells targeting MUC1. There was no significant difference in anti-tumor cytotoxicity, although T cells expressing the third generation of CAR were able to secrete a greater amount of IFN-γ [1].

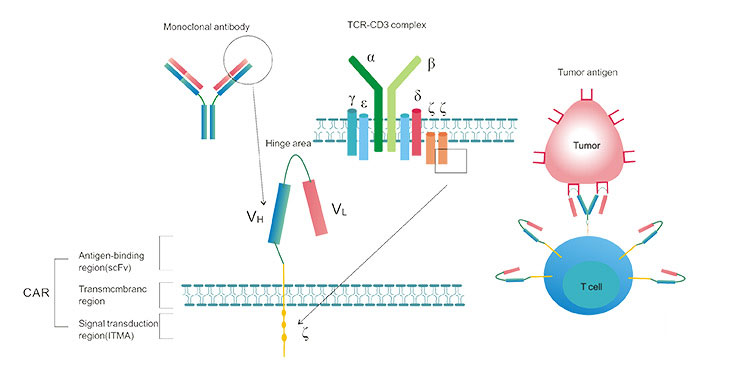

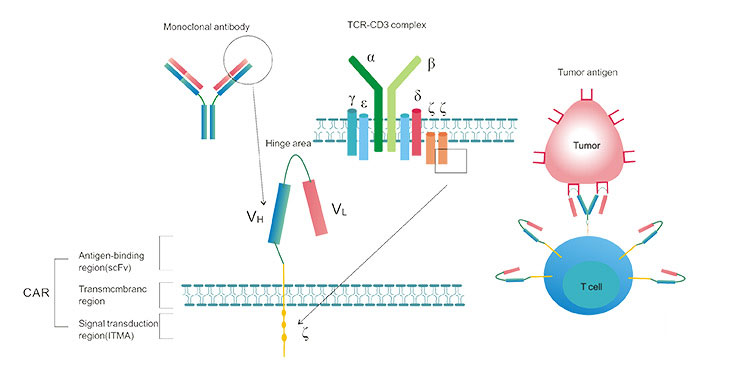

4. The Typical Structure of CAR-T

A typical CAR consists of an extracellular antigen binding region, a transmembrane region, and an intracellular signal transduction region. As shown in the figure 2, the antigen-binding region consists of a light chain (vl) and a heavy chain (vh) derived from a monoclonal antibody, and is joined by a tough hinge region to form a single chain fragment variable (scfv). The first key part of the CAR structure is a single-chain antibody that recognizes tumor antigens, which recognizes tumor-specific antigens, such as targets, such as CD19, EGFR, etc., rather than processing antigenic peptides that need to be processed.

Figure 2. The Typical Structure of CAR-T

5. The Targets of CAR-T Cell Therapy

In the past several years, clinical trials from several institutions to evaluate CAR-modified T cell (CAR-T cell) therapy for B cell malignancies such as B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (BNHL), have demonstrated promising outcomes by targeting CD19 [2] [3], CD20 [4], or CD30 [5]. Besides these, the target sites of CAR-T cell therapy also include CD22, CD123, CD133, PD-L1 and HER2 in current clinic.

-

CD19, also known as CD19 molecule (Cluster of Differentiation 19), is expressed in all B lineage cells, except for plasma cells, and in follicular dendritic cells in human. Mostly compelling success has been achieved in CD19-specific CAR-T cells for B-ALL with similar high complete remission (CR) rates of 70~94% [6].

-

CD20 is expressed on the surface of all B-cells beginning at the pro-B phase (CD45R+, CD117+) and progressively increasing in concentration until maturity. Several studies have suggested that CD20 is an ideal target antigen for NHL immunotherapy because it is almost universally expressed with high copy numbers on the surface of B-cell lymphomas and is minimally modulated [7] [8].

-

CD30, also known as TNFRSF8, is a cell membrane protein of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family and tumor marker. This receptor is expressed in many lymphoma subtypes, such as Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and represents very attractive target for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-based immune cell therapy.

-

CD22 is a molecule belonging to the SIGLEC family of lectins and a regulatory molecule that prevents the over-activation of the immune system and the development of autoimmune diseases [9].

-

CD123, also known as IL-3 receptor, is a molecule found on cells which helps transmit the signal of interleukin-3, a soluble cytokine important in the immune system. CD123 is expressed across acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtypes, including leukemic stem cells.

-

CD133, also known as prominin-1, is a member of pentaspan transmembrane glycoproteins, which specifically localize to cellular protrusions. CD133 is an attractive therapeutic target for CAR-T cell therapy as marker for isolation of cancer stem cell (CSC) population from different tumors, mainly from various gliomas and carcinomas.

-

PD-L1, also known as cluster of differentiation 274 (CD274), is a protein that is notably expressed on macrophages. And PD-L1 is a regulatory molecule expressed in T cells which has immune-regulatory function by dampening the immune response when bound to one of its complementary ligands.

-

HER2, also known as CD340, is a member of the human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER/EGFR/ERBB) family. Amplification or over-expression of this oncogene has been shown to play an important role in the development and progression of certain aggressive types of breast cancer. In recent years the protein has become an important biomarker and target of therapy for approximately 30% of breast cancer patients [10].

6. Other T Cell Therapy

As mentioned before, ACT can be divided into three types, including tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), T cell receptor (TCR), and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). In this part, we focus on the other two types except CAR.

6.1. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) is a lymphocyte isolated from tumor tissue. It is induced by IL-2 in vitro and has specific tumor killing activity. The main source is solid tumor tissue and infiltrating lymph nodes obtained by surgical resection. Because TIL has stronger tumor specificity than LAK and CIK, it is currently the main immunotherapy for research and application in the world.

6.2. T cell receptor

T cell receptor (TCR) gene therapy uses molecular biology to clone TCRs of tumor-specific T cells, and by constructing TCR-containing viral vectors, TCRs are transferred into normal T cells, making these T cells become tumor-specific TCRs. Specific tumor killer cells. In clinical trials that have been performed, TCR gene-transfected T cells can mediate regression of tumors, and these reinfused T cells can survive in vivo for more than half a year. The clinical efficacy of TCR gene therapy is relatively low. Finding effective tumor target antigen clones with high affinity TCR receptors and optimizing the transformation efficiency of TCR is the current research focus.

References

[1] Wilkie S, Picco G, et al Retargeting of human T cells to tumor associated MUC1: The evolution of a chimeric antigen receptor [J]. J Immunol. 2008, 180: 4901–4909.

[2] Maude SL, Frey N, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia [J]. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371(16):1507–17

[3] Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor [J]. J Clin Oncol. 2015, 33(6):540–9.

[4] Zhang W-y, Wang Y, et al. Treatment of CD20-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: an early phase IIa trial report [J]. Signal Transduction TargetTher. 2016, 1:16002.

[5] Wang CM, Wu ZQ, et al. Autologous T Cells expressing CD30 chimeric antigen receptors for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: an openlabel phase I trial [J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2016.

[6] Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor [J]. J Clin Oncol. 2015, 33(6):540–9.

[7] Bindon CI, Hale G, et al. Importance of antigen specificity for complement-mediated lysis by monoclonal antibodies [J]. Eur J Immunol 1988; 18: 1507–1514.

[8] Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias [J]. Blood. 2011; 118: 4817–4828.

[9] Hatta, et al. Identification of the gene variations in human CD22 [J]. Immunogenetics. 1999, 49 (4): 280–286.

[10] Mitri Z, Constantine T, et al. The HER2 Receptor in Breast Cancer: Pathophysiology, Clinical Use, and New Advances in Therapy [J]. Chemotherapy Research and Practice. 2012, 743193.

CUSABIO team. CAR-T Cell Therapy- An Useful Treatment To Cancer. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20922.html

Comments

Leave a Comment