At the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting, the team of Michael J. Birrer, MD, et al. proposed that CD31 is a potential biomarker for bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. Because the effect of bevacizumab on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) appeared most pronounced in patients with high CD31. This discovery brings more attention to CD31, although there were several researches of CD31 before. In this article, we briefly introduce the fundamental knowledge of CD31 from the following sections:

1. What is The CD31?

Cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31), also known as platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1), is a protein encoded by the PECAM1 gene found on chromosome 17 in humans. This molecule was first identified in the mid-1980s as the CD31 differentiation antigen expressed on the surface of human granulocytes, monocytes, and platelets [1] [2]. In 1990, Newman et al. reported the molecular cloning of a 130kDa cell-surface protein designated platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1). Since then, there has been considerable progress in understanding the structural and functional aspects of this molecule. Out of these efforts has emerged the concept of PECAM-1 as a vascular cell adhesion molecule involved in diverse processes and capable of multiple ligand interactions [3].

2. What is The Structure of CD31?

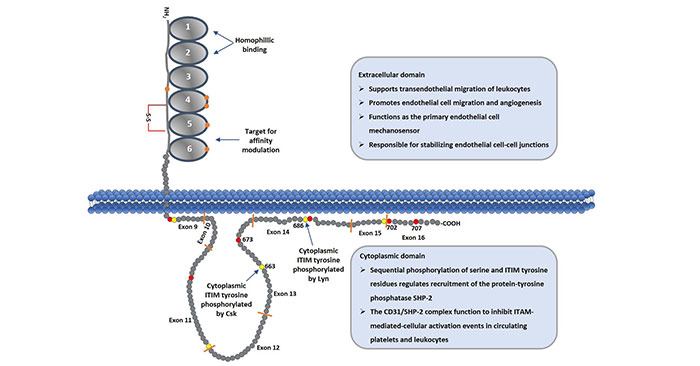

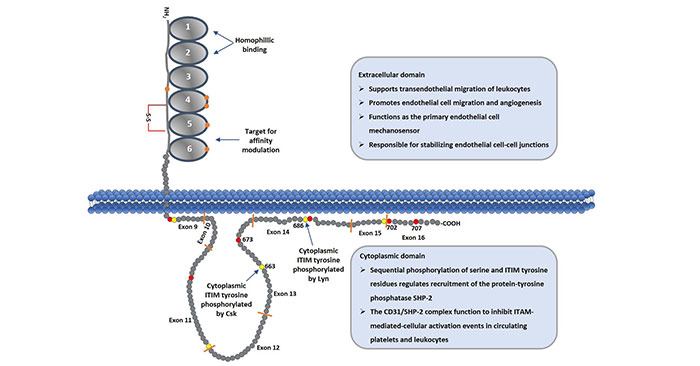

PECAM1/CD31 is a transmembrane glycoprotein with a molecular mass of 130kDa which probably varies slightly between different cell types, presumably due to glycosylation differences. Human CD31 is composed of a large extracellular domain of 574 amino acids, a single membrane-spanning region of 19 hydrophnbic residues and a cytoplasmic domain of 118 amino acids. Here, we focus on the extracellular and cytoplasmic domains. As the figure 1 shows:

Figure 1. Schematic Diagram of CD31 Protein

2.1 Extracellular Domain

The 574 amino acid extracellular region is organized into six immunoglobulin homology domains of the C2 subclass, which are similar to those found in the lg superfamily members that function as cell adhesion molecules. And each of immunoglobulin homology domains is approximately 100 amino acids. The first two of IgD (IgD1 and IgD2) are shown as a space-filling model of the homophilic binding domain that is involved in cell adhesion and as regulator of vascular permeability [4].

2.2 Cytoplasmic Domain

The structure of the cytoplasmic domain was determined by two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance, and is characterized by two lipid-associated regions separated by a large unstructured region. Generally, the PECAM-1 gene is organized into 16 exons (numbered open boxes) that are separated by introns of widely variable length. In the cytoplasmic domain, it is comprised of eight separate exons (as the figure 1 shows from exon9-exon16). These exons are subject to alternative splicing, yielding isoforms that are expressed in a tissue, and differentiation-specific manner, and that have the potential to differ in their functional properties [5]. In this domain, the presence of several serine, threonine and tyrosine residues may represent sites of phosphorylation following cell activation [6].

3. What is The Co-receptor for CD31?

Accumulating evidences have demonstrated that CD31 itself is an important molecule as a co- or counter-receptor for CD31. Homophilic interactions are well established, and appear to be mediated by the first and second C2 domains of the CD31 molecule. Additionally, IgSF/CAMs is also reported of integrin binding to CD31. In particular, the alphavbeta3 (or CD51/CD61) integrin has been suggested to be a CD31 co-receptor. Although the integrin is expressed on T cells, NK cells, mast cells and endothelium, it is somewhat unusual as an IgSF ligand because all other ICAM/VCAM receptors are either beta1, beta2 or beta7 integrin types.

4. What is The Function of CD31?

As mentioned, CD31 expression is restricted to blood and vascular cells. In circulating platelets and leukocytes, CD31 functions mainly as an inhibitory receptor that, via regulated sequential phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic domain, limits cellular activation responses. PECAM-1 is also highly expressed at endothelial cell intercellular junctions, where it functions as a mechanosensor, as a regulator of leukocyte trafficking, and in the maintenance of endothelial cell junctional integrity.

Most activities associated with CD31 can be attributed to homophilic CD31-CD31 interactions. Among these are leukocyte extravasation, bone marrow hematopoiesis, and vascular development. During the events surrounding leukocyte extravasation, CD31 seems to be most important during the later stages.

In particular, CD31 appears to facilitate the binding of various leukocyte-associated integrin to ICAM/VCAM IgSF members and assist peripheral blood leukocytes in their transit across endothelial barriers. Facilitation of CAM-IgSF binding appears to be due to a general upregulation of beta1 and beta2 integrin activity following leukocyte CD31-endothelial cell CD31 engagement.

5. The Signaling Pathway of CD31

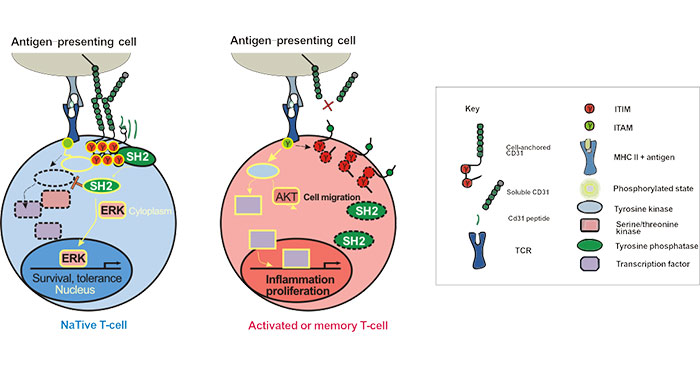

As mentioned in the part of 2.2, there are many serine, threonine and tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain. And PECAM-1-mediated signaling is generally initiated by phosphorylation of serine 702, which releases ITIM tyrosine 686 from its association with the plasma membrane, facilitating its phosphorylation by the Src-family kinase, Lyn. Sequential phosphorylation of ITIM tyrosine 663 completes the process, and allows PECAM-1 to now recruit Src homology 2 domain-containing proteins, the most notable of which is the protein-tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2.

Recently, one study from Federica M. Marelli-Berg’s team has revealed the mechanism of CD31 function in T cells. In na?ve T-cells, downregulation of surface expression of CD31 has been associated with homeostatic proliferation, which is responsible for the maintenance of the pool of T-cells when thymic output is reduced. In memory T cells, CD31 regulates the trafficking of memory T-cells, but it does not appear to affect their activation [7].

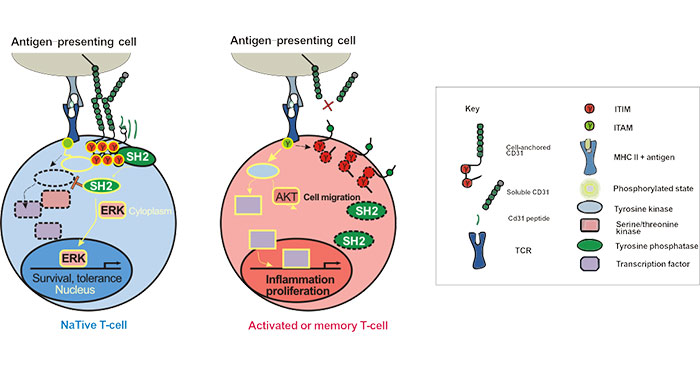

The most distinctive feature of CD31 is the presence of two ITIMs in its cytoplasmic domain. These ITIMs are phosphorylated following TCR activity and subsequently recruit protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), such as the Src homology 2 (SH2)-domain-containing protein SHP-2, leading to inhibition of TCR signaling. As the figure 2 shows [8]:

Figure 2. CD31 Signaling Pathways in T-lymphocytes

6. CD31 and Diseases

CD31 is expressed by all leukocytes, including T-, B-lymphocytes and dendritic cells. The complexity of the biological functions of CD31 results from the integration of its adhesive and signaling functions in both the immune and vascular systems. The abnormal expression of CD31 has relationship with several diseases, such as atherosclerosis, inflammation and hematologic disease.

6.1 CD31 and Atherosclerosis

In the progression of atherosclerosis, CD31 mainly plays role in the stability of coronary plaque. First, in patients with myocardial infarction (MI), the platelet CD31 complex concentration is elevated, and the concentration of anti-CD31 antibody in the infarct zone is decreased [9]. Second, platelet CD31 complex expression is elevated in delayed or failed thrombolysis patients. In addition, studies have confirmed that peroxidase has an anti-angiogenic effect, while CD31 affects the contact of the enzyme with the endothelium, thereby mechanically controlling the atherosclerosis process.

Therefore, it is speculated that CD31 gene mutation has a profound impact on the progression of coronary heart disease. Furthermore, studies have found that angina pectoris, acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, sudden death, etc. are all occurring between 6 am and 12 am. This is consistent with the level of PECAM-1 at night and peak in the morning. In the mouse experiment, PECAM-1 plays an important role in platelet aggregation [10].

6.2 CD31 and Inflammation

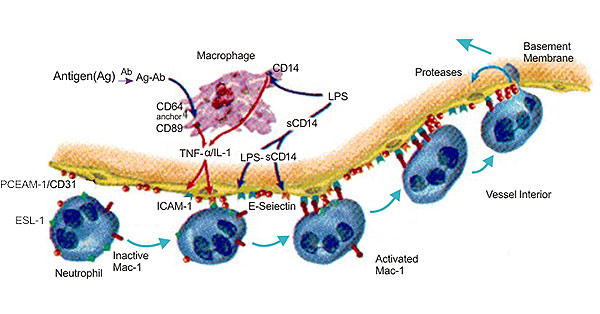

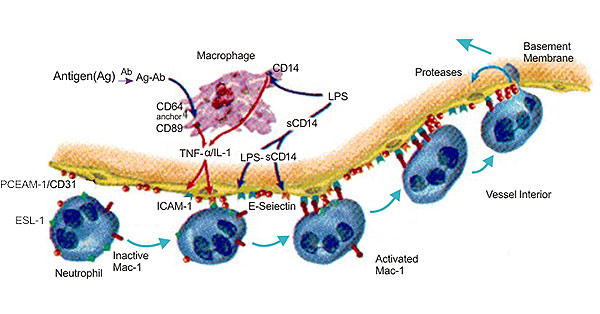

Many studies have indicated that CD31 is involved in inflammation. During the inflammatory process, CD31 plays role in the beginning of inflammation. CD31 is the main component of leukocyte extravasation, and its expression promotes leukocyte migration. The specific anti-CD31 antibody and the soluble CD31 protein that inhibits endothelial cell adhesion can inhibit the migration of leukocytes; it can also block the migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells [11], and it can also block the migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

Figure 3. The Diagram of CD31 and Inflammation

During the migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes across endothelial cells, the adhesion of CD31 is lysed, and after the cells complete the migration, the adhesion is restored, which may be related to the Ca2+ channel. In addition, homologous binding of CD31 also plays an important role in leukocyte migration. It has been reported that CD31, CD99 and JAM are involved in the migration of leukocytes across endothelial cells. JAM adheres to leukocytes by endothelial cells through the action of its ligand LFA-1. CD31 mediates leukocyte extravasation, and CD99 determines leukocyte transendothelial cells. The completion of the process, this discovery provides new ideas for the study of the mechanism of inflammatory response [12] [13].

6.3 CD31 and Hematologic Disease

Karen Ballen et al. discovered that the levels of CD31 and CD44 in bone marrow and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of the aplastic anemia group were significantly lower than those of the normal control group in peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with aplastic anemia [14].

Correlation analysis showed that the levels of CD31 and CD44 in bone marrow and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were positively correlated with the number of peripheral blood leukocytes, hemoglobin, platelets, granulocyte ratio in bone marrow, erythroid ratio, and megakaryocytes. It is suggested that abnormal expression of adhesion molecules may play a role in the pathogenesis of aplastic anemia.

Gordon et al.'s research suggests that cell adhesion molecules can target targeting sites, allowing naive hematopoietic cells to adhere to the bone marrow stroma and provide regulatory signals that allow for further differentiation of naive hematopoietic cells before they are released from the bone marrow. It is believed that the reduction of the three lines of aplastic anemia is closely related to the defect of adhesion molecule expression, and it is one of the important factors for aplastic anemia. However, its exact mechanism of action still needs further discussion [15].

References

[1] 10hto, H., Maeda, H., et al. Blood. 1985, 66,873-88.

[2] AIbelda, S.M., Oliver, P.D., et al. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 110, 1227-1237.

[3] Horace M. DeLisser, Peter J. Newman, et al. Molecular and functional aspects of PECAM-I/CD31 [J]. Immunology Today. 1994, 15(10):490-495.

[4] Paddock C, Zhou D, et al. Structural basis for PECAM-1 homophilic binding [J]. Blood. 2016, 127:1052–1061.

[5] Paddock C, Lytle BL, et al. Residues within a lipid-associated segment of the PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain are susceptible to inducible, sequential phosphorylation [J]. Blood. 2011, 117:6012–6023.

[6] Panida Lertkiatmongkol, Danying Liao, et al. Endothelial functions of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31) [J]. Vascular biology. 2016, 23(3):253-259.

[7] Manes, T. D., Hoer, S., et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 and K5 proteins block distinct steps in transendothelial migration of effector memory CD4+ T cells by targeting different endothelial proteins [J]. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 5186–5192.

[8] Federica M. Marelli-Berg, Marc Clement, et al. An immunologist's guide to CD31 function in T-cells [J]. Journal of Cell Science. 2013, 126: 2343-2352.

[9] Nounhargh S.Krombach F, et al. The role of JAM-A and PECAM?l in modulating leukocyte infiltration in inflamed and ischemic tissues [J]. J Lonkoc Biol. 2006, 80(4):714—718.

[10] Kalinowska A,Losy J.PECAM-1,a key player in neuro-inflammation[J]. Eur J Neurol. 2006, 13(12):1284-1290.

[11] Dangerfiled J, Larbi KY, et al. PECAM-1(CD31) hemophilic interaction up-regulated α6β1 on transmigrated neutrophils in vivo and play a functional role in the ability of α6 integrins to mediate leukocyte migration through the perivascular basement membrane [J]. J Exp Med. 2002, 196(9): 1201-1211.

[12] Ostermann G, Weber KSC, et al. JAM-1 is a ligand of the β2 intergrin LFA-1 involved in transendothelial migration of leukocytes [J]. Nature Immunol. 2002, 3(2):151-158.

[13] Schenkel AR, Mamdouh Z, et al. CD99 plays a major role in the migration of monocytes through endothelial junctions [J]. Nature Immunol. 2002, 3(2):143-150.

[14] Karon Ballen, Pamela S, et al.Effect of ex vivo cytokine treatment on human cord blood engraftment in NODseid mice[J].Br J Haematol. 2001, 108(3):629-640.

[15] Gordon MY, Clark D, et al. Hemopoietic progenitor cell binging to the stromal microenvironment in vitro [J]. Exp Hematol. 1990, 18(7):837.

CUSABIO team. CD31- A Complex Function Molecule. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20954.html

Comments

Leave a Comment