CD46 was discovered in 1986 by Cole et al. using C3b affinity chromatography on peripheral blood lymphocytes [1]. CD46, also known as membrane co-protein (MCP), is a membrane protein. The nucleotide sequence of MCP is homology to the decay accelerating factor (DAF) but their protein structures and functions are different. Based on this feature, CD46 is considered as a new regulatory protein of the complement system and named CD46 at the 4th International Leukocyte Typing Meeting. With the deepening of the understanding of CD46, people gradually realized that it is a membrane protein with multiple functions and is associated with various immune diseases. What exactly is the CD46? What role does it play in the immune system? More information about these questions, please view the following parts:

1. what is CD46?

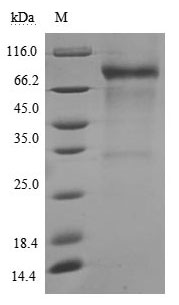

CD46 gene is located in the 32 region of human short arm of chromosome 1 and has a molecular weight of 45-70 kDa, also named gp45-70, belonging to the family of complement activation regulatory protein factors.

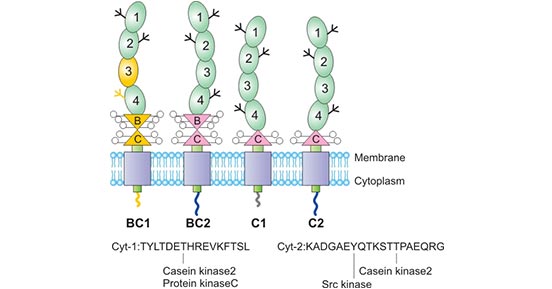

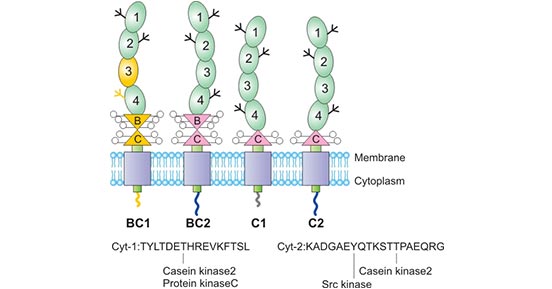

As the Figure 1 shows, CD46 is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that is expressed on most tissues as four major isoforms derived by alternative splicing of a single gene. The N-terminus of each isoform consists of four complement control protein repeats (CCPs), and CCPs 1, 2 and 4 each bear one N-linked complex sugar. The CCPs are followed by a serine, threonine and proline-rich (STP) region that is heavily O-glycosylated. The STP region, a site of alternative splicing, arises from three separate exons, designated A, B and C. The four major isoforms of CD46 utilize the C region, whereas the B region is alternatively spliced, giving rise to either a BC or C STP region.

Isoforms containing the A exon of the STP region have been reported, but are rarely observed in normal human tissue. CD46 is divided into four subtypes according to different combinations: C1, C2 and BC1, BC2. The BC subtype has a larger molecular weight than the C subtype [2] [3] [4]. The STP region is followed by a 12 amino acid region of unknown function, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic anchor. The carboxyl terminus of CD46 is also differentially spliced, giving rise to two distinct cytoplasmic tails, designated CYT-1 and CYT-2. CYT-1 is 16 amino acids long and contains a casein kinase II phosphorylation site and a protein kinase C phosphorylation site. CYT-2 is 23 amino acids long and contains a src kinase site as well as a casein kinase II site.

Figure 1. The structure of CD46

CD46 is widely distributed on most of the normal cell surface, including hematopoietic cell lines, fibroblasts, epidermal cells, endothelial cells and stellate cells, but the number of cells expressed on different types of cells is Different [5]. For example, the C2 subtype is mainly expressed in the brain and sperm, while the BC subtype is expressed more in the kidney, salivary gland, and infant heart.

2. What is the function of CD46?

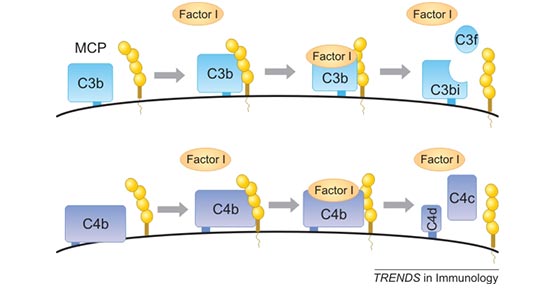

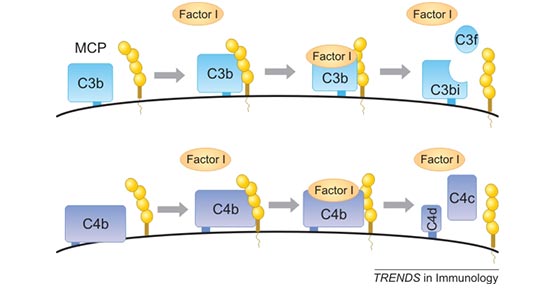

Human CD46, also known as membrane cofactor protein (MCP), belongs to the family of complement activation regulator (RCA) proteins. Except for CD46, the RCA family also includes decay accelerating factors (CD55 / DAF), complement receptor 1 (CR1 / CD35) and 2 (CR2 / CD21), C4 binding protein and factor H (FH). As shown in Figure 2, CD46 acts as a factor I-mediated C3b and C4b cleavage cofactor and is a key regulator of the classical and selective complement activation cascade in the innate immune system [6]. Cleavage of excess C3b produces membrane-bound C3bi and soluble C3f. Cleavage of C4b can result in membrane-bound C4d and soluble C4c. Cell-bound cleavage fragments cannot continue to activate the complement cascade. This process protects host cells from accidental lysis of the complement system [7] [8].

Figure 2. CD46 is a cofactor for the serine protease factor I to cleave C3b and C4b

In recent years, CD46 related reports have not been limited to the innate immune system. Numerous studies have shown that CD46 can regulate T cell immunity, especially to control inflammation [9] [10]. In addition to its role in the regulation of complement activation and adaptive immune response, CD46 is also used as a cellular receptor by a variety of viruses and bacteria.

Some measles viruses (MV) and adenovirus (Adv) attach to cells by binding to CD46. Although other members of the RCA protein family also bind to viruses, pathogens that bind to CD46 are still predominant. CD46 is also known as "the magnet of pathogens" [11]. As mentioned in the first part, CD46 is widely distributed on the cell surface, and all nucleated cells express CD46, which is also the main reason for its prominent position in pathogen interaction. Accumulating studies have shown that the interaction of CD46 with pathogens down-regulate CD46 levels in cells, thereby increasing the complement sensitivity of infected cells [12]. A recent study revealed a direct link between CD46 and autophagy-related factors. The recognition of pathogens by CD46 triggers autophagy, which is also a key step in controlling infection [13].

3. CD46 and Immune

3.1 CD46 and Innate Immune

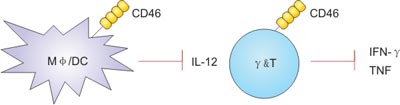

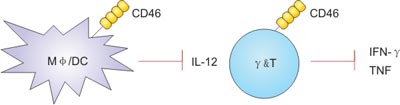

Innate immunity, also called non-specific immunity, refers to the fact that an individual has a wide range of effects at birth and is not immune to a specific antigen. It plays an important role in the body's defense mechanism and is the first line of defense against pathogenic microbial infections. CD46 interacts with natural and pathogenic ligands to inhibit the production of interleukin IL-12 in mouse and human macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). In addition, CD46-mediated signaling directly inhibits the production of the effector cytokine IFNγ in γδT cells.

In addition to the role of CD46 signaling on macrophages, dendritic cells and epithelial cells, the role of CD46 in other innate immune cells including NK cells, NK T cells, mast cells, neutrophils and monocytes Still to be further studied. Only one in vitro study has found that CD46 is reduced in cell killing activity after recruitment on NK cells [14].

Figure 3. CD46 modulates innate cell functions

3.2 CD46 and Adaptive Immune

Adaptive immunity, also known as acquired immunity or specific immunity, is directed against specific pathogen. It is the ability of the body to resist infection after infection or artificial vaccination. It is usually formed after stimulation of antigenic substances such as microorganisms (immunoglobulin, immune lymphocytes), and specifically reacts with the antigen.

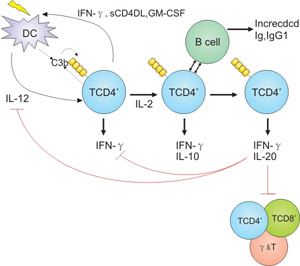

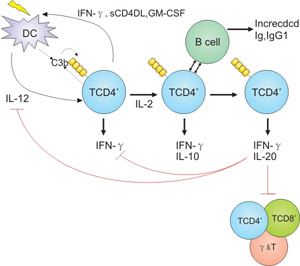

Initially, a study by Astier et al. discovered that CD46 acts as a costimulatory molecule on human CD4+ T cells and induces high cell proliferation after activation during antigen presentation. Once the study was published, a series of studies were carried out on this discovery and it was finally demonstrated that CD46 induced the activation or production of IL-10-regulatory T cells (Treg) during T cell activation.

Due to the therapeutic potential of Treg in autoimmune diseases and transplant rejection, research related to Treg is also increasing. Treg plays a key role in inhibiting and regulating the Th1, Th2 and Th17 T cells activation. As shown in Figure 4, the production of IL-2 and C3b was low during the induction phase of the Th1 response, proliferation and secretion of IFN-γ-type Th1 cells to control infection. Amplification of Th1 effector cells can fully enhance IL-2 secretion to induce IL-10 co-expression and regulation [15] [16] [17].

Figure 4. Regulation of adaptive T cell responses

4. CD46 and Disease

A large number of studies have demonstrated that CD46 is associated with a variety of immune-inflammatory diseases. Sandra et al. found that high expression of CD46 in people who have quit smoking prevent emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused by autoimmune and inflammatory reaction. In the process of multiple sclerosis, the lack of CD46 affects the proliferation and differentiation of T cells, leading to a decrease in the secretion of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 [18]. Jones et al. tested the expression of CD46 in the neutrophils of synovial fluid and peripheral blood in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This study found that the expression of CD46 in synovial fluid is higher. It indicated that the change of CD46 expression in synovial joints of rheumatoid arthritis enhances the ability of cell adhesion, complement resistance, and immune complexes clearance of Neutrophil [19].

Moreover, the expression of CD46 also changed significantly in tumor escape and ischemia-reperfusion. In summary, we suppose that CD46 inhibits the activation of the complement system to reduce the immune response and decrease the production of anti-inflammatory factors by regulating T cells, ultimately affecting the inflammatory response.

In addition, M. Kathryn Liszewski et al. found that CD46 mutations are closely related to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. The causes of aHUS precipitation include infection, pregnancy, trauma, or drugs. It is unclear why the renal endothelium is the main site of organ damage. However, it is clear that the cause of this disease is the inability to control the alternative pathway (AP) on the surface of damaged or stressed cells, leading to "self-healing" hyper-activation. The dysfunction of mutant protein may be due to loss of function or acquired function. Both of them lead to a decrease in C3b degradation efficiency and a sustained activity of C3 and C5 convertase, resulting in an excess of complement pathway effectors.

In addition, C5b initiates assembly of the MAC, resulting in membrane damage, while C5a recruits and activates leukocytes and upregulates vascular adhesion. Since the function of endothelial cells is interfered with the delicate balance between complement activation and complement regulation, thrombotic microangiopathy follows, thickening of the vessel wall, cell congestion and destruction [20].

5. CD46 Clinical Drug Information

| Name |

Research Code |

Research Phase |

Company |

Indications |

| Enadenotucirev |

ColoAd-1; Oncolytic Ad11/Ad3 |

Phase Ⅱ |

PsiOxus Therapeutics, Merck Sharp & Dohme |

Urogenital cancer, Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Colorectal cancer, Bladder cancer, Ovarian cancer, Renal carcinoma |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing measles virus (National Cancer Institute) |

/ |

Phase Ⅰ |

National Cancer Institute |

Glioma, Glioblastoma, Primary Peritoneal Cavity Cancer, Ovarian cancer, Anaplastic astrocytoma |

| AugmAb |

BRM-132 |

Phase Ⅰ |

BRIM Biotechnology, PAI Life Sciences |

Cancer |

| FOR-46 |

FOR-46,FOR 46,FOR46 |

Phase Ⅰ |

University of California San Diego |

Prostate cancer, Multiple myeloma (MM) |

References

[1] Cole JL, Housley GA Jr, et al. Identification of an additional class of C3-binding memberane protein of human peripheral blood leukocyters and cell lines [J]. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985, 85:859-863.

[2] J. Cardone, G. Le Friec, et al. CD46 in innate and adaptive immunity: an update [J]. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2011, 164: 301–311.

[3] Le Friec G, Kemper C. Complement: coming full circle [J]. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2009, 57:393–407.

[4] Gill DB, Atkinson JP. CD46 in Neisseria pathogenesis [J]. Trends Mol Med. 2004, 10(9):459-65.

[5] B. David Persson, Nikolaus B. Schmitz, et al. Structure of the Extracellular Portion of CD46 Provides Insights into Its Interactions with Complement Proteins and Pathogens [J]. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6(9): e1001122.

[6] Seya T, Turner J, et al. Purification and characterization of a membrane protein (gp45–70) that is a cofactor for cleavage of C3b and C4b [J]. J Exp Med. 1986, 163:837–855.

[7] Liszewski MK, Post TW, Atkinson JP. Membrane cofactor protein (MCP or CD46): newest member of the regulators of complement activation gene cluster. Annu Rev Immunol [J]. 1991. 9:431–455.

[8] Rebecca C. Riley-Vargas, Darcy B. Gill, et al. CD46: expanding beyond complement regulation [J]. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25(9):496-503.45.

[9] Astier AL. T-cell regulation by CD46 and its relevance in multiple sclerosis. Immunology [J]. 2008, 124:149–154.

[10] Griffiths MR, Gasque P, et al. The multiple roles of the innate immune system in the regulation of apoptosis and inflammation in the brain [J]. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009, 68:217–226.

[11] Cattaneo R. Four viruses, two bacteria, and one receptor: membrane cofactor protein (CD46) as pathogens' magnet [J]. J Virol. 2004, 78:4385–4388.

[12] Sakurai F, Akitomo K, et al. Downregulation of human CD46 by adenovirus serotype 35 vectors [J]. Gene Ther. 2007, 14:912–919.

[13] Joubert PE, Meiffren G, et al. Autophagy induction by the pathogen receptor CD46 [J]. Cell Host Microbe. 2009, 6:354–366.

[14] Al-Shouli S, Cardone J, et al. Let’s connect: a novel role for CD46 in tight junction regulation [J]. Mol Immunol. 2010; 47:2252–3.

[15] Cardone J, Le Friec G, et al. Complement regulator CD46 temporally regulates cytokine production by conventional and unconventional T cells [J]. Nat Immunol. 2010; 11:862–71.

[16] Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, et al. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system [J]. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010; 10:490–500.

[17] Barrat FJ, Cua DJ, et al. In vitro generation of interleukin 10-producing regulatory CD4(+) T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-inducing cytokines [J]. J Exp Med. 2002; 195:603–16.

[18] AstierAL. T-cell regulation by CD46 and its relevance in multiple sclerosis [J]. Immunology. 2008, 124(2):149-154.

[19] Alvarez afuente R, Blanco Kelly F, et al. CD46 in a Spanish cohort of multiple sclerosis patients: genetics, mRNA expression and response to interferon beta treatment [J]. Mult Scler. 2011, 17(5):513-520.

[20] M. Kathryn Liszewski and John P. Atkinson. Complement regulator CD46: genetic variants and disease associations [J]. Hum Genomics. 2015; 9(1): 7.

CUSABIO team. CD46, A Complement Regulator. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20977.html

Comments

Leave a Comment