As is well-known, post-translational modifications (PTMs) are essential mechanisms for eukaryotic cells to diversify protein functions and dynamically coordinate

signaling networks. Vincent Allfrey and colleagues first discovered lysine acetylation modifications on histones in 1964. Subsequently, mass spectrometer-based proteomics has greatly accelerated the

discovery and identification of endogenous acetylated proteins and also revealed the regulatory process of non-histone acetylation. Acetylation modification is an evolutionarily conserved PTM that exists in

both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In the following sections, we will focus on the definition, function, mechanisms, and diseases associated with protein acetylation.

1. What Is Protein Acetylation?

Protein acetylation is one of the major post-translational modifications (PTMs) in eukaryotes, in which the acetyl group from

acetyl coenzyme A (Ac-CoA) is introduced to a specific site on a polypeptide chain [1]. Proteins are acetylated either on various amino-terminal residues or the ε-amino group of lysine residues.

The majority of eukaryotic proteins and regulatory peptides undergo acetylation at amino-terminal residues, whereas lysine acetylation occurs at different sites of diverse proteins, including histones and

transcription factors.

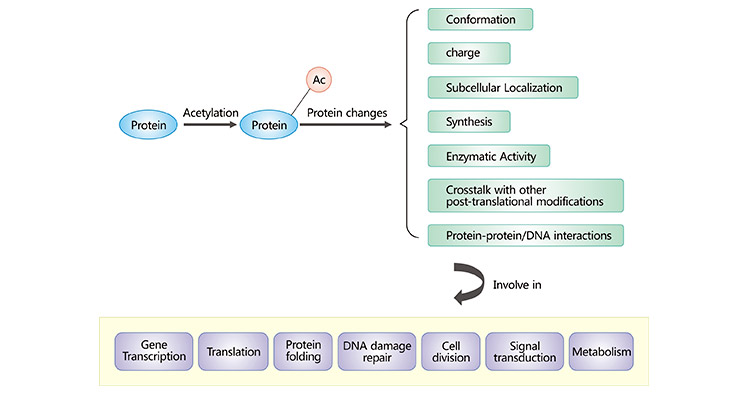

2. The Functions of Protein Acetylation

The majority of human proteins undergo acetylation. Acetylation of proteins can affect protein charge, conformation, stability,

localization, synthesis, and interactions with other molecules. Numerous acetylated proteins have been identified to participate in diverse cellular processes, such as translation, transcription, protein

folding, cell division, DNA damage repair, signal transduction, and metabolism. Acetylation of histones can reduce their positive charge, weaken their ability to bind to DNA, and cause nucleosome

depolymerization, enabling transcription factors and RNA polymerase to bind to DNA smoothly and activating the transcriptional activity of genes. It was discovered that acetylation could affect the enzyme

activity of nucleases, thereby regulating the level of substrate RNA [7]. Acetylation also regulates more than 100 non-histone proteins, including transcription factors, transcriptional

coactivators, and nuclear receptors [8]. Non-histone protein acetylation complicates cellular function whereas acetylation of key mitochondrial enzymes regulates bioenergetic metabolism.

Protein acetylation is also associated with protein degradation. Besides, protein acetylation can regulate a variety of signaling pathways and affect the cell cycle.

Figure: The roles of protein acetylation in eukaryotic cells

3. Mechanisms for Protein Acetylation

The most widely studied protein acetylations occur on amino groups, although acetylations on serine, threonine, and

histidine residues of proteins also have been detected. Three distinct mechanisms for acetylation of amino groups of proteins can occur lysine acetylation (Nɛ-acetylation), N-terminal protein acetylation (N

α-acetylation), and O-acetylation.

3.1 Nɛ-Lysine Acetylation

Lysine acetylation, also known as the Nɛ-lysine acetylation, describes the transfer of an acetyl group from acetyl-coenzyme A

(acetyl-CoA) to the primary amine in the ɛ-position of the lysine side chain within a protein. This reversible process neutralizes the positive charge of the ɛ-position of the lysine side chain. Loss of the

positive charge and increase of the size of lysine disrupts salt bridges and introduces steric bulk, changing protein-protein/DNA interactions, stability, and enzymatic activity [2] [3].

Potent evidence shows that protein lysine acetylation can occur via two distinct mechanisms: enzymatic and nonenzymatic acetylation (chemical

acetylation) [4]. Two distinct mechanisms show a preference for different lysine acetylation sites and reveal different dynamics of relative acetylation changes at these lysine sites.

Enzymatic acetylation relies on an Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase to catalyze the transfer of the acetyl group from acetyl-coenzyme A (Ac-CoA) to the ɛ-

amino group of a lysine residue. Nonenzymatic acetylation occurs between an acetyl donor and a protein. In eukaryotic cells and specifically within mitochondria, the high-energy thioester AcCoA can

chemically acetylate proteins [16].

3.2 Nα-acetylatio

Nα-acetylation refers to the addition of an acetyl group to the α-amino group of the N-terminal amino acid. It is a typically

irreversible process and is mediated by N-alpha-acetyltransferases (NATs). Approximately 85% of human protein is modified by Nα-acetylation [5]. Nα-acetylation is very common and co-

translational in eukaryotes but is rare and post-translational in bacteria [17]. In eukaryotic cells, Nα-acetylation is observed either on the free amino group of methionine or the exposed amino

acid after cleavage of the N-terminal methionine. Nα-acetylation is post-translational in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts because the methionine first must be deformylated.

3.3 O-acetylatio

O-acetylation refers to the addition of an acetyl group to the hydroxyl group of the tyrosine/serine/threonine residue [6]. It has been identified as the third type of protein acetylation. The Yersinia outer protein J (YopJ) acetylates the side-chains of serine and threonine residues required for activation of the

MAPK/ERK kinase and IκB kinase families, thus blocking their phosphorylation and inhibits signal transduction. O-acetylation of sialic acid in protein N-glycans is an important modification and can occur at

either 4-, 7-, 8- or 9-position in various combinations.

4. Protein Acetylation and Diseases

Acetylation and deacetylation of functional proteins play important roles in embryonic development, postnatal maturation,

cardiomyocyte differentiation, cardiac remodeling, and the onset of various cardiovascular diseases (including obesity, diabetes, cardiometabolic diseases, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and heart

remodeling, Hypertension, and arrhythmia) [10] [11].

Jie Ouyang et al. demonstrated that the elevation of SOD2 and p53 protein acetylation in the mitochondria of renal tubular epithelial cells is an

important signaling event in the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) [9]. Some studies also suggest that restoring the activity of SIRT1/3 may be a novel

therapeutic target for AKI. SIRT1 and 3 are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent protein deacetylases and play a role in anti-oxidative stress and anti-apoptotic effects to protect kidney function.

Using resveratrol, the activity of SIRT1/3 can be restored efficiently. Studies showed that K136 acetylation of TDP-43 impairs its RNA binding and splicing capabilities, promoting the accumulation of

insoluble aggregates with pathologically phosphorylated and ubiquitinated TDP-43, which is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The acetylation of some proteins is associated with carcinogenesis. Compared to corresponding non-tumor tissue cells, colon cancer-associated

transcription factor 1 (CCAT1) is remarkably higher in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) cells [12]. It is well-known that high expression of CCAT1 promotes cell proliferation and

invasion, while downregulation of CCAT1 can inhibit the two biological processes [13]. The acetylation of H3K27 has been reported to partially upregulate the expression of CCAT1, which has

the potential to induce cancer [14]. Moreover, glycolysis provides cancer cells a large amount of energy to rapidly proliferate. Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), an important reductase in the

glycolysis process, if acetylated, may change the proliferation of cancer cells. In liver cancer cells, the activity of PGK1 enhances due to acetylation and further accelerates the proliferation of tumor cells [15].

Advancing mass spectrometry combined with biology has enabled the localization of a large number of acetylation sites in all proteins. Mounting

studies have shown that acetylation is one of the most abundant chemical modifications in nature and may affect various physiological processes of proteins and even lead to some diseases. Therefore,

protein acetylation is also a promising target for the development and design of new drugs for many diseases in recent years.

5. Acetylation-related Products

Many acetyltransferases involve in the acetylation of proteins. Here, CUSABIO provides some premium acetyltransferases to

scientific researchers for their protein acetylation-associated research.

|

Acetylated Proteins

|

Acetyltransferases

|

|

Human proteins

|

NatA (catalytic subunit: Naa10, Naa15 ), NatB (Naa20, Naa25), NatC (Naa30, Naa35, Naa38), NatD (Naa40), NatE (Naa50), NatF (Naa60), NatH (Naa80)

|

|

Histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4)

|

Gcn5, PCAF, Hat1, Elp3, Hpa2, Esa1, MOF, Sas2, Sas3, Tip60, MORF, TAFII250, TFIIIC, ACTR, and SRC1.

|

|

E. coli ribosomal proteins (S18, S5, and L12)

|

RimI, RimJ, RimL

|

|

Transcription factors (p53, E2F1-3, EKLF)

|

PCAF/Gcn5, p300/CBP, TAFII250

|

|

Nuclear import factors (importin-α7 and Rch1)

|

p300/CBP

|

References

[1] Adrian Drazica, Line M.Myklebust, et al. The world of protein acetylation [J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics

Volume 1864, Issue 10, October 2016, Pages 1372-1401.

[2] David G. Christensen, Xueshu Xie, et al. Post-translational Protein Acetylation: An Elegant Mechanism for Bacteria to Dynamically Regulate

Metabolic Functions [J]. Front Microbiol. 2019; 10: 1604.

[3] Ibraheem Ali, Ryan J. Conrad, et al. Lysine Acetylation Goes Global: From Epigenetics to Metabolism and Therapeutics [J]. Chem Rev. Author

manuscript; available in PMC 2019 Jul 3.

[4] Miao-Miao Wang, Di You & Bang-Ce Ye. Site-specific and kinetic characterization of enzymatic and nonenzymatic protein acetylation in bacteria [J].

Sci Rep 7, 14790 (2017).

[5] Hollebeke J, Van Damme P and Gevaert K: N-terminal acetylation and other functions of Nalpha-acetyltransferases [J]. Biol Chem. 393:291–298.

2012.

[6] Yang XJ and Gregoire S. Metabolism, cytoskeleton and cellular signalling in the grip of protein Nepsilon- and O-acetylation [J]. EMBO Rep. 8:556–562.

2007.

[7] Song L, Wang G, et al. Reversible acetylation on Lys501 regulates the activity of RNase II [J]. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1979–1988.

[8] Narita T, Weinert BT, et al. Functions and mechanisms of non-histone protein acetylation [J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:156–174.

[9] Jie Ouyang, Zhenhua Zeng, et al. SIRT3 Inactivation Promotes Acute Kidney Injury Through Elevated Acetylation of SOD2 and p53 [J]. J Surg

Res. 2019 Jan;233:221-230.

[10] Can Xia, Yu Tao, et al. Protein acetylation and deacetylation: An important regulatory modification in gene transcription (Review) [J]. Exp Ther

Med. 2020 Oct; 20(4): 2923–2940.

[11] MingjieYang, YingmeiZhang, et al. Acetylation in cardiovascular diseases: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications [J]. Biochimica et

Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease Volume 1866, Issue 10, 1 October 2020, 165836.

[12] Hu M, Zhang Q, et al. lncRNA CCAT1 is a biomarker for the proliferation and drug resistance of esophageal cancer via the miR-

143/PLK1/BUBR1 axis [J]. Mol Carcinog. 2019;58:2207–2217.

[13] Li J and Qi Y. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits cell growth, migration and invasion in Caco-2 cells by downregulation of lncRNA CCAT1 [J]. Exp Mol Pathol.

2019;106:131–138.

[14] Zhang E, Han L, et al. H3K27 acetylation activated-long non-coding RNA CCAT1 affects cell proliferation and migration by regulating SPRY4

and HOXB13 expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [J]. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3086–3101.

[15] Hu H, Zhu W, et al. Acetylation of PGK1 promotes liver cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis [J]. Hepatology. 2017;65:515–528.

[16] Hosp F, Lassowskat I, et al. Lysine acetylation in mitochondria: from inventory to function [J]. Mitochondrion 2017. 33:58–71.

[17] Soppa J. Protein acetylation in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes [J]. Archaea 2010:820681.

CUSABIO team. Protein Acetylation: An Important Post-translational Modification in Eukaryotic Cells. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21024.html

Comments

Leave a Comment