Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was initially described by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot in 1869, but its recognition significantly increased in the United States when it forced the retirement of the renowned baseball player Lou Gehrig in 1939. For an extended period, ALS was widely known as Lou Gehrig's Disease.

2. Risk Factors of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

The cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is still unknown. It may be related to heredity and genetic defects [4]. In addition, some environmental factors, such as heavy metal poisoning, may cause damage.

2.1 Genetic Factors

Progress in molecular genetic techniques has unveiled over 120 potential disease-modifying or pathogenic genes for ALS. Notably, SOD1, TARDBP, fused in sarcoma/translated in liposarcoma (FUS/TLS), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) demonstrate the highest frequency of pathogenic variants, with other genes carrying such variants being relatively uncommon [5].

|

ALS locus number

|

Gene/Encoded Protein

|

Inheritance

|

Protein function: disease mechanisms

|

|

ALS1

|

SOD1/Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase

|

AD (AR)

|

Dismutates superoxide free radicals: oxidative stress; protein aggregation; mitochondrial dysfunction; axonal transport defects; proteasome impairment; glial dysfunction

|

|

ALS2

|

ALS2/Alsin

|

AR

|

Intracellular trafficking

|

|

ALS4

|

SETX/Senataxin

|

AD

|

RNA processing

|

|

ALS5

|

SPG11/Spatacsin

|

AR

|

Vesicle trafficking; axonal defects

|

|

ALS6

|

FUS/Fused in sarcoma RNA binding protein

|

AD (AR)

|

RNA processing; DNA damage repair defects; nucleocytoplasmic transport defects; stress granule function; protein aggregation

|

|

ALS8

|

VAPB/Vesicle-associated membrane protein

|

AD

|

Proteasome impairment; intracellular trafficking

|

|

ALS9

|

ANG/Angiogenin

|

AD

|

RNA processing

|

|

ALS10

|

TARDBP/TDP-43

|

AD

|

RNA processing; nucleocytoplasmic transport defects; stress granule function; protein aggregation

|

|

ALS11

|

FIG4/Polyphosphoinositide phosphatase

|

AD

|

Intracellular trafficking

|

|

ALS12

|

OPTN/Optineurin

|

AD (AR)

|

Autophagy; protein aggregation; inflammation; NF-κB regulation; membrane trafficking; exocytosis; vesicle transport; reorganization of actin and microtubules; cell cycle control

|

|

ALS13

|

ATXN2/Ataxin 2

|

AD

|

RNA processing

|

|

ALS14

|

VCP/Valosin-containing protein/ Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase

|

AD/de novo

|

Autophagy; proteasome impairment; defects in stress granules; protein aggregation; mitochondrial dysfunction; endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction

|

|

ALS15

|

UBQLN2/Ubiquilin 2

|

X-linked AD

|

Proteasome impairment; autophagy; protein aggregation; oxidative stress; axonal defects

|

|

ALS16

|

SIGMAR1/Sigma non-opioid intracellular receptor 1

|

AD and AR

|

Proteasome impairment; intracellular trafficking

|

|

ALS17

|

CHMP2B/Charged multivesicular body protein 2b

|

AD

|

Autophagy; protein aggregation

|

|

ALS18

|

PFN1/Profilin-1

|

AD

|

Axonal defects

|

|

ALS19

|

ERBB4/Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-4

|

AD

|

Neuronal development

|

|

ALS20

|

hnRNPA1/Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1

|

AD/de novo risk factor

|

RNA processing

|

|

ALS21

|

MATR3/Matrin-3

|

AD

|

RNA processing

|

|

ALS22

|

TUBA4A/Tubulin α4A chain

|

AD

|

Cytoskeleton

|

|

ALS23

|

ANXA11/Annexin A11

|

AD

|

Intracellular trafficking

|

|

ALS24

|

NEK1

|

AD

|

Intracellular trafficking; DNA-damage response; microtubule stability

|

|

ALS25

|

KIF5A/Kinesin heavy chain isoform 5A

|

AD

|

Axonal defects; intracellular trafficking

|

|

ALS-new

|

GLT8D1/Glycosyltransferase 8 domain-containing protein 1

|

AD

|

Ganglioside synthesis

|

|

ALS-new

|

TIA1/Cytotoxic granule-associated RNA-binding protein

|

AD

|

Delayed stress granule disassembly; stress granule accumulation

|

|

ALS-new

|

C21orf2/Cilia and flagella-associated protein 410

|

AD

|

Microtubule assembly; DNA damage response and repair; mitochondrial function; interacts with NEK1

|

|

ALS-new

|

DNAJC7/DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C7

|

Unknown

|

Protein homeostasis; protein folding and clearance of degraded proteins; protein aggregation

|

|

ALS-new

|

LGALSL/Galectin-related protein

|

Unknown

|

Unknown

|

|

ALS-new

|

KANK1/KN motif and ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 1

|

Unknown

|

Cytoskeleton; axonopathy

|

|

ALS-new

|

CAV1/Caveolin 1

|

Unknown

|

Intracellular and neurotrophic signalling

|

|

ALS-new

|

SPTLC1/Serine palmitoyltransferase, long-chain base subunit 1

|

AD

|

Excess sphingolipid biosynthesis

|

|

ALS-new

|

ACSL5/Long-chain fatty acid coenzyme A ligase 5

|

Unknown

|

Long-chain fatty acid metabolism

|

|

ALS-putative

|

ELP3/Elongator protein 3

|

Unknown

|

Ribostasis; cytoskeletal integrity

|

|

ALS-putative

|

DCTN1/Dynactin subunit 1

|

AD

|

Axonal transport

|

|

ALS-putative

|

PARK9/Probable cation-transporting ATPase 13A2

|

AR

|

Lysosome function

|

|

FTD-ALS1

|

C9orf72/Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72

|

AD

|

RNA processing; nucleocytoplasmic transport defects; proteasome impairment; autophagy; inflammation; protein aggregation (DPRs)

|

|

FTD-ALS2

|

CHCHD10/Coiled-coil–helix-coiled–coil-helix domain-containing protein 10

|

AD

|

Mitochondrial function; synaptic dysfunction

|

|

FTD-ALS3

|

SQSTM1/Sequestosome-1

|

AD

|

Proteasome impairment; autophagy; protein aggregation; axonal defects; oxidative stress

|

|

FTD-ALS4

|

TBK1/Serine–threonine protein kinase

|

AD

|

Autophagy; inflammation; mitochondrial dysfunction

|

|

FTD-ALS5

|

CCNF/Cyclin F

|

AD

|

Autophagy; axonal defects; protein aggregation

|

Table 1. Genes identified as causative in or increasing the risk of ALS

This Table information is sourced from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41573-022-00612-2

2.2 Environmental Factors

Environmental factors also play an important role in the pathogenesis of ALS [6]. Possible influencing factors include exposure to toxic or infectious pathogens, viruses, physical trauma, diet, and behavior and occupational factors.

Toxic substances: heavy metal poisoning such as lead (Pb) and manganese (Mn).

Excitations of excitotoxic amino acids and free radicals resulted in the death of motor neurons.

Researchers suggest that exposure to lead, pesticides, and other environmental toxins during war or intense physical activity may be the cause of increased risk of ALS in some veterans and athletes.

As a complex disease, both genetic and environmental factors play an important role in the occurrence and development of ALS.

2.3 Other Risk Factors

ALS is also associated with several potential risk factors:

-

Age: Although it also occurs in young people, even children, and very old people, ALS has a peak onset age of 50 to 75 years old with sporadic disease of 58 to 63 years old, and familial disease of 47 to 52 years old, and the incidence is rapidly decreasing after age 80.

-

Gender: Men are slightly more likely to develop ALS than women. Studies have shown that overall, the ratio of men to women with the disease is about 1.5.

-

Race and ethnicity: Caucasian and non-Hispanic are most likely to have ALS. Research shows the incidence of ALS may be lower among African, Asian, and Hispanic ethnicities than among whites.

3. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

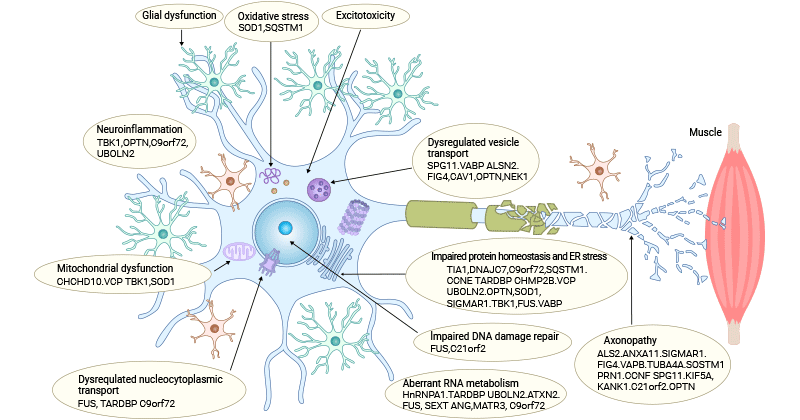

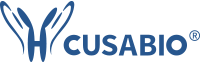

Despite years of research, the precise pathogenic mechanisms of ALS remain unknown, the disease's pathophysiological mechanisms likely result from the intricate interplay among molecular and genetic pathways. Scientists have proposed numerous pathogenic mechanisms as follows:

Figure 1. Pathogenesis of ALS

This picture is sourced from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41573-022-00612-2

3.1 Glutamate Excitotoxicity

Increased release of glutamate from synapses or inadequate reuptake from the synaptic cleft results in heightened extracellular glutamate levels, directly leading to overactivation of the glutamate receptors including AMPARs and NMDARs [4]. Excessive glutamatergic input eliciting excitotoxicity causes cortical hyperexcitability and dysfunction in ALS patients.

GLAST and GLT-1, along with their astrocytic counterparts EAAT1 and EAAT2 of astrocytes, are responsible for absorbing synaptic glutamate to maintain optimal extracellular levels, blocking the buildup of glutamate in the synaptic cleft and consequent excitotoxicity [7]. The dysregulation of these glutamate transporters in glial cells could be a key contributor to excitotoxicity and its associated neuropathogenesis.

Additionally, the excessive stimulation of glutamate receptors triggers an elevation in cytoplasmic Ca2+, which leads to an increased intracellular Ca2+ influx and accumulation, a crucial factor in excitotoxicity.

3.2 Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inadequate compensatory antioxidant systems [8,9]. In ALS, there are many ROS-producing processes, which are interconnected, creating a cycle that exacerbates oxidative damage.

Impaired mitochondrial function can lead to the leakage of electrons during the electron transport chain, resulting in the generation of ROS [10,11]. During glutamate excitotoxicity, ROS is also generated as the byproduct [12]. Abnormal calcium levels can activate enzymes, such as NADPH oxidase, that produce ROS. The presence of aggregated proteins, such as TDP-43 and FUS, contributes to oxidative damage. Aberrant RNA processing can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production. Inflammatory cells, such as microglia and astrocytes, release ROS as part of their immune response to the disease. Calcium dysregulation is closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

Mutations in antioxidant enzymes, particularly superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) [13], are associated with some cases of familial ALS. Dysfunction in these enzymes reduces the cell's ability to neutralize ROS, contributing to oxidative stress.

ROS plays a substantial role in the degeneration of neuronal cells by influencing the function of biomolecules such as DNA, RNA, lipids, and proteins, and processes like nucleic acid oxidation and lipid peroxidation.

Many oxygen-dependent cell functions, such as signal transduction, gene transcription, oxidative phosphorylation, and mitochondrial ATP generation, also produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2•−), or hydroxyl radical (HO•) through redox reactions.

Free oxygen radicals gradually impair proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, leading to compromised cellular processes, inflammation, and eventual cell death.

3.3 Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria are important to neurons not only for their well-known role as ATP producer through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) but also for their involvement in phospholipid biogenesis, calcium homeostasis, apoptosis, and other biological processes. Mitochondria play a crucial role as calcium buffering organelles in neurons, regulating local calcium dynamics to, for instance, control neurotransmitter release.

Mitochondrial morphology abnormalities, elevated ROS production, deficiencies in mitochondrial dynamics, damaged axonal transport, and disruption of mitochondrial-associated membranes (MAM) integrity have been observed in ALS patients. Impaired mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) function leads to diminished production of ATP, and compromised OXPHOS can also yield high levels of ROS that further accelerate mitochondrial damage and culminate in neuronal death.

Genes associated with mitochondria, such as SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, C9orf72, and CHCHD10, are mutated in ALS patients. SOD1 mutations compromise the mitochondria's capacity to clear ROS. TDP-43 mutated isoforms interfere with mitochondrial RNA expression and FUS mutant isoforms interact with the catalytic subunits of the mitochondrial ATP synthase, leading to aberrant mitochondrial membrane potential, reducing ATP generation, and impacting oxygen consumption. C9orf72 mutations elevate neuronal Ca2+ influx concentration and the polyGR overexpression that induces mitochondrial dysfunction by changing protein binding patterns on mitochondria.

3.4 Imbalance of Protein Homeostasis and Aberrant RNA metabolism

The cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) and RNA metabolism (ribostasis) play an essential role in maintaining the structure and function of the brain. Yet, disruptions in proteostasis and ribostasis occur due to aging, cellular stress, and genetic factors, resulting in protein misfolding, deposition of insoluble aggregates, and abnormal dynamics of ribonucleoprotein granules.

Ample evidence supports the involvement of protein misfolding and aggregation in the development and progression of ALS. ALS patients exhibit the independent deposition of three main types of pathogenic aggregates in motor neurons. Approximately of 97% ALS patients have TDP-43, SOD1, and FUS positive inclusion bodies were detected in 97%, 2%, and 1% of ALS patients, respectively [14].

Mutations in genes like SOD1, C9orf72, TDP-43, ubiquilin-2, and VCP disrupt the UPS and autophagy degradation pathways, causing the aberrant buildup of toxic proteins subsequently resulting in proteostasis imbalance and ultimately triggering cell death.

3.5 Nucleocytoplasmic Transport Detects

Nucleocytoplasmic transport, crucial for the regulated movement of molecules between the cell nucleus and cytoplasm, is disrupted in ALS due to mutations in genes such as C9orf72 and FUS [15]. These mutations affect nuclear pore complexes and nucleocytoplasmic transport, leading to the mislocalization of RNA-binding proteins like TDP-43. Aberrant accumulation of TDP-43 in the cytoplasm is a pathological hallmark of ALS.

Dysregulated nucleocytoplasmic transport contributes to the aggregation of misfolded proteins, RNA metabolism abnormalities, and impaired cellular homeostasis, ultimately contributing to the degeneration of motor neurons in ALS.

3.6 DNA Damage and Impaired DNA Repair

DNA damage is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of ALS. Motor neurons, the primary cells affected in ALS, are particularly vulnerable to DNA damage due to their post-mitotic nature and high metabolic activity. Various mechanisms can induce DNA damage in ALS, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impairment of DNA repair pathways. Accumulation of DNA damage can lead to genomic instability, cell cycle abnormalities, and activation of cell death pathways. Additionally, mutations in genes involved in DNA repair processes, such as C9orf72 [16] and FUS [17], have been implicated in ALS.

3.7 Neuroinflammation

The pathophysiology of ALS is closely linked to neuroinflammatory processes, involving the release of factors that can be either neuroprotective or neurotoxic, contributing to motor neuron pathology [18].

Microglia and astrocytes are activated in response to the damage and stress associated with ALS and then release pro-inflammatory molecules, including cytokines and chemokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which can amplify the immune response and contribute to neuronal damage. The infiltration of peripheral immune cells such as T lymphocytes and activation of the NF-κB pathway also cause neuroinflammation.

Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress are interconnected in ALS. Inflammatory mediators released by activated glial cells can induce oxidative stress, and conversely, oxidative stress can activate inflammatory pathways, creating a self-perpetuating inflammatory cycle. Dysregulated blood-brain barrier and mutant protein interactions further exacerbate neuroinflammation, leading to motor neuron damage and disease progression in ALS.

3.8 Oligodendrocyte dysfunction

Oligodendrocytes are glial cells responsible for myelinating axons, ensuring efficient neuronal signaling. Pathological inclusions, myelin abnormalities, demyelination, and even oligodendrocyte degeneration are observed in the gray matter of the ventral spinal cord of individuals with ALS [19,20].

Moreover, mutations in ALS-associated genes like SOD1, FUS, and TDP-43 adversely affect oligodendrocytes, triggering the formation of protein aggregates, inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress, and ultimately resulting in apoptosis [20]. Significant evidence suggests that activated microglia and astrocytes exert cytotoxic effects on oligodendrocytes and their precursor cells. Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and oxidative stress are also causes of the oligodendrocyte degeneration.

3.9 Axonal Transport Disruption

Axonal transport is a constitutive process essential for sustaining neuron survival. Impaired axonal transport is underscored as a pathogenic mechanism, given that mutations in genes controlling various motor proteins, such as KIF5A, DCTN1, and DYNC1H1, are implicated in ALS [21,22]. Mutations in SOD1, FUS, and TDP-43 also change axonal transport.

In addition to the mutations in genes encoding axonal transport-associated proteins, axonal transport defects participating in the pathogenesis of ALS may also involve several processes, including disrupted microtubule stability [23], hyperphosphorylation of motor proteins [24], and weakened associations between cargoes and motor proteins.

5. Latest Research on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

On the one hand, scientists are studying ALS-associated genetic variants. Earlier studies focused on finding a link between variations in a single gene and this disease. As technology continues to advance, scientists can now look more accurately at the entire genome, leading to some interesting discoveries, such as the discovery of variations in the C9ORF72 gene.

On the other hand, researchers are studying how neurons die. Neuronal death is one of the hallmarks of ALS, but little is known about this process. However, some new research is shedding light on the mechanisms by which neurons die, which may help to develop better treatments.

Currently, attempts are being made internationally to use neurotrophic factors, antioxidants such as vitamin E and vitamin C, as well as creatine, CoQ10, etc. in combination with Rilutek to provide protective treatment for ALS. However, the above treatments have yet to be proven in clinical trials.

Some studies are also exploring different therapies, such as gene therapy and immunotherapy. The idea of gene therapy is to introduce artificially modified genes into the body to repair or replace the damaged ones. Immunotherapy aims to harness the body's immune system to recognize and attack the cells that cause muscular dystrophy. While these approaches are still in the early stages of research, they may shed light on future treatments.

In summary, ALS is a fatal paralytic neurodegenerative disease affecting both upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in progressive weakness, spasticity, and hyperreflexia. Death typically ensues 2-5 years after symptom onset, primarily due to respiratory failure resulting from weakened respiratory muscles. As of now, there is no cure or effective treatment for ALS, although certain medications are employed to alleviate symptoms. However, multiple ALS-associated genes have been identified, and investigating these genes and their involved processes may provide strategies for ALS treatment.

References

[1] Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; et al. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [J]. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17085.

[2] Manjaly, Z.R.; Scott, K.M.; et al. The Sex Ratio in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Population Based Study [J]. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 439–442.

[3] Byrne S, Walsh C, Lynch C, et al. Rate of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2011, 82(6):623-627.

[4] Duan QQ, Jiang Z, et al. Risk factors of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a global meta-summary. Front Neurosci [J]. 2023 Apr 24;17:1177431.

[5] Boylan K (2015). Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [J]. Neurol Clin 33:807–830.

[6] Ahmed A, Wicklund M P. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: What Role Does Environment Play? [J]. Neurologic Clinics, 2011, 29(3):689-711.

[7] Pajarillo, E., Rizor, A., et al. (2019). The role of astrocytic glutamate transporters GLT-1 and GLAST in neurological disorders: potential targets for neurotherapeutics [J]. Neuropharmacology 161:107559.

[8] Cunha-Oliveira T., Montezinho L., et al. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Pathophysiology and Opportunities for Pharmacological Intervention [J]. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020;15:5021694.

[9] Motataianu A, Serban G, Barcutean L, Balasa R. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Synergy of Genetic and Environmental Factors [J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Aug 19;23(16):9339.

[10] Kausar S., Wang F., Cui H. The Role of Mitochondria in Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Its Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases [J]. Cells. 2018;7:274.

[11] Greco V., Longone P., et al. Crosstalk Between Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage: Focus on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [J]. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019;1158:71–82.

[12] Olloquequi, J., Cornejo-Córdova, E., et al. (2018). Excitotoxicity in the pathogenesis of neurological and psychiatric disorders: therapeutic implications [J]. J. Psychopharmacol. 32, 265–275.

[13] Higgins C.M., Jung C., et al. Mutant Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase that causes motoneuron degeneration is present in mitochondria in the CNS [J]. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:RC215.

[14] Ling SC, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis [J]. Neuron 2013;79:416–438.

[15] Vanneste J, Van Den Bosch L. The Role of Nucleocytoplasmic Transport Defects in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Nov 10;22(22):12175.

[16] Balendra R, Isaacs AM. C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD: multiple pathways to disease [J]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:544–558.

[17] Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobágyi T, et al. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6 [J]. Science. 2009;323:1208–1211.

[18] Fritz E, Izaurieta P, et al. Mutant SOD1-expressing astrocytes release toxic factors that trigger motoneuron death by inducing hyperexcitability [J]. J Neurophysiol. 2013;109(11):2803–14.

[19] Kang SH, Li Y, Fukaya M, et al. Degeneration and impaired regeneration of gray matter oligodendrocytes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [J]. Nat. Neurosci. 16(5), 571–579 (2013).

[20] Annelies Nonneman , Wim Robberecht, Ludo Van Den Bosch. The role of oligodendroglial dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [J]. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4(3):223-39.

[21] Nicolas A, et al. Genome-wide analyses identify KIF5A as a novel ALS gene [J]. Neuron. 2018;97(6):1268–1283.

[22] Munch C, et al. Point mutations of the p150 subunit of dynactin (DCTN1) gene in ALS [J]. Neurology. 2004;63(4):724–726.

[23] Godena, V. K., Brookes-Hocking, et al. (2014). Increasing microtubule acetylation rescues axonal transport and locomotor deficits caused by LRRK2 roc-COR domain mutations [J]. Nat. Commun. 5:5245.

[24] Morfini, G. A., Bosco, D. A., et al. (2013). Inhibition of fast axonal transport by pathogenic SOD1 involves activation of p38 MAP kinase [J]. PLoS One 8:e65235.

Comments

Leave a Comment