Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are stem cells derived from the undifferentiated inner mass cells of a human embryo. Self-renewal and pluripotency are two distinctive characteristics of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which enable ESCs to keep their own stemness and to differentiate into multiple lineages. ESCs can be induced to differentiate into almost all cell types in the body, both in vitro and in vivo.

In terms of these characteristics, ESCs have extremely broad application prospects in clinic. But, the primary problem that must be solved is how the embryonic stem cells achieve self-renewal and directed differentiation before applied to the clinic successfully. Since Evans and Kaufman separated mouse ESCs for the first time in 1981, ESCs have been a hotspot in research.

Nanog is a homeobox transcription factor discovered in May 2003. It is a critical factor that contributes to the self-renewal of ESCs. It is thought to play a key role in the maintenance of pluripotency of ESCs. The expression of Nanog in undifferentiated ESCs is higher than in differentiated ESCs. It plays a very important role in maintaining the versatility of early embryonic embryonic embryos and preventing their differentiation into endoderm. Over the past decade, many research advances have been made in Nanog structure, function, mechanism, and related diseases.

1. What is The Structure of Nanog?

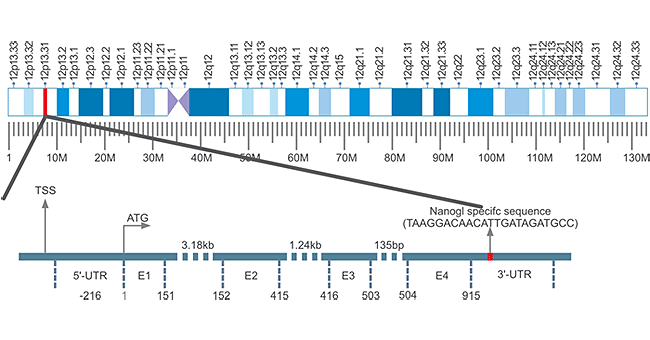

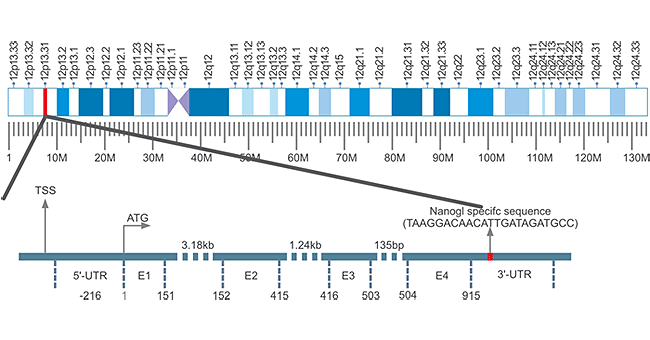

At present, most of the Nanog genes are studied in mouse and human Nanog genes. Here we focus on the Nanog gene in human. Human Nanog gene, also known as Nanog1 (Gene ID: 13376297), is localized on chromosome 12 and consists of 4 exons and 3 introns with a 915 bp open reading frame (ORF) (Fig. 1) [1]. It is very unique that Nanog1 gene has been tandem duplicated into a variant gene Nanog2 (NanogP1), as well as many pseudogenes (NanogP2-P11) during evolution [2] [3]. The comparison of human and chimpanzee genome sequences has revealed that Nanog2 retained its intronic sequences, while NanogP2 to P11 are dispersed, intronless and reversely transcribed integrant [4].

Figure 1. The Structure of Nanog Gene

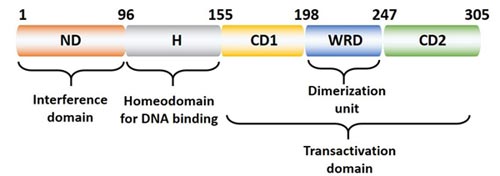

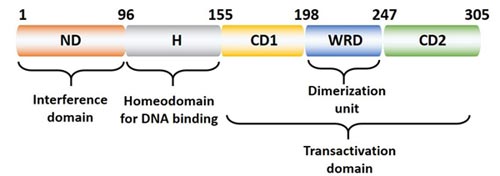

The human Nanog protein is encoded by the Nanog1 gene and contains 305 amino acids with highly conserved DNA homology binding domain. The Nanog1 protein structure can be roughly divided into three regions (Figure 2), the N-terminal "interfering" domain (ND), the DNA homologous domain (H), and the C-terminal transcriptional activation domain.

The H domain contains 60 amino acid residues that interact with proteins (such as Oct4) and bind to DNA; the ND domain has 95 serine- and threon-rich residues, and acidic residues are found in trans-activators. The C-terminal domain is composed of 150 amino acid residues with no obvious transcriptional activation motif, and this domain includes two subdomains (CD1 and CD2 are responsible for transactivation) and a tryptophan-rich domain (WRD) is involved in dimerization. [5].

Figure 2. The Structure of Nanog Protein

2. What is The Function of Nanog?

Nanog is mainly expressed in the inner cell mass (ICM) of blastocysts [6]. Accumulating studies have shown that Nanog gene expression is closely related to cell division and differentiation and stem cell characteristics of cells [7] [8]. The Nanog gene is highly expressed in the cells with strong ability of division, and the expression of the Nanog gene gradually decreases with cell differentiation until it is not expressed in the fully differentiated cells.

Therefore, in-depth study of the expression of Nanog in adult tissues is conducive to understanding the molecular biological characteristics of adult stem cells and their mechanisms of division and differentiation.

As mentioned before, Nanog is a new gene that was officially identified and named in 2003. It plays an important role in the regulation of cell fate in the inner cell mass during embryonic development. It maintains the pluripotency of the ectoderm and prevents its differentiation like primitive endoderm.

In addition to maintaining the self-renewal and pluripotency of ESCs, Nanog can also regulate the cell cycle of ESCs. Related reports indicate that ESCs clones with overexpressed Nanog accelerate S phase entry [9]. In addition, another function of Nanog plays an important role in the development of tumors and can be used as a diagnostic marker for tumors. These two functions will be elaborated in the mechanism of action by the relationship with ESCs and cancer stem cells (ESCs), respectively.

3. The Mechanism of Nanog

NANOG is critical in stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency maintenance and tumorigenesis. Here, we describe these two mechanisms from the role of NANOG in stem cells and cancer stem cells and the associated interaction proteins.

3.1 The Mechanism of Nanog in ESCs

ESCs are pluripotent cells derived from ICM (internal cell mass) of blastocyst stage embryos. The cell has two obvious characteristics: unlimited self-renewal and pluripotency. The self-renewal and pluripotency of ESCs are controlled by a variety of transcription factors, the most common of which are Nanog, Oct4 and SOX2. In this section we focus on the regulation of NANOG expression in ESCs.

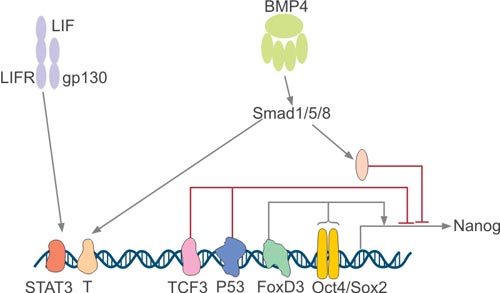

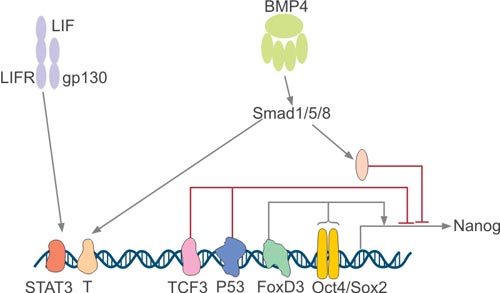

Nanog expression is regulated only in pluripotent cells, and Nanog expression is down-regulated after pluripotent cell differentiation. Guangjin Pan et al. found that a composite Oct4/Sox2 motif localized -180 bp upstream of the transcription start site plays an important role in Nanog regulation by analyzing its 5' promoter region (Figure 3) [10] [11].

The Nanog proximal promoter containing the Oct4/Sox2 motif drives the reporter gene to recapitulate appropriate Nanog expression in pluripotent and non-pluripotent cells, and this motif is highly conserved between mouse, rat and human. Although high expression of Nanog is beneficial for self-renewal of ESCs, overexpression of Oct4 induces differentiation.

FoxD3, also known as a forkhead family transcription factor, is highly expressed in mouse ESCs and pluripotent cells of early embryos [12]. It has been reported that FoxD3 can activate the Nanog promoter via an ES cell-specific enhancer localized at -270 upstream of the transcription start site [13]. Initially, FoxD3 was called a transcriptional repressor, but it still activates Nanog transcription, suggesting that the genetic environment can determine FoxD3 regulation.

Functionally, Nanog can inhibit differentiation, and it is necessary to down-regulate Nanog to promote differentiation during embryonic development. As shown in Figure 3, the tumor suppressor p53 binds to the Nanog promoter and downregulates Nanog during ESC differentiation. However, when p53-/-ESC was treated with retinoic acid (RA), Nanog was nevertheless down-regulated during differentiation [14]. This result indicates that there are certainly other regulatory factors involved in suppressing Nanog during ESC differentiation. Tcf3 is a transcription factor that acts downstream of the Wnt pathway and is highly expressed in undifferentiated mouse ESCs. Tcf3 knockdown in mouse ESCs can cause delayed differentiation and upregulate Nanog [15].

Figure 3. Regulation of Nanog Expression

3.2 The Mechanism of Nanog in tumor

Since the first discovery of cancer stem cells (CSCs) in acute myeloid leukemia, our understanding of cancer has been fundamentally changed [16]. CSCs refer to cancer cells with stem cell properties, including "self-replication" and "multi-cell differentiation." Usually such cells are thought to have the potential to form tumors and develop into cancer, especially as the cancer is transferred out, producing an origin of new cancers.

A large amount of studies have confirmed that NanogP8, a Nanog1 homolog in tumor cells, plays a key role in regulating CSC properties. Overexpression of NANOG in tumor cells can affect some important cancer phenotypes through related signaling pathways, including cell proliferation, cell migration and invasion, chemo-resistance, and hypoxic stress.

As shown in Figure 4, NANOG can be activated by multiple stimuli in malignant tumors. Hypoxic activates NANOG through the actions of HIF-1α or HIF-2α signaling pathways [17]. STAT3, as a downstream target of NANOG, plays an important role in NANOG-mediated immune evasion, epithelial mesenchymal transition and chemo-resistance. Moreover, NANOG is also able to regulate resistance to CTL-mediated lysis and Treg cells recruitment by activating Akt and TGF-β1 [18]. In addition, NANOG regulates chemo-resistance by upregulating MDR-1, IGF2BP3, and YAP1 [19]. NANOG can also affect multiple cell cycle regulators, of which cyclin D1 has been shown to be directly regulated by NANOG [20].

Figure 4. NANOG signaling pathways in human malignancies

4. NANOG and Cance

As mentioned earlier, Nanog is not only a key factor in maintaining ESCs self-proliferation, but also has a simple relationship with tumors. Because CSCs, like ESCs, have the ability to self-proliferate and have multiple identical signaling pathways. Based on these features, the researchers speculate that in-depth study of the regulation mechanism of Nanog gene expression will help to explore new ways to control and treat cancer [21].

At present, a number of studies have confirmed that Nanog has different expression levels in various epithelial-derived tumor cells. In vitro experiments of cultured tumor cells, the expression of Nanog in tumors is higher than normal tissues. Nanog is specifically expressed in embryonal tumor cells, teratoma tissue, testicular carcinoma in situ, and seminoma, whereas no Nanog expression is found in normal testes [22].

Siu et al. found that the expression level of Nanog in choriocarcinoma cells was significantly higher than normal placenta. And interfered Nanog expression resulted in increased JEG-3 cells apoptosis [23]. Nanog was also found in somatic tumors such as breast cancer, glioma, bladder cancer, lung cancer and human sarcoma cell lines. The higher the tumor differentiation level, the stronger the expression.

In addition, silencing the Nanog gene can retard cell cycle, inhibit tumor development and induce tumor cell differentiation [24]. These results fully demonstrate that the expression of Nanog gene is closely related to the state of tumor differentiation, and plays an important role in promoting the development of tumor cells and anti-apoptosis, and can be used as a promising marker for cell pluripotency and tumor diagnosis.

References

[1] Chang DF, Tsai SC, et al. Molecular characterization of the human NANOG protein [J]. Stem Cells. 2009, 27: 812–821.

[2] Eberle I, Pless B, et al. Transcriptional properties of human NANOG1 and NANOG2 in acute leukemic cells [J]. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38:5384–5395.

[3] Scerbo P, Markov GV, et al. On the origin and evolutionary history of NANOG [J]. PLoS One. 2014, 9: e85104.

[4] Wei Zhang, Yi Sui. Insights into the Nanog gene: A propeller for stemness in primitive stem cells [J]. 2016, 12(11): 1372-1381.

[5] GUANG JP, DUAN QP. Identification of Two Distinct Transacti-vation Domains in the Pluripotency Sustaining Factor Nanog [J]. Cell Research. 2003, 13(6):499-502.

[6] Anmstrong L, Hughes O, et al. The role of PBK/AKT, MAPK/ERK and NF-κβ signaling in the maintenance of human embryonic stem cell pluripotency and viability highlighted by transcriptional profiling and functional analysis [J]. Hum Mol Cenet. 2006, 15(11):1894-1913.

[7] Yu J, Vodyanik MA, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells [J]. Science. 2007, 318(5858): 1917-1920.

[8] Hart AH, Hanley L, et al. The pluripotency homeobox gene NANOG is expressed in human germ cell tumors [J]. Cancer. 2005, 104(10): 2092-2098.

[9] Zhang X, Neganova I, et al. A role for NANOG in G1 to S transition in human embryonic stem cells through direct binding of CDK6 and CDC25A [J]. J Cell Biol. 2009, 184: 67–82.

[10] Rodda DJ, Chew JL, et al. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2 [J]. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280:24731-24737.

[11] Guangjin Pan1, James A Thomson. Nanog and transcriptional networks in embryonic stem cell pluripotency [J]. Cell Research. 2007, 17:42-49.

[12] Sutton J, Costa R, et al. Genesis, a winged helix transcriptional repressor with expression restricted to embryonic stem cells [J]. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271:23126-23123.

[13] Pan G, Li J, et al. A negative feedback loop of transcription factors that controls stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal [J]. FASEB J. 2006, 20:1730-1732.

[14] Lin T, Chao C, et al. p53 induces differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells by suppressing Nanog expression [J]. Nat Cell Biol. 2005, 7:165-171.

[15] Pereira L, Yi F, et al. Repression of Nanog gene transcription by Tcf3 limits embryonic stem cell self-renewal [J]. Mol Cell Biol 2006.

[16] Hope KJ, Jin L, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia originates from a hierarchy of leukemic stem cell classes that differ in self-renewal capacity [J]. Nat Immunol. 2004, 5:738-743.

[17] Oscar GW Wong and Annie NY Cheung. Stem cell transcription factor NANOG in cancers – is eternal youth a curse [J]? Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2015, 1744-7631.

[18] Hasmim M, Noman MZ, et al. Cutting edge: hypoxia-induced Nanog favors the intratumoral infiltration of regulatory T cells and macrophages via direct regulation of TGF-beta1 [J]. J Immunol.

2013, 191:5802–5806.

[19] Yang L, Zhang X, et al. Increased Nanog expression promotes tumor development and cisplatin resistance in human esophageal cancer cells [J]. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012, 30:943–952.

[20] Han J, Zhang F, et al. RNA interference-mediated silencing of NANOG reduces cell proliferation and induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells [J]. Cancer Lett. 2012, 321:80–88.

[21] Chambers I, Silva J, et al. Nanog safegurads pluripotency and mediates germline development [J]. Nature. 2007, 450(7173): 1230-1234.

[22] Hoei-Hansen CE, Sehested A, et al. New evidence for the origin of intracranial germ cell tumours from primordial germ cells: expression of pluripotency and cell differentiation markers [J]. J Pathol. 2006, 2019(1): 25-33.

[23] Siu MK, Wong ES, et al. Overexpression of NANOG in gestational trophoblastic diseases: effect on apoptosis, cell invasion, and clinical outcome [J]. Am J Pathol. 2008, 173(4): 1165-1172.

[24] Fujii H, Honoki K, et al. Sphere-forming stem-like cell populations with drug resistance in human sarcoma cell line [J]. Int J Oncol. 2009, 34(5): 1381-1386.

CUSABIO team. Homeobox Transcription Factor- NANOG. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20967.html

Comments

Leave a Comment