With the progress of science and medicine, antibodies have become potent tools to recognize, detect, isolate, or visualize their corresponding antigens in basic science research and clinical assays. Whether antibodies work and are stable and reliable in experiments is critical to researchers, clinical users, antibody manufacturers, and journal publishers. It has been reported that ample antibody-based research failed to meet expectations. Therefore, it is necessary to perform functional verification of antibodies to ensure their quality.

This article mainly focuses on antibody validation, which will be elaborated on several aspects, including the definition, significance, methods of antibody validation, and their comparison.

3. How to Validate An Antibody?

The assessment of antibody validation is based on several factors, including the characterization of antibodies and antigens, binding specificity and selectivity, concentrations of antibodies and additives, documentation, affinity constant, influence of non-target substances, stabilization and storage, application protocols, and user feedback [1].

Antibody validation should minimally include four main criteria: binding specificity, affinity, selectivity, and reproducibility [2].

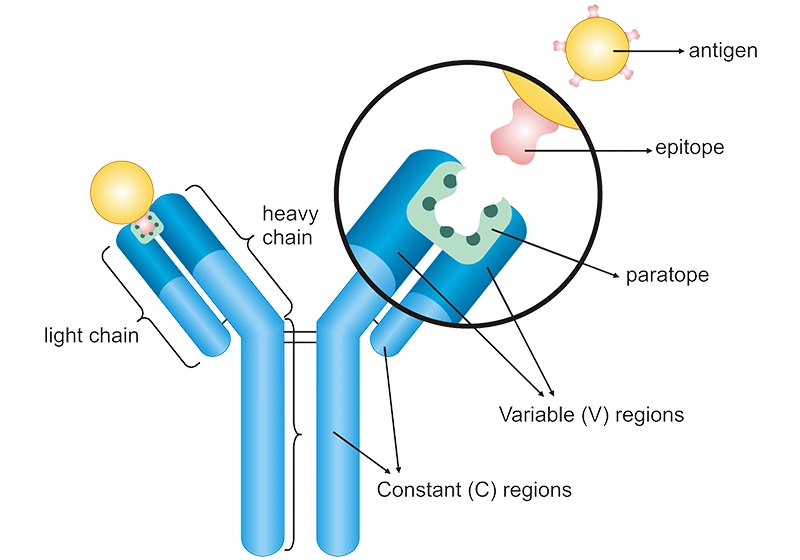

Specificity: It can be regarded as a measure of the goodness of fit between paratope and epitope, or represents the ability of the antibody to discriminate similar or even dissimilar antigens in the intended application. An antibody with low specificity binds to several different epitopes.

Figure 1: The specific binding between an antibody and an antigen

Affinity: It measures the intensity of the interaction between an antibody and an antigen (epitope). A high-affinity antibody firmly binds to a specific antigen, while a low-affinity antibody weakly binds to the antigen. The higher the affinity of an antibody, the higher the sensitivity of an antibody-based assay.

The equilibrium association constant (Ka) is the basic parameter to evaluate the binding affinity. The Ka is the ratio of antibodies association rate (Kon) to the antibody dissociation rate (Koff). Compared with a low-affinity antibody with a low Ka, a high-affinity antibody with a high Ka will bind more antigens in a shorter period.

Selectivity: It describes how well an antibody binds to its intended target antigen within a complex mixture. An antibody selectivity for a certain antigen means that it shows little cross-reactivity with other antigens.

Reproducibility: It means that the validation data can be reproduced in any lab. However, antibodies vary from batch to batch. The batch-to-batch variability can produce significantly differing results. Compared with polyclonal antibodies and monoclonal antibodies, recombinant antibodies exhibit great superiority in reproducibility.

Generally speaking, what we usually refer to as antibody validation actually refers in most cases to the validation of antibody specificity.

3.1 Methods to Validate Antibody Specificity

Validation of antibodies needs to meet the applicability of an antibody in a specific application. Frequently used methods include Western blot (WB) antibody validation, ELISA antibody validation, immunofluorescence (IF) antibody validation, immunohistochemistry (IHC) antibody validation, immunocytochemistry (ICC) antibody validation, immunoprecipitation (IP)-mass spectroscopy (MS) antibody validation, flow cytometry (FC) antibody validation, knockout cell line, and knockdown cell line. Here is the list of the comparison among different methods.

Table 1. Antibody validation methods

| Validation types |

Detection mechanism |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| WB |

Proteins in a sample are detected through initial molecular weight separation after SDS-PAGE and subsequently blotted on a membrane, finally visualized through a proper antibody (e.g. colorimetric, chemiluminescent, fluorescent, and radioactive detection) |

- Effectively confirm whether the antibody specifically binds to the target protein based on molecular weight

- Ideal for detection of native or denatured proteins

- Qualitative assay

|

- Time-consuming

- Difficulty finding better experimental conditions (e.g. methods and buffers)

- Only a small number of antibodies can be detected per experiment

|

| ELISA |

Proteins in a sample are detected via specific antibodies and secondary enzyme-conjugated antibody |

- Suitable for high-throughput experiments with large numbers of samples

- Confirm that the antibody can recognize the protein containing the antigenic peptide sequence

- Easy to optimize steps and buffers

- Quantitative or qualitative assay

|

- Unable to confirm whether the antibody recognizes or cross-recognizes the target protein

|

| IMS |

Protein complexes are first immunoprecipitated from a cell lysate and then separated via SDS-PAGE, followed by excision of protein bands of interest, and finally analyzed with mass spectrometry |

- Suitable for a high-throughput format

- Can confirm the specific interaction of the antibody with the intended target protein

- Can recognize all protein isoforms to which the antibody binds

- Can identify post-translational modifications, interacting partners, and complexes

|

- Not all antibodies are suitable for IP

- Difficult to discriminate partner proteins pulled down in a complex from off-target binding

- An antibody may not recognize a target protein in an undenatured state.

|

| IHC |

Proteins in tissue sections are detected via specific antibodies and the antigen-antibody reaction is visualized by color-labeled secondary antibody |

- Verify whether the antibody can recognize the target protein by localization in the cell

- Specificity depends on whether the cell expresses the target protein

- Qualitative assay

|

- Unable to determine whether the antibody recognizes other proteins with the same cellular localization

- It is often difficult to confirm whether a cell or tissue expresses the target protein

|

| ICC |

Proteins in single layers of cells grown in culture or from a patient sample are detected via specific antibodies and the antigen-antibody reaction is visualized by fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody |

- Verify whether the antibody can recognize the target protein by localization in the cell

- Specificity depends on whether the cell expresses the target protein

- Qualitative assay

|

- Unable to determine if an antibody recognizes other proteins non-specifically with identical cellular localization

- It is often difficult to confirm whether a cell or tissue expresses the target protein

|

| FC |

When the target antigen is recognized by the fluorescence-labeled special antibody, the fluorescence signal will be acquired by Flow cytometry |

- Validation of antibodies by cell type

- High-throughput experiments

- The experimental procedure is easy to optimize

|

- Unable to confirm whether the antibody non-specifically recognizes other proteins

- It is often difficult to confirm whether a cell type expresses the target protein

|

| IF |

The target protein is detected by a specific fluorescence-labeled antibody, and the fluorescence signal is observed under a fluorescence microscope |

- Strong specificity, high sensitivity, fast speed, easy to operate

- Qualitative assay

|

- The problems of non-specific staining make the objectivity of the result determination insufficient

- The technical procedure is relatively complicated

|

| Knockout (KO) cell line |

Cell lines where the protein-encoding gene of interest is deleted with genetic tools such as CRISPR |

- Ensure that the target gene is not expressed

- Ensure the specificity of the antibody

- Knockout cell lines can be used as proper negative controls

- Numerous potential knockout cell lines can be made in a short time

- Knockout cell lines can be used for all experiments - WB, IHC, ICC, FC, etc.

|

- Knockout cell lines for specific genes are often not available

- The absence of signal in KO samples demonstrates that the antibody recognizes the target protein in wild-type samples. But it does not guarantee that the antibody will not bind an unspecific ally to an unassociated protein in a different sample background.

|

| Knockdown (KD) cell line |

Protein-encoding gene expression is lowered using post-transcriptional gene regulation tools, such as siRNA |

- Confirm the specificity of the antibody by down-regulation of the target protein content

- Knockout cell lines can be used for all experiments - WB, IHC, ICC, FC, etc.

|

- Knockdown is transient

- Experiments are difficult to optimize

- When the siRNA attaches to similar transcripts and silences "off-targets," non-specific reduction in expression may be seen.

|

The International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) proposed five conceptual pillars for the validation of antibodies in specific applications [2][4].

(1) Genetic strategies

Genetic strategies employ gene knockout (KO) or gene knockdown (KD) technology to verify the specificity of antibodies. Scientists can use gene editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi to knock out or knock down the target gene and then use specific antibodies for detection. If the antibody's binding signal is not observed or significantly reduced in the knocked-out or down cell lines, it indicates that the antibody has good specificity.

Genetic strategies are suitable for antibody specificity validation through WB, IHC, ICC, FS (flow sorting and analysis of cells), ELISA, IP/ChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation), and RP (reverse-phase protein arrays). However, they can not used for human tissue samples and body fluids such as plasma and serum.

(2) Orthogonal strategies

Orthogonal strategies aim to validate antibody specificity by employing an antibody-independent technique for quantifying the target across multiple samples, followed by analyzing the correlation between this method and antibody-based target quantification. Multiple techniques such as immunoprecipitation (IP), mass spectrometry (MS), and WB can be combined to assess the specificity of the same antibody, providing a more comprehensive validation. Confidence in the specificity of an antibody can be enhanced if multiple methods yield consistent results.

Orthogonal strategies are recommended for antibody validation through WB, IHC, ICC, FS, ELISA, and RP.

(3) Independent antibody strategies

The independent antibody approach uses two or more independent antibodies (antibodies from different sources or lots) to recognize nonoverlapping epitopes on the same protein, and then confirm the specificity by comparison and quantitative analysis.

Independent antibody validation is recommended in the applications, including WB, IHC, ICC, FS, ELISA, IP/ChIP, and RP.

(4) Expression of tagged proteins

This strategy emphasizes the use of verified antibodies as controls to compare the performance of antibodies to be verified. Modify the endogenous target gene, that is, adding the affinity tag (FLAG, V5, etc.) or fluorescent protein (green fluorescent protein) to the endogenous gene, and then detect and compare the signal from the tagged protein using verified antibodies and antibodies to be tested.

This validation strategy can be used in WB, IHC, ICC, and FS applications for antibody specificity validation.

(5) IMS

IP can be used to isolate the target protein by using antibodies to bind specifically to the target protein. Its combination with MS analysis (IMS) can identify target proteins that interact directly with purified antibodies or proteins that may form complexes with target proteins. If the precipitation is successful and the target protein is subsequently detected, the effectiveness of the antibody can be proven. This strategy can be used in IP/CHIP applications.

3.2 Key Tips to Validate An Antibody

To ensure the effectiveness and reliability of antibodies, researchers should follow some key practices.

a. Choose correct negative control vs positive control

Positive controls are tissue sections or cell lines known to express the target protein. Non-expressing cells that have been transfected with the protein of interest offer the finest positive controls [2]. Positive controls provide a benchmark for experimental results, and researchers can evaluate the reaction strength and specificity of experimental samples by comparing with the results of positive controls.

Negative controls are cell or tissue samples that do not express the target protein. Negative controls can reveal whether there is nonspecific binding or false positive reactions of antibodies. The results of negative controls provide support for the validity of the experiment, ensuring that the observed signal is caused by the specific binding of the antibody to the target antigen and not caused by other factors.

Knockout cells or animals offer the most effective negative controls. VG Magupalli et al. validated anti-NLRP3 and anti-ASC antibodies with respective knockout cells [3]. There are alternative methods that can be utilized to produce comparable control results because these reagents are frequently out of the price range of many labs.

Frequently, it could find cell lines that have been biologically shown to not express a certain protein of interest. For instance, PTEN-null H1650 cells serve as an excellent negative control for PTEN antibodies. siRNA or shRNA knockdown controls are also used as negative controls. When a proper negative control is not available, a cell line or tissue expressing only a small amount of the target proteins can serve as an acceptable substitute.

Positive controls can help confirm the specificity of the antibody and the validity of the experimental setup, while negative controls help identify false positive results, thereby avoiding misinterpretation of experimental data. When performing experiments, proper positive and negative controls can help identify potential experimental errors and background signal interference, thus increasing the confidence of the results.

b. Optimization of experimental steps

Selecting the best experimental procedure is an important part of ensuring that the antibody passes the validation process. Use appropriate blocking agents and dilution buffers in your experiment to reduce nonspecific binding. You can optimize your experiment by adjusting conditions such as antibody concentration, incubation time, washing time, and storage and use conditions (e.g. buffer, temperature).

c. Multiple validations in different applications

Different antibodies may perform differently in specific experiments (WB, ELISA, IHC, FC, etc.) and need to be verified item by item. Use multiple methods to validate the performance of antibodies as much as possible, such as cross-validation through different experimental techniques to improve the credibility of the results.

d. Antibody batch validation

The characteristics of each batch of antibodies may be different, so each batch of antibodies should be independently validated. Confirm the stability of antibodies in different production batches to avoid inconsistent experimental results due to batch differences.

Of course, no matter what detection method is used, we need to know in advance the background investigation of the target, including the expression abundance of the target, the spatiotemporal specific expression of the target, the detection threshold of the target antibody, and the appropriate detection method. Only through the analysis of scientific background knowledge, the most suitable method can be selected and a scientific validation strategy can be formulated.

Finally, specific criteria and factors must be met in order to successfully validate and confirm the specificity of an antibody. The specificity of antibodies is dependent on background conditions. Antibodies can only be properly validated in the context of the applied technology and the conditions under which they are ultimately used.

Comments

Leave a Comment