SARS-COV-2, which is ravaging around the world, has been the research hotspot since its breakout in late 2019. At the

unremitting efforts of scientific researchers, several types of vaccines against SARS-COV-2 were successfully developed. The SARS-COV-2 evolves over time, with new variants emerging. A concern is

ensuing: are those authorized vaccines still effective against new variants? Experts note that current vaccines are still effective against new SARS-CoV-2 variants although the efficacy reduces. Why are existing vaccines still effective against new variants of SARS-CoV-2? The cross-reactivity of antibodies could explain this

phenomenon to some extent.

In this article, we will focus on the definition, causes, biological significance, applications, and prevention of cross-reactivity.

1. What Is Cross-reactivity?

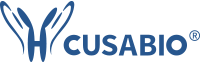

Epitope and paratope have to be mentioned before talking about the cross-reactivity.

1.1 Epitope and Paratope

An epitope is a specific sequence of amino acids (only 5-6 amino acids long) lying on the surface of an antigen and is recognized by the corresponding antibody. The epitope

is also called an antigenic determinant. Some antigens have only one epitope, while others have two or more different epitopes.

A paratope is a three-dimensional structure formed by the complementary binding of the tip part of variable regions (light and heavy chains) of the antibody. It contains 5-10 amino acids and

specifically recognizes and binds to the epitope of an antigen. Each arm of the Y-shaped antibody has an identical paratope at the N-terminal end. As such, antibody-antigen binding is actually the

paratope-epitope interaction.

Figure 1: The structure diagram of antibody-antigen binding

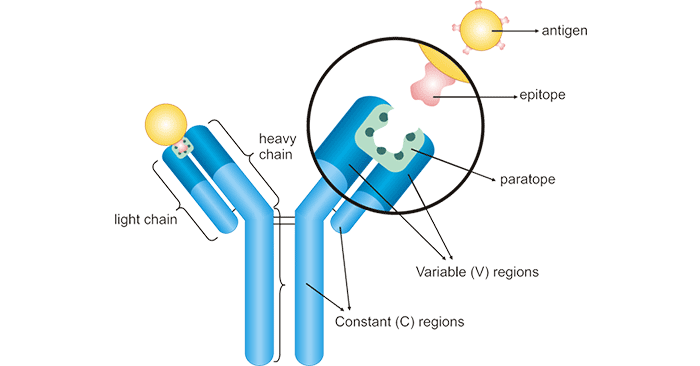

1.2 What Is Cross-reaction?

An antibody reacts with antigens other than the antigen that stimulated it. This phenomenon is called cross-reaction. Cross-reaction occurs due to the shared epitope on

multivalent antigens or conformational similarity of epitopes.

Figure 2: The cross-reaction of an antibody between two different antigens

1.3 Cross-reactivity

Cross-reactivity is commonly defined as the capacity of a single antibody to recognize the same or structurally similar epitopes on different antigens in immunology.

2. The Association and Difference between Cross-Reactivity and Specificity

In immunology, specificity refers to the ability of paratopes on an antibody to recognize and interact with only a single epitope on the corresponding antigen. It should be

noted that this unique epitope may be present on more than one antigen. The specificity is determined by the types, arrangement order, and spatial configuration of epitope(s) on the antigen. The specificity

enables to precisely detect a target antigen thus avoiding measurement of impostor antigens. It is the most prominent feature of immune response and is the basic basis for the prevention and diagnosis in

immunology.

Cross-reactivity refers to a situation in which an antibody recognizes and binds to two or more antigens that are highly homologous or possess the same epitope. In immunoassays, cross-reactivity of

antibody (polyclonal antibody) enhances the sensitivity of the result and allows for the detection of antigens with low abundance.

Specificity evaluates the extent to which the immune system distinguishes between different antigens. While cross-reactivity assesses the degree to which different antigens resemble the immune

system. To some extent, cross-reactivity greatly reduces specificity.

3. The Biological Significance of Cross-reactivity

Cross-reactivity of antibodies shows both defensive and offensive properties. The cross-reactive antibody provides cross-protective immunity to related pathogen strains or

antigenic variants in natural epidemiology. In other words, the defensive action of antibody cross-reactivity imparts a broader immunity against pathogens or provides cross-protective immunity to related

pathogens. Evidence has been shown that the antibody cross-reactivity is a mechanism to escape the immune response for numerous human pathogens, including schistosomiasis [1], influenza

virus [2], and Streptococcus pneumoniae [3]. However, antibody cross-reactivity may be detrimental for the hosts. Offensive roles of antibody cross-reactivity are mainly reflected in

the induction or exacerbation of infective diseases, autoimmune diseases, and allergy as a consequence of inappropriate or deleterious inflammatory responses related to host tissue destruction [4] . In serological diagnosis, cross-reactivity of antibodies will cause confusion in specific diagnosis or identification.

Besides, cross-reactivity can interfere with the results of immunoassays and affect reproducibility. A cross-reaction may lead to a false positive interference in drugs of abuse screening tests because

the antibody reacts to another compound possessing a chemical structure similar to the targeted drug [5] [6].

4. Applications of Cross-reactivity

Cross-reactivity can improve the utility of an antibody. For example, the cross-reactivity of an antibody enables it to detect the homologous proteins in multiple model

organisms. Many human antigen-derived antibodies show significant cross-reactivity with the homologous proteins in non-human organisms, such as mouse, rat, and rabbit. The cross-reaction across

different species can be used to explain certain immunopathological phenomena, diagnose certain infectious diseases, or induce immune responses against antigens that are difficult to prepare. Cross

reaction can confirm that whether the ELISA kit is specific for detecting a certain protein of interest.

In clinical diagnosis, heterophile antibody tests are used to rapidly detect antibodies generated against the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis [7].

These tests make use of the cross-reactivity of antibodies. Cross-reactivity has been frequently used as an evaluated parameter for the validation of immune and protein binding-based assays such as ELISA

and RIA.

5. How Can Cross-reactivity Be Avoided or Decreased?

Testing the cross-reactivity of antibodies with closely related antigens is an important validation test. Choosing appropriate antibodies is the most direct solution to avoid

cross-reactivity in immunoassays. It is recommended that mAb is used as a primary antibody (e.g. for capture) to establish high assay specificity, and that pAb should be used as a detection antibody for

higher sensitivity.

To avoid cross-allergic reactions, a patient must not take drugs with similar chemical structures to the certain drug known to induce allergic reactions. Erythromycin, medemycin, chiamycin,

spiramycin, and other large ring lactone drugs have cross-allergy.

Since antibodies are being developed to treat a wide range of diseases including cancer, a fuller understanding of cross-reactivity is particularly important.

References

[1] Fitzsimmons CM, Jones FM, et al. Progressive cross-reactivity in IgE responses: an explanation for the slow development of human immunity to schistosomiasis [J]? Infect. Immun. 2012,

80:4264–4270.

[2] Nara PL, Tobin GJ, et al. How can vaccines against influenza and other viral diseases be made more effective [J]? PLoS Biol. 2010, 8:e1000571.

[3] Väkeväinen M, Eklund C, et al. Cross-reactivity of antibodies to type 6B and 6A polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae evoked by pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, in infants [J]. J.

Infect. Dis. 2001, 184:789–793.

[4] Daria Augustyniak, Grazyna Majkowska-Skrobek, et al. Defensive and Offensive Cross-Reactive Antibodies Elicited by Pathogens: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly [J]. Curr Med Chem. 2017

Nov 24;24(36):4002-4037.

[5] Gagajewski A, Davis GK, et al. False-positive lysergic acid diethylamide immunoassay screen associated with fentanyl medication [J]. Clin Chem. 2002;48:205–6.

[6] Lichtenwalner MR, Mencken T, et al. False-positive immunochemical screen for methadone attributable to metabolites of verapamil [J]. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1039–41.

[7] Tess Marshall-Andon and Peter Heinz. How to use …the Monospot and other heterophile antibody tests [J]. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017 Aug;102(4):188-193.

CUSABIO team. Cross-reactivity of Antibody: Beneficial or Harmful?. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21045.html

Comments

Leave a Comment