As a member of the glycoprotein subfamily of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily, FSHR participates in signal transduction by binding to ligands. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) is a glycoprotein hormone secreted by the pituitary gland. FSH can stimulate the development of follicles in female ovaries and promote spermatogenesis in male testes by binding to FSHR.

1. Molecular Structure of FSHR

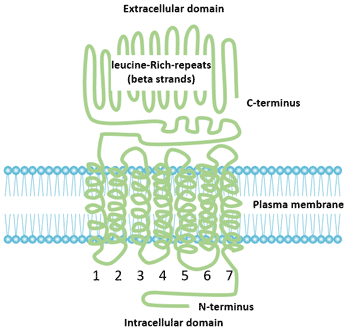

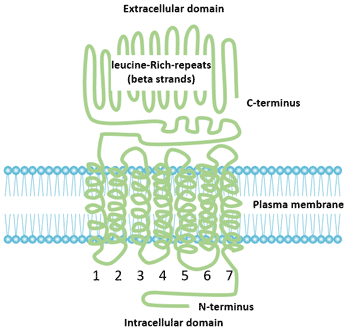

FSHR belongs to the glycoprotein subfamily of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily [1], which consists of 678 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of approximately 76.5 kD. FSHR is a membrane receptor composed of four oligosaccharide protein monomers linked by disulfide bonds. The interaction between FSH and FSHR depends not only on membrane phospholipids, but also on the combination of disulfide bonds. FSHR can be divided into three parts: extracellular domain, intracellular domain and transmembrane domain.

Figure 1 Structure of follicle-stimulating hormone and entire ectodomain of FSHR

1.1 Ectodomain

Each repeat is a structural unit composed of alternating β-sheets and α-helices formed by approximately 24 amino acids. The extracellular domain is rich in leucine-repeats (LRR) motifs that are involved in cell-specific adhesion and protein interactions. The extracellular domain has a glycosylation site, which is necessary for the folding of the receptor and transport of the hormone to the surface of the membrane. The extracellular domain contains several cysteine (Cys) residues that are important for the conformational integrity of the extracellular domain of all glycoprotein hormone receptors. The extracellular domain has FSH specific binding sites, which vary in size according to the ligand binding type.

1.2 Transmembrane Domain

The FSHR transmembrane domain is a transmembrane protein complex composed of 7 lipophilic helices inserted into the cell membrane. The main function of the transmembrane domain is to participate in signal transduction mediated by protein kinase A (PKA) and initiate intracellular events after receptor activation. The intramolecular disulfide bond stabilizes the protein conformation. The highly conserved aspartic-arginine-tyrosine (Asp-Arg-Tyr) triad motifs play an important role in hormone-receptor interactions.

Figure 2 Structure of FSHR

2. FSHR Gene

In 1989, the inferred FSHR DNA fragment sequence was first reported. In 1990, the cDNA of follicle stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) was cloned for the first time. The human FSHR gene is located in the short arm 2 region of chromosome 2 and is a single copy gene of 54 kb in length. Sheep and pigs are located on chromosome 3. The human FSHR gene contains 10 exons and 9 introns and a promoter region [2]. The extracellular domain is encoded by nine exons; the C-terminus, transmembrane domain, and intracellular domain of the extracellular domain are all encoded by exon 10.

3. The Tissue Distribution of FSHR

The expression of FSHR is considered as gonadal-specific. For A long time, it has been believed that the expression of FSHR is limited to the granulosa cells of the ovary and the supporting cells of the testis, but it was subsequently found that FSHR is expressed in placenta, uterus, prostate, bone tissue and ovarian epithelium as well as ovarian cancer [3] [4].

Interestingly, FSHR has recently been found to be selectively expressed on the surface of many tumor blood vessels, and it has been found that FSHR expression is closely related to tumor metastasis in primary renal cell carcinoma. The expression levels of FSHR are also different at different stages of female follicular development.

4. Signal Transduction Mechanism of FSHR

The signaling process of the FSHR consists of four steps:

-

The ligand specifically binds to the receptor. The binding site for hormones is in the extracellular domain of the receptor [5]. Transmembrane domains may facilitate high affinity binding.

-

Signal transduction. The binding of FSH to the receptor increases the cAMP of granulosa cells or Sertoli cells, activates protein kinase A (PKA), and leads to activation of some proteases and transcription factors.

-

Receptor desensitization. Agonist-induced receptor desensitization leads to a decrease in receptor function (uncoupling) and a down-regulation of the number of receptors. This uncoupling can be achieved by phosphorylation of the C-terminus of the intracellular domain of the receptor, receptor-specific kinase or the action of the receptor system PKA or PKC.

-

Events after receptor activation.

Obstacles in any of the above steps will affect the physiological role of hormones.

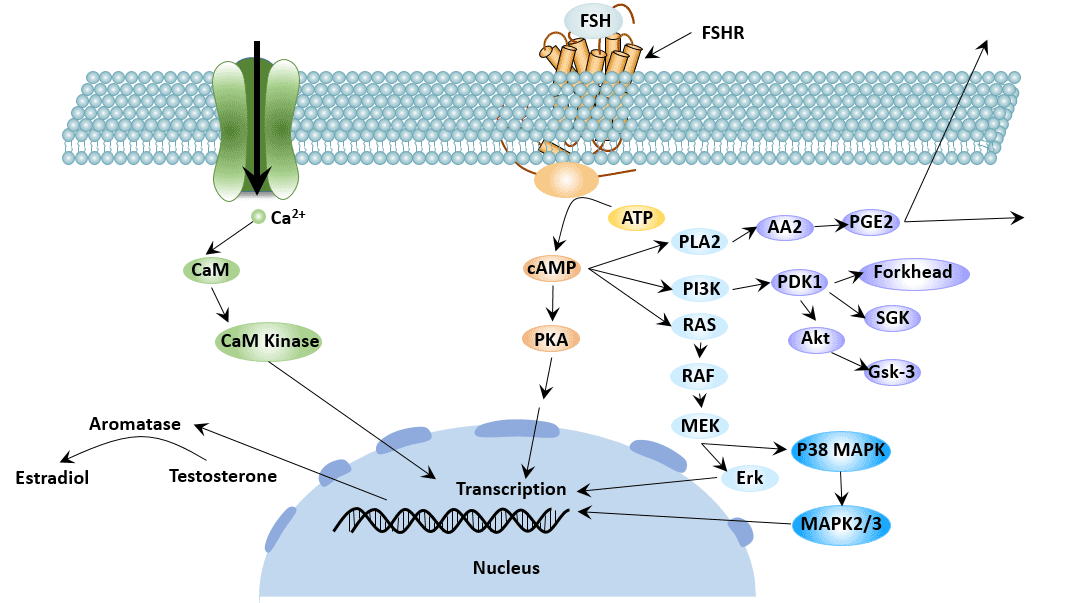

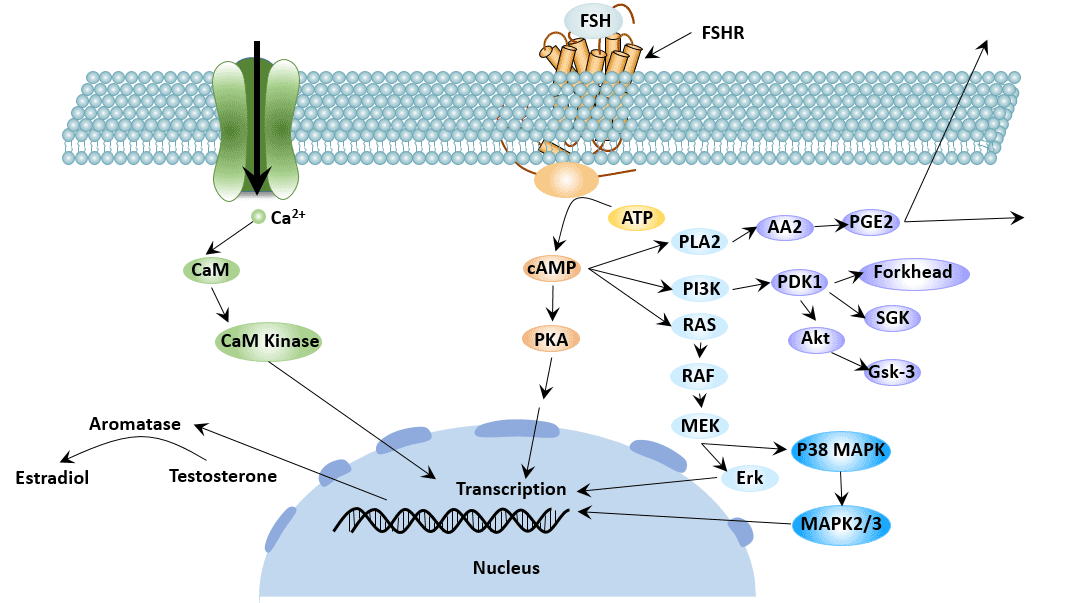

The cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-protein kinase A (PKA) pathway is the main signal transduction pathway that FSHR participates in. In addition, FSHR is also involved in some other signal transduction pathways, such as extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling pathway and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) signaling pathway, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) pathway and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-serine/threonine Acid kinase pathway and activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway [6].

Figure 3 FSHR-mediated signaling pathways

5. FSHR Polymorphism

FSHR gene mutation is the molecular pathological basis of gonadal dysfunction.

5.1 FSHR Mutation

Since the first discovery of FSHR point mutations in 1995, a total of 13 mutations have been identified, which are classified into functionally inactivated mutations and functionally activated mutations. There are 9 inactivating mutations and 4 functional activating mutations in FSHR. The inactivating point mutation of the first FSHR gene, Alal89Val, has a profound effect on the reproductive phenotype [7]. The effect on men is affecting the quality of sperm, but can produce offspring normally. The effect on women is manifested as hypergonadotrophic amenorrhea.

* SNP of Exon 10 of FSHR

Single nucleotide polymorphisms at 307 and 680 of exon 10 are the most common in FSHR [8]. It is manifested as 307 site threonine (Thr) can be substituted by alanine (Ala) or 680 site serine (Ser) can be substituted by aspartic acid (Asn). Thr307Ala is located in the FSHR extracellular hinge region, connecting the hormone binding domain with the transmembrane domain. The mutation can affect hormone transport and signal transduction.Asn680Ser is located in the intracellular domain, which can affect the decoupling of adenylate cyclase [9].

* Single Nucleotide Polymorphism of the FSHR Promoter

The polymorphism of the promoter sequence has an important effect on the affinity of the promoter with the enzyme and the expression level of the final FSHR, but has no significant effect on the serum FSH level.

In addition, during the expression of the FSHR gene, the apparent structure of the DNA sequence (eg, degree of methylation) can also have an important effect on the expression level of FSHR. For example, methylation at specific sites may strongly inhibit the expression of FSHR, while demethylation leads to increased levels of FSHR expression [10].

Sequence polymorphisms and epigenetic polymorphisms of FSHR promoters may affect the sensitivity of cells to FSH by regulating the transcriptional activity of FSHR.

In addition to gene mutation, gene isomers also play an important role in FSHR function.

5.2 FSHR Isomer

Four different FSHR isomers exist due to different splicing mechanisms of FSHR exons.

* FSHR1

The FSHR1 variant is the full-length form of FSHR. It is a typical phenotype of G protein coupled receptors. The structure of FSHR1 typically includes a large extracellular N-terminal domain that binds to FSH and an intracellular C-terminal domain segment, 7 α-helical membranes are alternately connected by extracellular and intracellular circulation. FSHR1 is expressed only in ovarian granulosa cells and its primary function is to participate in follicular development and granulosa cell differentiation [11].

* FSHR2

Unlike FSHR1, FSHR2 retains the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the receptor, but not the intracellular domain. This variation retains the high affinity binding of FSHR to FSH, but lacks the ability to activate G protein when bound to FSH [2].

* FSHR3

FSHR3 subtype has a single transmembrane domain, and the overall topology of FSHR3 is consistent with that of the growth factor I receptor. FSHR3 promotes growth by activating MAPK and Ca2+-dependent channels [12]. FSHR3 may play an important role in promoting mitotic activity and cell growth.

* FSHR4

FSHR4 lacks any transmembrane domain and is called soluble FSHR. FSHR4 stabilizes or blocks the binding of hormones to FSHR by binding to FSH in the extracellular matrix. FSHR4 may function like the insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 binding protein [13]. But its exact function is unclear.

6. FSHR Function

6.1 FSHR Gene Mutation and Male Fertility

FSHR is a FSH receptor specifically expressed on the surface of testicular Sertoli cells and plays an important role in the development of adult male sperm. In males, FSH binds to the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) on the Sertoli cell membrane, activates the signal pathways such as cAMP-PKA, MAPK, calcium channel, and PI3K/PKB, and converts the signal from FSH into various factor signals required by spermatogenic cells, supporting the spermatogenesis process [14].

FSHR genotype was correlated with reproductive parameters such as testicular volume. Multiple SNPs combinations of FSHR genes can significantly affect male infertility [15] [16].

According to the role of follicular estrogen receptor (FSHR) in male spermatogenesis, the vaccine of follicular estrogen receptor (FSHR) can be developed to indirectly block the iological function of FSH and inhibit the generation of spermatozoa, thereby achieving the purpose of contraception.

6.2 Effect of FSHR Gene Mutation on Female Reproductive Function

Ovarian function begins to decline after a woman reaches her baby peak at age 25. With the increase of age, the aging speed of ovary is also accelerated [17] [18]. Of course, there are limitations in evaluating ovarian reserve function solely by age. In addition to age, the patient's ovarian reactivity should also be considered.

In females, FSHR gene mutation can cause the regulation disorder of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, which directly affects the growth and ovulation of follicles.

* Effect of FSHR Gene Mutation on Ovarian Function

The effect of FSHR gene mutation on fertility function is mainly reflected in the effect on ovarian function. The main clinical manifestations of patients with FSHR gene mutation are follicular maturation disorder and endocrine dysfunction.

The FSHR gene may also be associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in the female reproductive system, with high mortality, high recurrence rate, and high metastasis rate. FSHR may be associated with the development of ovarian cancer in two ways: structural polymorphism of the receptor itself; differential expression in normal tissues and cancerous tissues.

* Effect of FSHR Gene Mutation on Uterus

FSHR mRNA is expressed in the endometrium and its expression is significantly different at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Studies have shown that FSHR may be involved in the regulation of endometrial function and may be involved in the process of embryo implantation.

7. Relationship between FSHR and Tumor

Loss or overexpression of FSHR may affect normal signal transduction, thereby promoting tumorigenesis.

In addition to its role in reproductive system tumors such as ovarian cancer and prostate cancer, the role of FSHR in other tumors has also been reported in recent years. Expression of FSHR is found in various tumor tissues such as human breast, colon, pancreas, bladder, kidney, lung, liver, stomach, testis and ovary [19].

7.1 Malignant Tumor of Urinary System

FSHR was positive in prostate, bladder and kidney cancer. FSHR may play an irreplaceable role in the occurrence, development and metastasis of prostate cancer, and is an ideal target vector for prostate cancer.

7.2 Malignant Tumor of Reproductive System

FSHR can stimulate the proliferation of ovarian tumor cells, improve the ability of tumor invasion, and promote tumor growth [20]. The expression level of FSHR was positively correlated with the differentiation degree of ovarian tumors [21].

7.3 Malignant Tumor of Digestive System

FSHR expression can be seen on vascular endothelial cells of colon cancer and gastric cancer. This is consistent with the idea that invasive tumor cells infiltrate the surrounding blood vessels and develop into tumors.

FSHR is widely expressed in tumor vascular endothelial cells and may play an important role in tumor angiogenesis. FSHR can effectively distinguish tumor tissue from normal tissue, indicating its potential therapeutic value as a tumor imaging agent and targeting tumor neovascularization. Therefore, the development of inhibitors against FSHR targets can block tumor angiogenesis independent of VEGF and exert anti-tumor effects.

8. Targeted Drug for Follicle Stimulating Hormone Receptor

FSHR is highly expressed in the endothelium of many other tumors and plays an important role in the progression of the disease. Therefore, FSHR is a potential target for tumor diagnosis and treatment. Currently, the main targeted drugs are as follows:

Compounds targeting FSHR: FSH is a gonadotropin secreted by the pituitary gland and a glycoprotein composed of two peptide chains, α and β. The β peptide chain is responsible for binding to FSHR, producing a range of biological functions [22]. FSHβ33-53, FSHβ81-95 and FSHβ85-95 can be combined with FSHR and can be used as a targeting vector for tumors for diagnosis and treatment [23].

A polypeptide probe targeting FSHR: Currently, polypeptide probes targeting prostate cancer have been prepared [24]. Current studies have shown that polypeptide probes targeting FSHR are a feasible research, and their application value in the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of prostate cancer or other tumors can be further discussed in the future.

References

[1] O'Shaughnessy P J, Dudleyb K, Rajapaksha W R. Expression of follicle stimulating hormone-receptor mRNA during gonadal development [J]. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 1996, 125(1-2): 169-175.

[2] Themmen A P N, Huhtaniemi I T. Mutations of Gonadotropins and Gonadotropin Receptors: Elucidating the Physiology and Pathophysiology of Pituitary-Gonadal Function [J]. Endocrine Reviews, 2000, 21(5): 551-583.

[3] Marca A L, Artenisio A C, Stabile G, et al. Evidence for cycle-dependent expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in human endometrium [J]. Gynecological Endocrinology, 2006, 21(6): 303-306.

[4] Patsoula E, Loutradis D P, Michalas L, et al. Messenger RNA expression for the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor and luteinizing hormone receptor in human oocytes and preimplantation-stage embryos [J]. Fertility & Sterility, 2003, 79(5): 1187-1193.

[5] Braun T, Schofield P R, Sprengel R. Amino-terminal leucine-rich repeats in gonadotropin receptors determine hormone selectivity [J]. The EMBO Journal, 1991, 10(7): 1885-1890.

[6] Mertens-Walker I, Baxter R C, Marsh D J. Gonadotropin signalling in epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. Cancer Letters, 2012, 324(2): 152-159.

[7] AittomaKi K, JoséLuis Dieguez Lucena, Pakarinen P, et al. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure [J]. Cell, 1995, 82(6): 0-968.

[8] JeoRg G, Manuela S. Genetic complexity of FSH receptor function [J]. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism Tem, 2005, 16(8): 368-373.

[9] Yang C, Chan K, Ngan H, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor are associated with ovarian cancer susceptibility [J]. arcinogenesis, 2006, 27(7): 1502-6.

[10] Griswold M D. Site-Specific Methylation of the Promoter Alters Deoxyribonucleic Acid-Protein Interactions and Prevents Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Gene Transcription [J]. Biology of Reproduction, 2001, 64(2): 602-610.

[11] Ulloa-Aguirre A, Teresa Zarinan, Pasapera A M, et al. Multiple facets of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor function [J]. Endocrine, 2007, 32(3): 251-263.

[12] Touyz R M, Jiang L G, Sairam M R. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Mediated Calcium Signaling by the Alternatively Spliced Growth Factor Type I Receptor [J]. Biology of Reproduction, 2000, 62(4): 1067-1074.

[13] Mayorga M P, Gromoll J, Behre H M, et al. Ovarian Response to Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) Stimulation Depends on the FSH Receptor Genotype [J]. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2000, 85(9): 3365-3369.

[14] Ichihara I, Pelliniemi L J. Morphometric and ultrastructural analysis of stage-specific effects of Sertoli and spermatogenic cells seen after short-term testosterone treatment in young adult rat testes [J]. Annals of Anatomy, 2007, 189(5): 520-532.

[15] Lindgren I, Giwercman A, Axelsson J, et al. Association between follicle-stimulating hormone receptor polymorphisms and reproductive parameters in young men from the general population [J]. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics, 2012, 22(9): 667-672.

[16] Ahda Y. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Gene Haplotype Distribution in Normozoospermic and Azoospermic Men [J]. Journal of Andrology, 2005, 26(4): 494-499.

[17] Alviggi C, Humaidan P, Howles C M, et al. Biological versus chronological ovarian age: implications for assisted reproductive technology [J]. Reproductive Biology & Endocrinology Rb & E, 2009, 7(1): 101-101.

[18] Chuang C C, Chen C D, Chao K H, et al. Age is a better predictor of pregnancy potential than basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels in women undergoing in vitro fertilization [J]. Fertility and Sterility, 2003, 79(1): 63-68.

[19] Radu A, Pichon C, Camparo P, et al. Expression of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor in Tumor Blood Vessels [J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010, 363(17): 1621-1630.

[20] Bose C K. Follicle stimulating hormone receptor in ovarian surface epithelium and epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. Oncology Research, 2008, 17(5): 231.

[21] Wang J, Lin L, Parkash V, et al. Quantitative analysis of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in ovarian epithelial tumors: A novel approach to explain the field effect of ovarian cancer development in secondary mullerian systems [J]. International Journal of Cancer, 2003, 103(3): 328-334.

[22] Desai S S, Roy B S, Mahale S D. Mutations and polymorphisms in FSH receptor: functional implications in human reproduction [J]. Reproduction, 2013, 146(6): R235-R248.

[23] Grasso P, Crabb J W, Reichert L E. An Explanation for the Disparate Effects of Synthetic Peptides Corresponding to Human Follicle-Stimulating Hormone β-Subunit Receptor Binding Regions (33-53) and (81-95) and Their Serine Analogs on Steroidogenesis in Cultured Rat Sertoli Cells [J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1993, 190(1): 0-62.

[24] Xu Y, Pan D, Zhu C, et al. Pilot Study of a Novel F-18-labeled FSHR Probe for Tumor Imaging [J]. Molecular imaging and biology: MIB: the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging, 2014, 16(4).

CUSABIO team. Effects of FSHR on Fertility and Tumors. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20874.html

Comments

Leave a Comment