Accumulating studies have reported that among the people who face the greatest harm from COVID-19 (the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2) are people with cancer [1]. And among those who have cancer, blood cancers like multiple myeloma may pose the most risk for both catching COVID-19 and getting seriously ill [2].

Actually, multiple myeloma is a relatively uncommon cancer. In the United States, the lifetime risk of getting multiple myeloma is 1 in 132, and the annual incidence of myeloma is 4.3 per 100 000. In 2020, the American Cancer Society's estimates that there are about 32,270 new cases of multiple myeloma will be diagnosed (17,530 in men and 14,740 in women), and about 12,830 deaths caused by multiple myeloma (7,190 in men and 5,640 in women). So what is multiple myeloma? In this article, we focus on the mechanism and treatment of multiple myeloma.

1. What is Multiple Myeloma?

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma-cell disorder that accounts for approximately 1% of neoplastic diseases and 10% of all hematologic cancers [3] [4]. MM is characterized by clonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow microenvironment, monoclonal protein in the blood or urine, and associated organ dysfunction [4]. It usually evolves from an asymptomatic premalignant stage of clonal plasma cell proliferation, referred to as “monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance” (MGUS). MGUS is present in more than 3% of the population above the age of 50 and progresses to myeloma or related malignancy at a rate of 1% per year [5] [6].

2. How does Multiple Myeloma Develop?

In multiple myeloma, plasma cells become cancerous and begin dividing rapidly. As a result, the malignant cells soon crowd out the healthy cells. These cancer cells can spread from marrow and invade the hard outer part of the bone. There, the cells clump to form tumors. When many tumors develop, this type of cancer is called multiple myeloma.

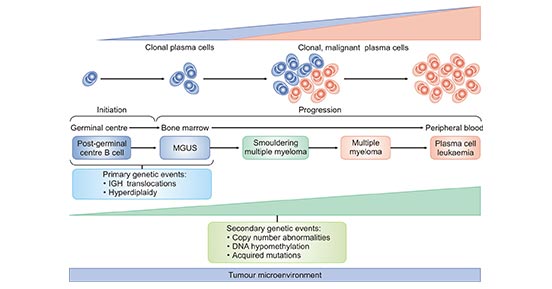

Multiple myeloma arises from an asymptomatic premalignant proliferation of monoclonal plasma cells that are derived from post–germinal-center B cells. The development of multiple myeloma is a multistep process. It usually starts with precursor disease states, such as MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). Although MGUS, SMM and multiple myeloma are clinically well defined, many biological similarities between these disease states have been found. Multiple myeloma can progress to bone marrow-independent diseases, such as extramedullary myeloma and plasma cell leukaemia. Primary genetic events in the development of MGUS, SMM and multiple myeloma include chromosomal translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy-chain genes (IGH) and aneuploidy (with hyperdiploidy as the most frequent entity). The number of secondary genetic alterations increases from MGUS to SMM and then to multiple myeloma.

Figure 1. The Development of Multiple Myeloma

*this diagram is derived from publication on Nature Reviews [7].

3. What are the Signaling Pathways Affected in Multiple Myeloma?

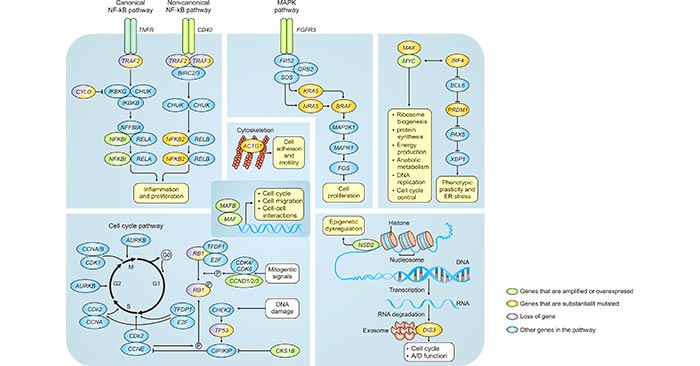

Multistep genetic changes in multiple myeloma can affect several cellular signaling pathways. As mentioned before, frequent genetic aberrations in patients with multiple myeloma include MYC rearrangements, mutations in KRAS and NRAS, translocation t. Several chromosomal translocations indicate a central role of the cyclin D proteins in multiple myeloma; t leads to overexpression of CCND1 and t leads to overexpression of CCND3 [8] [9]. CCND2 overexpression is also frequently observed in multiple myeloma. Other recurrent mutations include DIS3, TP53, BRAF, TRAF3, PRDM1, CYLD, RB1, MAX and ACTG1, of which (putative) functional links are indicated. These mutations can affect several cellular signaling pathways (as depicted in the figure 2).

Figure 2. The Signaling Pathways Affected in Multiple Myeloma

*this diagram is derived from publication on Nature Reviews [7].

NF‑κB signaling pathway is a critical pathway in B cells, and this pathway is deregulated in most B cell malignancies. Comparing with some other types of B cell malignancies, multiple myeloma is mostly characterized by the activation of the non-canonical NF‑κB pathway; alterations that affect the activation of this pathway include overexpression of CD40, mutations and deletions of TRAF2 or TRAF3 and mutations in NFKB2 (also known as P100), although aberrations that affect the canonical pathway have also been described, such as CYLD mutations. Signaling in the canonical pathways occurs through several receptors, including B cell receptor, Toll-like receptors and tumour necrosis factor receptor (TNFR).

Furthermore, for the non-canonical pathway, multiple receptors are involved including CD40 (also known as TNFRSF5), lymphotoxin-β receptor (also known as TNFRSF3) and also TNFR. Several genetic alterations indicate an important role for cell cycle deregulation in multiple myeloma, including overexpression of CKS1B, deletion and/or mutation of TP53 and frequent deletion of RB1. Other pathways of interest are the interaction with multiple myeloma cells and the microenvironment through overexpression of MAF oncogenes.

4. What are the Risk Factors of Multiple Myeloma?

A risk factor for multiple myeloma is anything that changes a person's chance of getting multiple myeloma. Having one or more risk factor doesn't mean that a person will get it. Here, we collect a few risk factors that could affect someone's chance of getting multiple myeloma.

-

Age. The risk of developing multiple myeloma goes up as people get older. The median age at diagnosis is approximately 70 years; 37% of patients are younger than 65 years (Less than 1% of cases are younger than 35), 26% are between the ages of 65 and 74 years, and 37% are 75 years of age or older [10] [11].

-

Gender. Men are slightly more likely to develop multiple myeloma than women.

-

Race. Multiple myeloma is twice as common in blacks compared with whites [11]. The reason is not known.

-

Family history. Multiple myeloma seems to run in some families. Someone who has a sibling or parent with myeloma is more likely to get it than someone who does not have this family history.

-

Obesity. Being overweight or obese increases a person’s risk of developing myeloma.

-

Having other plasma cell diseases. People with MGUS or solitary plasmacytoma are at higher risk of developing multiple myeloma than someone who does not have these diseases.

References

[1] Aakash Desai, Sonali Sachdeva, Tarang Parekh, et al. COVID-19 and Cancer: Lessons from a Pooled Meta-Analysis [J]. JCO Global Oncology. 2020, 557-559.

[2] First case of COVID-19 in a patientwith multiple myeloma successfully treated with tocilizumab [J]. Blood Adv. 2020, 4(7): 1307–1310.

[3] Antonio Palumbo, and Kenneth Anderson. Multiple Myeloma [J]. N Engl J Med. 2011, 364: 1046-60.

[4] Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma [J]. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351: 1860-1873.

[5] Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance [J]. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354: 1362-1369.

[6] Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma [J]. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 2582-2590.

[7] Shaji K. Kumar, Vincent Rajkumar, Robert A. Kyle, et al. Multiple myeloma [J]. NATURE REVIEWS. 2017, 17046.

[8] Turesson, I., Velez, R., Kristinsson, S. Y. et al. Patterns of multiple myeloma during the past 5 decades: stable incidence rates for all age groups in the population but rapidly changing age distribution in the clinic [J]. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 225–230.

[9] Huang, S. Y. et al. Epidemiology of multiple myeloma in Taiwan: increasing incidence for the past 25 years and higher prevalence of extramedullary myeloma in patients younger than 55 years [J]. Cancer. 2007, 110, 896–905.

[10] Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2007. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

[11] Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Dickman PW, et al. Patterns of survival in multiple myeloma: a population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003 [J]. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25:1993-9.

[12] Robert A. Kyle and S. Vincent Rajkumar. Multiple myeloma [J]. Blood. 2008, 111:2962-2972.

CUSABIO team. Multiple Myeloma, One of High-Risk Factors for COVID-19. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21008.html

Comments

Leave a Comment