In 1964, Hawkes et al. demonstrated enhanced infectivity of viruses, including arboviruses, Murray Valley encephalitis virus, West Nile virus (WNV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), and Getah viruses in the presence of virus-specific anti-sera (specifically IgG antibodies) at sub-neutralizing

concentrations [1]. This was the first description of "antibody-dependent infection enhancement" (ADE). ADE was first described in dengue virus (DENV) infection by Scott Halstead in 1973 [2] [3]. Other viruses have since been found to also exhibit ADE, including influenza A virus,

Coxsackievirus B, respiratory syncytial virus, Ebola virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

In this article, we will introduce the definition of ADE, mechanisms of the ADE, the significance of ADE research, whether ADE occurs in SARS-coV-2 infection, and solutions for reducing the risks of ADE.

1. What Is Antibody-dependent Enhancement?

Viral infections all initiate by adhering to the cell surface. Adhesion is accomplished by the interaction between virus surface

proteins and specific receptors on target cells. The virus-specific antibody can often block this step or "neutralize" the virus, making the virus lose the ability to infect cells [4]. However, in some

cases, instead of preventing the virus from invading human cells during the virus infection process, antibodies assist the virus to enter the target cell, enhance the replication of the virus in the body, and

increase the infection rate, causing severe pathological reactions. This phenomenon is known as the antibody-dependent enhancement effect (ADE) of virus infection.

Viruses occurring ADE most show a preference for multiplying in macrophages and are prone to cause persistent infection of the host. Conventional

vaccines are often difficult to prevent and treat such viral diseases [5], in some cases has been shown to increase the risk of infection of vaccine recipients.

2. Mechanisms of Antibody-dependent Enhancement

There are two mechanisms of ADE, both of which occur when non-neutralizing antibodies or sub-neutralizing concentrations of antibodies combine with viral

antigens without preventing or clearing the infection. Antibody-virus complexes attach to cells via the interactions between the Fc portion of IgG antibodies and Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) or complement

receptors and increase virus internalization, resulting in enhanced viral replication and aggravated disease severity. One is FcγR-mediated ADE (FcγR-ADE), which involves viruses, antibodies, and cell

surface FcγR; the other is complement-mediated ADE (C-ADE), which is related to viruses, antibodies, complement, and complement receptors.

2.1 FcγR-mediated ADE

In 1977, Scott Halstead et al. found that some people infected with one serotype of DENV may develop severe disease upon

secondary infection with a heterologous DENV serotype and linked the clinical severity of dengue to ADE [6] [7]. This was the first report of fragment crystallizable receptor (FcR)-mediated ADE.

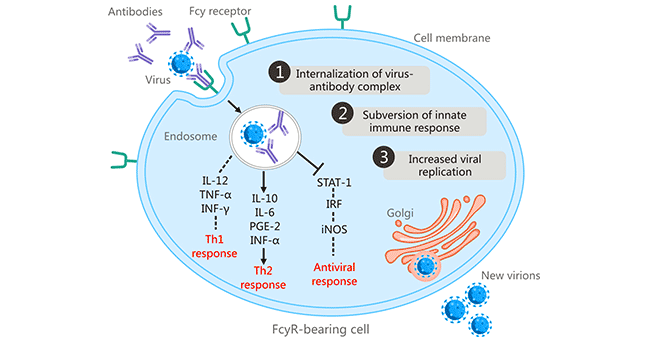

FcR-dependent ADE is considered to be the most common mechanism of ADE. ADE initiates when antibody-bound virus combines with FcγR-bearing cells (including macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells,

neutrophils Leukocytes, and granulocytes) via the Fc-FcγR interaction, promoting the internalization of the antibody-opsonized virus into cells through FcγR-mediated endocytosis or phagocytosis [8] . FcR-mediated ADE has been found in many viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Aleutian mink disease virus, respiratory syncytial virus, West Nile virus, and influenza A virus.

Figure 1: FcR-mediated antibody-dependent enhancement

The picture is cited from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6290032/

2.2 Complement-mediated ADE

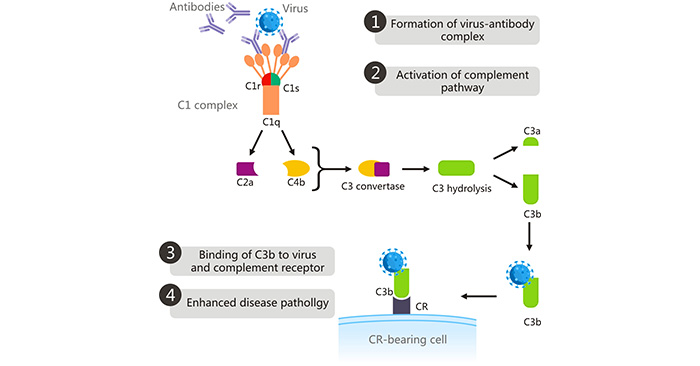

In the complement-mediated ADE, the complement opsonin C1q binds to the Fc domain of antibodies bound to the virus [9], which changes the conformation of the C1s C1r complex, activating the C1s C1r complex. Activated C1s cleaves complement C2 and C4, the resulting cleavage product of which form the C3

convertase (C4bC2a). The C3 convertase cleaves C3 into C3a and C3b. The highly reactive C3b binds to the virus and CR on CR-bearing cells, leading to the viral entry into cells via phagocytosis, thus

enhancing viral replication and aggravating disease severity [10]. C1q receptors are distributed not only on inflammatory monocytes/macrophages, but also are found on other different cells, including B cells, fibroblasts, neutrophils, and

endothelial cells. This mechanism underlies ADE in both the West Nile virus and HIV.

Figure 2: Complement-mediated ADE

The picture is cited from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6290032/

Besides the common FcR-mediated ADE, the Ebola virus (EBOV) has been known to use the complement component C1q for ADE of infection. This

mechanism is mediated by cross-linking of virus-antibody-C1q complexes to cell surface C1q receptors, resulting in enhanced viral entry into cells. In C1q-dependent ADE, two or more monomer IgG

antibodies protruding from the virus-antibody complex binds to C1q to form the virus-antibody-C1q complex [11]. The virus-antibody-C1q complex combines with the C1q receptor on target

cells, triggers signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K, and some

tyrosine kinases, facilitating viral uptake into the target cells via endocytosis. In some cases, C1q directly binds to viral outer membrane glycoprotein gp41 in the context of HIV infection.

3. Significance of Research about Antibody-dependent Enhancement

The effects of ADE in different viral infections are related to the types of target cells, the differentiation, and maturation of target cells, and the degree of

differentiation. In addition, studies found that whether the effect of ADE occurs in viral infections is also related to the interval between viral infection and passive immunity. If specific antibodies are

injected at the same time as the virus infects animals, most of them can play a reconciled protective effect. Injecting antibodies after infection with the virus, even neutralizing antibodies may enhance the

virulence of the virus.

Having a better understanding of the various mechanisms of ADE plays a key role in determining the antigenic determinants associated with ADE in the virus. Targeting and modifying these

antigenic determinants will help to develop safer and more effective vaccines. More importantly, the nature of the ADE effect is part of the body's immunomodulatory effect. The clear mechanism may

provide an opportunity and direction for the development of new drugs against infectious diseases with clear pathogen infection.

Nevertheless, we can still understand that ADE has far-reaching and

enlightening significance for future immunotherapy, especially vaccine development for infectious diseases caused by pathogen infection. In the future, the era of medicine will still focus on this hot topic

and provide more information to serve the research and development of new drugs.

4. Any Sign of Antibody-dependent Enhancement in SARS-CoV-2 Infection or following COVID-19 Vaccination?

The ADE effect occurring as a result of COVID-19 vaccines has always been the focus of public attention. The latest scientific

research has found that in vitro neutralizing and infection-enhancing RBD or infection-enhancing NTD antibodies protected from SARS-CoV-2 infection in non-human primates and mice [17].

Instead of causing significant disease enhancement such as increased viral load and inflammation, these antibodies exhibited partial protective effects. The authors of the paper believed that SARS-CoV-2

cannot replicate effectively in macrophages (Fc-mediated ADE antibodies mainly enter macrophages) and the protective effects brought by Fc-mediated effectors may contribute to this experiment result. In

summary, the existing evidence is not enough to support that SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 vaccination can induce a significant ADE effect.

Although ADE has been shown up in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV infections,

there have been no confirmed reports of ADE occurring as a result of SARS-CoV-2 infection or following COVID-19 vaccination to date. In human studies, people who were previously infected with

coronaviruses did not experience enhanced disease after being infected with different types of coronaviruses. In the process of COVID-19 vaccine development, scientists adopted several approaches to

avoid ADE. For example, selecting the SARS-CoV-2 protein the least likely cause ADE as antibody target in early vaccine design. Vaccinating animals to see if ADE occurs. Evaluating the condition of humans

and patients in clinical trials. Searching real-world COVID-19 vaccine data for cases.

5. The Solutions for Reducing the Risks of Antibody-dependent Enhancement

ADE has been identified in over 40 types of viruses. It exerts a negative effect on antibody therapy for viral infection and the development of vaccines. One potential

obstacle to antibody-based vaccines and therapies is the risk of exacerbating disease severity through ADE. ADE has been demonstrated to be involved in disease exacerbation in numerous viral infections,

including Zika virus, Ebola virus [12], respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), measles, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV. ADE in

respiratory infections is included in a broader category named enhanced respiratory disease (ERD), which is also associated with non-antibody-based mechanisms such as cytokine cascades and cell-

mediated immunopathology.

Vaccines are a routine medical intervention for healthy individuals, so the phenomena of ADE must be considered during the development of new vaccines to ensure that vaccines are

protective and do not harm the vaccinators. Vaccine developers have sought methods that make ADE less likely.

There are several methods to reduce ADE risks in coronavirus infection. The first is to induce or deliver high doses of potent neutralizing antibodies. Wan et al. indicated that a high dose of

antibodies can suppress the ADE in MERS-CoV without interfering with its anti-viral ability [13]. The second way is to select the viral protein that is the least likely to cause ADE as an antibody

target in early vaccine design. In terms of SARS-CoV-2, choosing specific epitopes within the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike (S) protein as targets for a neutralizing antibody response. It is

inspiring that some early clinical trials have exhibited a strong neutralizing antibody response and a strong Th1 response, rather than the immunopathology-related Th2 response [14]. Taking

advantage of some inhibitors is also beneficial to lower the risk of ADE. Protease inhibitors and Fc inhibitors have been shown to exert inhibitory roles in ADE in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, respectively [13][15][16]. Besides, reducing the risk of ADE in dengue virus by modifying the FcγR binding site on the antibody Fc region.

References

[1] Hawkes R. A. Enhancement of the infectivity of arboviruses by specific antisera produced in domestic fowls [J]. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 1964, 42, 465–482.

[2] Halstead, S. B., Chow, J. & Marchette, N. J. Immunologic enhancement of dengue virus replication [J]. Nat. New Biol. 243, 24–25 (1973).

[3] Halstead, S. B., Shotwell, H. & Casals, J. Studies on the pathogenesis of dengue infection in monkeys [J]. II. Clinical laboratory responses to

heterologous infection. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 15–22 (1973).

[4] Dutta, A, Huang, CT, et al. (2016). Sterilizing immunity to influenza virus infection requires local antigen-specific T cell response in the lungs

[J]. Scientific Reports. 6: 32973.

[5] Wang Q., Zhang L., et al. Immunodominant SARS coronavirus epitopes in humans elicited both enhancing and neutralizing effects on infection

in non-human primates [J]. ACS Infect Dis. 2016; 2: 361-376.

[6] Halstead SB, O'Rourke EJ. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody [J]. J Exp Med

1977;146(1):201–17.

[7] Halstead SB. Immune enhancement of viral infection [J]. Prog. Allergy31, 301–364 (1982).

[8] Taylor A., Foo S. S., et al. Fc receptors in antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infections [J]. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 268, 340–364.

[9] Diebolder CA, Beurskens FJ, et al. Complement is activated by IgG hexamers assembled at the cell surface [J]. Science. (2014) 343:1260–

3.

[10] Takada A., Kawaoka Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection: molecular mechanisms and in vivo implications [J]. Rev. Med. Virol.

2003, 13, 387–398. (complement dependent ADE)

[11] von Kietzell K., Pozzuto T., et al. Antibody-mediated enhancement of parvovirus B19 uptake into endothelial cells mediated by a receptor for

complement factor C1q [J]. J Virol. 2014; 88: 8102-8115.

[12] Takada, A., Feldmann, H., et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection [J]. J. Virol. 77, 7539–7544 (2003).

[13] Y. Wan, J. Shang, et al. Molecular mechanism for antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus entry [J]. J Virol, 94 (5) (2020).

[14] Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults [J]. N Engl J Med

2020; 383:2427-2438.

[15] L. Liu, Q. Wei, et al. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection [J].

JCI Insight, 4 (4) (2019).

[16] Jieqi Wen, Yifan Cheng, et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus [J]. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 100,

November 2020, Pages 483-489.

[17] Dapeng Li, Robert J Edwards, et al. The functions of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing and infection-enhancing antibodies in vitro and in mice and

nonhuman primates [J]. Version 2. bioRxiv. Preprint. 2021 Jan 2 [revised 2021 Feb 18].

CUSABIO team. Does Antibody-dependent Enhancement Occur in SARS-CoV-2 Infection?. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21031.html

Comments

Leave a Comment