Dengue virus

Dengue virus (DENV) is a mosquito-borne, single positive-stranded RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae.[1] Dengue virus has increased dramatically within the last 20 years, becoming one of the worst mosquito-borne human pathogens with which tropical countries have to deal. Dengue is often a leading cause of illness in areas with risk. Forty percent of the world's population, about 3 billion people, live in areas with a risk of dengue. Each year, up to 400 million people get infected with dengue. Approximately 100 million people get sick from infection, and 22,000 die from severe dengue.

The Structure and Important Proteins

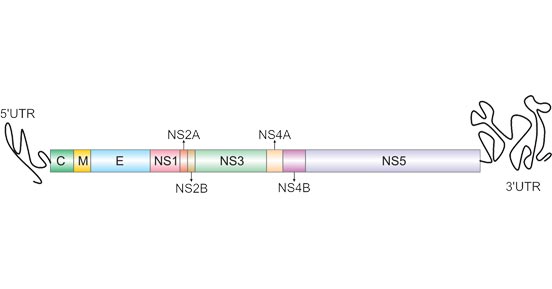

The DENV genome is about 11000 bases of positive-sense, single stranded RNA that codes for three structural proteins (capsid protein C, membrane protein M, envelope protein E) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5).[2] It also includes short noncoding regions on both the 5' and 3' ends.[1]

Figure 1. The Structure Comparison of DENV

The structure of the dengue virus is roughly spherical, with a diameter of approximately 50 nm. The core of the virus is the nucleocapsid, a structure that is made of the viral genome along with C proteins. The nucleocapsid is surrounded by viral envelope, a lipid bilayer that is taken from the host. Embedded in the viral envelope are 180 copies of the E and M proteins that span through the lipid bilayer. These proteins form a protective outer layer that controls the entry of the virus into human cells.

| Protein Name |

Description |

| Capsid protein C |

Plays a role in virus budding by binding to the cell membrane and gathering the viral RNA into a nucleocapsid that forms the core of a mature virus particle. |

| Envelope protein E |

Binds to host cell surface receptor and mediates fusion between viral and cellular membranes. |

| Small envelope protein M |

Play a role in virus budding. Exerts cytotoxic effects by activating a mitochondrial apoptotic pathway through M ectodomain. |

| Non-structural protein 1 |

Involved in immune evasion, pathogenesis and viral replication. |

| Non-structural protein 2A |

Component of the viral RNA replication complex that functions in virion assembly and antagonizes the host immune response. |

| Serine protease subunit NS2B |

Required cofactor for the serine protease function of NS3. |

| Serine protease NS3 |

Displays three enzymatic activities: serine protease, NTPase and RNA helicase. NS3 serine protease, in association with NS2B, performs its autocleavage and cleaves the polyprotein at dibasic sites in the cytoplasm: C-prM, NS2A-NS2B, NS2B-NS3, NS3-NS4A, NS4A-2K and NS4B-NS5. |

| Non-structural protein 4A |

Regulates the ATPase activity of the NS3 helicase activity. NS4A allows NS3 helicase to conserve energy during unwinding. Plays a role in the inhibition of the host innate immune response. |

| Non-structural protein 4B |

Induces the formation of ER-derived membrane vesicles where the viral replication takes place. |

| RNA-directed RNA polymerase NS5 |

Replicates the viral (+) and (-) RNA genome, and performs the capping of genomes in the cytoplasm. Inhibits host TYK2 and STAT2 phosphorylation, thereby preventing activation of JAK-STAT signaling pathway. |

The virus group consists of 4 serotypes that manifest with similar symptoms, DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4.

Related Products

Dengue virus in Disease Research

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. People of all ages who are exposed to infected mosquitoes are possible victims of dengue fever. Typically, people infected with dengue virus are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms such as an uncomplicated fever. [3] Others have more severe illness (5%), and in a small proportion it is life-threatening.

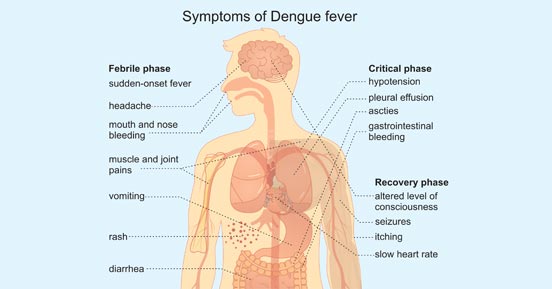

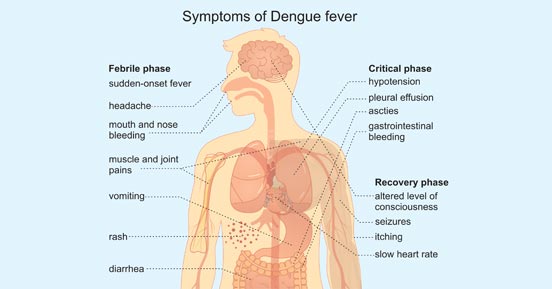

Symptoms typically begin 3 to 14 days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin rash.

In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue, also known as dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in bleeding, low levels of blood platelets and blood plasma leakage, or into dengue shock syndrome, where dangerously low blood pressure occurs.

Figure 2. Symptoms of Dengue Fever

Dengue virus Transmission

-

Through Mosquito Bites

Dengue viruses are spread to people through the bites of infected Aedes mosquitos, particularly A. aegypti. Other Aedes species that transmit the disease include A. albopictus, A. polynesiensis and A. scutellaris. Mosquitoes become infected when they bite a person infected with the virus. Infected mosquitoes can then spread the virus to other people through bites.

-

From mother to child

A pregnant woman already infected with dengue can pass the virus to her fetus during pregnancy or around the time of birth. And dengue spread through breast milk has been reproted.[4] When a mother does have a DENV infection when she is pregnant, babies may suffer from pre-term birth, low birthweight, and fetal distress.

-

Through infected blood

Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation.[5] In countries such as Singapore, where dengue is endemic, the risk is estimated to be between 1.6 and 6 per 10,000 transfusions.[6]

-

Others

Other person-to-person modes of transmission, including sexual transmission, have also been reported, but are very unusual.[7]

References

[1] Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Wilschut J, Smit JM. Dengue Virus Life Cycle: Viral and Host Factors Modulating Infectivity [J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 67 (16), 2773-86.

[2] Dwivedi, VD, Tripathi, IP, Tripathi, RC, et al. Genomics, proteomics and evolution of dengue virus. Briefings in Functional Genomics, July 2017, Pages 217–227.

[3] Senanayake A M Kularatne. Dengue Fever. BMJ, 351, h4661.

[4] Viroj Wiwanitkit. Unusual Mode of Transmission of Dengue. J Infect Dev Ctries, 4 (1), 51-4.

[5] Annelies Wilder-Smith, Lin H Chen, Eduardo Massad, et al. Threat of Dengue to Blood Safety in Dengue-Endemic Countries [J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 15 (1), 8-11.

[6] D Teo, L C Ng, S Lam. Is Dengue a Threat to the Blood Supply [J]. Transfus Med, 19 (2), 66-77.

[7] Lin H Chen, Mary E Wilson. Dengue and Chikungunya Infections in Travelers [J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 23 (5), 438-44.

[8] Maria G Guzman, Scott B Halstead, Harvey Artsob, et al. Dengue: A Continuing Global Threat [J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 8 (12 Suppl), S7-16.