Have you ever handled fixed tissues?

If you prepare tissue sections for immunohistochemistry (IHC), you probably have!

In IHC experiments, tissue samples are often treated with chemical fixation. This process is important to preserve tissue architecture and cytomorphology. However, it may mask tissue antigens and hinder the binding of antibodies, leading to weak or undetectable signals.

Therefore, achieving accurate and reliable IHC results requires more than just a well-performed staining procedure. Due to the fixation process, it also needs to unmask antigens hidden or masked in tissue samples. This process is known as "antigen retrieval".

In this article, we will explore the fundamental principles of antigen retrieval, why it is necessary for IHC, how it works, the different methods available, and the many applications it supports.

Table of Contents

1. What Is Antigen Retrieval?

Antigen retrieval (AR), also known as epitope retrieval, is a laboratory technique used to unmask antigen epitopes in tissue samples, allowing antibodies to bind more effectively during IHC.

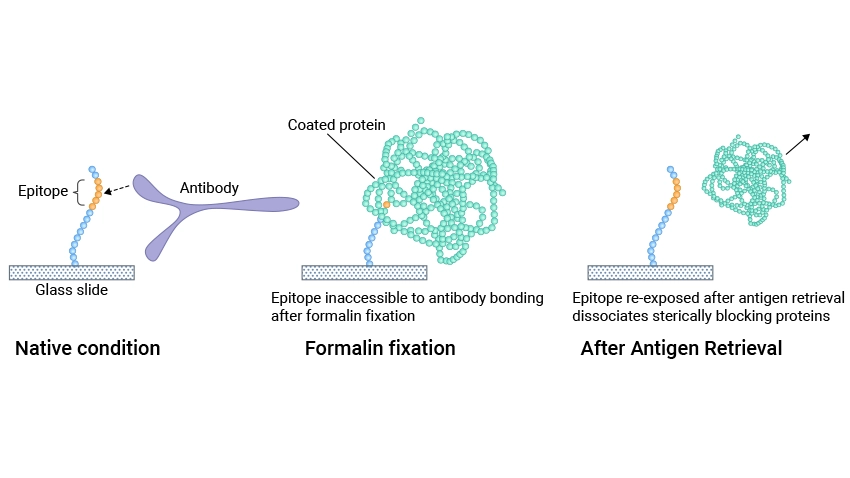

Figure 1. Molecular modeling of antigen retrieval

This picture is cited from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4676902/

2. Why Is Antigen Retrieval Necessary in Immunohistochemistry?

The sample usually undergoes formalin fixation and paraffin embedding (FFPE) to preserve tissue architecture and keep the tissue components in situ without diffusion before IHC. In formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues, fixatives like formaldehyde form chemical crosslinks (methylene bridges) between antigens and unrelated proteins and cover antigen epitopes, which affects the binding between antigens and antibodies during staining procedures [1].

Without antigen retrieval, IHC staining would be less reliable and might result in false negatives or reduced sensitivity. This is particularly problematic in the detection of antigens that may be critical for diagnosing diseases, such as cancer. For example, antigens associated with tumors, like HER2 in breast cancer, require effective antigen retrieval to ensure that IHC staining provides clear, actionable results.

Antigen retrieval breaks these protein formaldehyde cross-links and enables the epitopes to be re-exposed, which enhances the antigen availability for antibody binding, ensuring that the antibody can bind as intended. This increases the sensitivity of the assay and improves the accuracy of the results.

3. How Does Antigen Retrieval Work?

The antigen retrieval principle is thought to be that the cross-links formed during fixation, particularly those produced by formaldehyde, are broken by heating or proteolysis, thus dissociating steric interfering blocking proteins, exposing antigenic sites, and allowing antibody binding [2,3].

4. Different Antigen Retrieval Methods

Antigen retrieval is used to enhance the sensitivity and consistency of immunocytochemical staining. There are two main antigen retrieval methods currently used: proteolytic-induced epitope retrieval (PIER) and heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER).

4.1 Proteolytic-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER)

PIER uses proteolytic enzymes, such as trypsin, pepsin, and protease, to hydrolyze the cross-linked proteins (incubation for 10-15 minutes at 37℃), thus exposing the antigen epitopes and restoring antigenicity [4]. It is frequently employed when the heating retrieval method is ineffective or when the antigen shows significant resistance to heat-induced retrieval.

The effect of PIER is determined by several factors, including the concentration and type of enzyme, incubation conditions (e.g. Time, temperature, and pH), and the fixation duration. The limitations of PIER are the low success rate in restoring immunoreactivity and the risk of compromising both tissue morphology and the target antigens.

4.2 Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER)

HIER is the most common method for antigen retrieval. Heat breaks the formaldehyde-induced cross-links and extends polypeptides to expose epitopes located in the inner portion of antigens or buried by neighboring macromolecules, enabling antibodies to access the target antigens more efficiently [5-7]. It is also thought that HIER acts by eliminating bound calcium ions from the cross-linking sites.

HIER includes water bath heating, microwave heating, and high-pressure heating. The heating devices include microwave ovens (MWO), pressure cookers, vegetable steamers, autoclaves, and water baths. HIER is relatively easy and fast to operate and has a higher success rate than PIER.

If not specified in the antibody data sheet, first try HIER using Tris-EDTA (pH 9) buffer preheated to about 95 ℃ for about 20 minutes. If optimal recovery is not achieved, try other conditions. HIER efficacy is affected by several factors including heating time, temperature, buffer, and pH of the antigen retrieval solution. In general, the higher the temperature the shorter the heating time. The cooling and re-incubation time of the sample after heating may also affect the final effect of HIER. Proper cooling time can make the binding between antigen and antibody more stable.

The appropriate antigen retrieval technique relies on several variables, including the antigen of interest, tissue type, duration and method of fixation, and primary antibody. HIER is generally a more commonly used method, especially when dealing with fixed tissue samples. However, in some cases, PIER may provide better results, especially for some sensitive antibodies or special samples. Some antigens need a combination of heating and enzyme digestion for optimal results.

It is often necessary to optimize the specific conditions of each method, such as temperature, time (heating or incubation), pH, and enzyme concentration, to improve the efficiency of antigen retrieval.

5. Which Applications Can Antigen Retrieval Be Used?

FFPE has been the standard tissue preparation method in surgical pathology and is the basis for most pathological diagnostic criteria. Antigen retrieval has greatly promoted the use of FFPE tissue for IHC, retained the use of existing morphological standards, greatly improved the value of archival FFPE tissue blocks and known follow-up data, and provided a valuable resource for translational clinical research and basic research that cannot be easily replicated.

The broad use of the AR technique in pathology and other morphological fields has shown a significant improvement in IHC staining on archival FFPE tissue sections for various antibodies, particularly in lowering the detection thresholds of immunostaining (enhancing sensitivity) and in retrieving certain antigens, such as Ki-67, MIB1, ER-1D5, androgen receptor, and numerous CD markers, which would otherwise yield negative results in IHC.

5.1 Infectious Disease Studies

Detecting viral or bacterial antigens in tissue samples is critical for diagnosing infectious diseases. Antigen retrieval is often required to unmask the antigens, ensuring the accurate identification of pathogens.

Lean and colleagues showed that enzymatic and heat-mediated antigen retrieval methods can be used to detect SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in FFPE specimens, underscoring the significance of these techniques in the fields of virology and infectious disease diagnostics [8].

5.2 Tumor Marker Detection

Accurate detection of tumor markers is crucial in early diagnosis and staging of cancer. The application of antigen retrieval techniques has significantly improved the detection efficiency and sensitivity of tumor markers such as erbB2, EGFR, and CD117.

Antigen retrieval in IHC enhances antigen accessibility, enabling researchers and clinicians better to identify and characterize specific antigens in cancer cells. Many studies have shown that antigen retrieval not only improves the binding efficiency of antibodies but also reduces the interference of non-specific autofluorescence. For example, some tumor markers may not be effectively recognized in sections without antigen retrieval due to cross-linking, but after antigen retrieval, the signals of these markers are significantly enhanced.

In clinical practice, antigen retrieval has become a standard technique for IHC testing. When analyzing tumor samples, pathologists often first perform antigen retrieval to ensure the accuracy of the test results. This antigen retrieval process is not only applicable to the detection of solid tumors but also to the study of hematological tumors such as lymphoma. This enables doctors to more effectively determine the benign and malignant nature, stage and grade of tumors, thereby providing an important basis for treatment decisions.

Conclusion

The IHC antigen retrieval is a key technique to unlock the potential of tissue samples by restoring access to hidden antigens. It plays an important role in enhancing the precision and accuracy of IHC-based assays. There is no standard method for antigen retrieval, nor is there a single protocol that is ideal for all antigens. Whether to use HIER or PIER, it is advised to empirically optimize the optimum conditions for each sample and tissue type. The best antigen retrieval protocol should be determined through trial and error.

References

[1]Werner M, Chott A, Fabiano A, Battifora H. Effect of Formalin Tissue Fixation and Processing on Immunohistochemistry [J]. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(7):1016–9.

[2]Leong TY, Leong AS (2007). How does antigen retrieval work [J]? Adv Anat Pathol. 14(2):129–31.

[3]Shi S-R, Gu J, Turrens F, Cote RJ, Taylor CR (2000a). Development of the antigen retrieval technique: philosophy and theoretical base. In Shi S-R, Gu J, Taylor CR Antigen Retrieval Techniques: Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Morphology [J]. Natick, MA, Eaton Publishing, 17–39。

[4]Battifora H, Kopinski M (1986). The influence of protease digestion and duration of fixation on the immunostaining of keratins. A comparison of formalin and ethanol fixation [J]. J Histochem Cytochem 34:1095–1100.

[5]Shi SR, Key ME, Kalra KL. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: An enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections [J]. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1991;39:741-748.

[6]Yamashita S, Katsumata O (2017). Heat-induced antigen retrieval in immunohistochemistry: mechanisms and applications [J]. Methods Mol Biol 560:147–161.

[7]Krenacs L, Krenacs T, Stelkovics E, Raffeld M. Heat-induced antigen retrieval for immunohistochemical reactions in routinely processed paraffin sections [J]. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;588:103-19.

[8]Lean FZX, Lamers MM, et al. Development of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation for the detection of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens [J]. Sci Rep. 2020 Dec 14;10(1):21894.

CUSABIO team. Antigen Retrieval: Uncovering Antigen Masking to Improve Immunohistochemistry Results. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21205.html

Comments

Leave a Comment