CD146 is a membrane glycoprotein of a Ca2+-independent cell adhesion molecule that was first identified as a tumor marker because CD146 is highly expressed in melanoma but not in the corresponding normal control group. It is this discovery that has made CD146 a concern in the field of cancer research. At present, a large number of studies have confirmed that CD146 is expressed in melanoma, prostate cancer, breast cancer, liver cancer, urothelial cancer and gynecological tumors and is closely related to the occurrence, metastasis, treatment and prognosis of these tumors. This article introduces CD146 from the aspects of structure, function, signaling pathways and related tumors.

1. The Structure of CD146

CD146, also known as melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM) or cell surface glycoprotein MUC18, is a single-chain transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily (Igsf) member [1]. CD146 is a single-copy gene located on the long arm of human chromosome 11, spanning a chromosomal region of approximately 14kb, encoding a glycosylated protein with a relative molecular mass of 11.3 kDa [2]. The exon-intron structure of the CD146 gene is similar in different species (human, mouse and chicken) [3] [4].

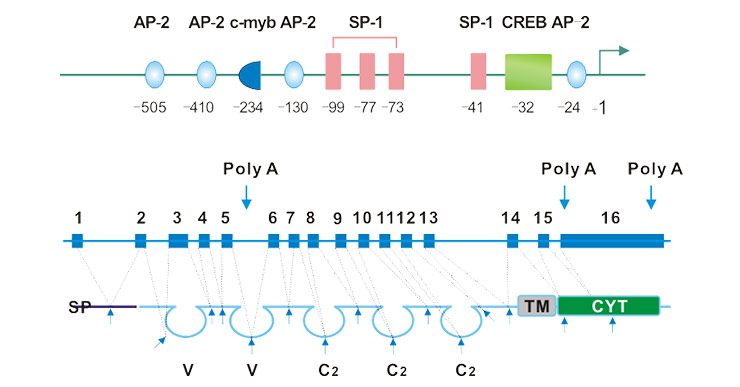

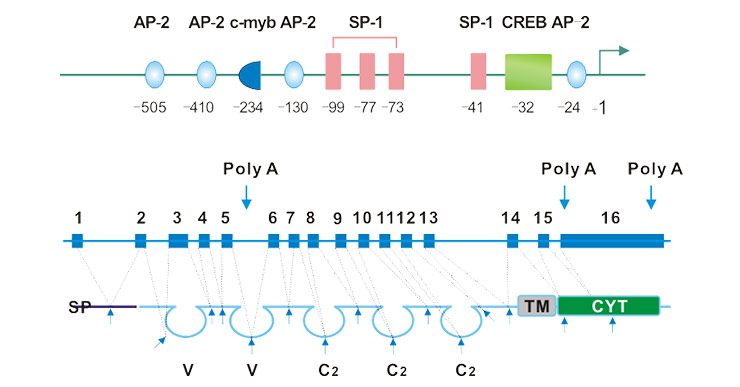

The full length mRNA contains 16 exons. The first exon of hCD146 encodes the 26-bp of 5' UTR region and more than one-third of the signal peptide in the premature hCD146 polypeptide sequence. And the first variable region and the three C-2 constant regions are each encoded by two exons. The second variable region is encoded by three exons. The 16th exon contains a more than 1 kb 5'-UTR region. As shown in Figure 1a, the CD146 gene contains three poly (A) signals [5].

As shown in Figure 1a, the TATA- and CAAT-box-less core promoter of hCD146 starts at the 505-bp upstream of the first ATG, is GC-rich encompasses several consensus binding motifs recognized by transcription factors SP1, AP-2, and CREB [6] [7]. Since the transcription factor AP-2 is critical in embryonic development, and the CD146 promoter region contains multiple AP-2 binding sites, this suggests that CD146 may upregulate its transcriptional level through AP-2 during development.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the exon–intron and promoter structure of the CD146 gene.

The CD146 protein shows high sequence identical among divergent species. As shown in Figure 1b, the mature CD146 protein includes an extracellular region, a transmembrane region, and a cytoplasmic tail region. Its extracellular domain contains a characteristic immunoglobulin domain, including two variable regions and three constant regions (V-V-C2-C2-C2). Its cytoplasmic tail contains a potential protein kinase recognition site, and after activation of CD146, it can form a complex with p59fyn through its cytoplasmic region. As a Src family kinase, p59fyn promotes phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase p125PAK and enhances its association with paxillon.

2. The Function of CD146

As mentioned before, C146 is also known as MCAM. MCAM usually acts as a receptor for the layer-adhesive veneer α4 and is a matrix molecule prevalent in the vessel wall. That is to say, MCAM can be highly expressed in vascular wall component cells, including vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and pericytes.

As a member of the adhesion molecule, MCAM has the fundamental feature of adhesion molecules. It mediates the interaction between cells and the interaction between cells and matrix via binding to its ligands. It has been described in the part of CD146 structure that after activation of CD146, a complex can be formed with p59fyn by its cytoplasmic region. And activated p59fyn further phosphorylates tyrosine kinase p125PAK and binds to paxillon. these also indicates that CD146 can conduct and communicate extracellular to intracellular signals through its intracellular domain, contributing to local Adhesion aggregation, cytoskeletal reorganization and maintenance of cell structure.

As the figure 2 shows, in addition to the adhesion molecule feature of CD146, recent studies have shown that CD146 is active in a variety of cellular physiological processes, including signal transduction, cell migration, mesenchymal stem cell differentiation, angiogenesis, and immune response.

Among them, the most popular with researchers is the flied of tumor formation and metastasis. Tumor growth and diffusion metastasis are closely related to micro-angiogenesis, both primary and metastatic tumors rely on angiogenesis during growth and diffusion [8]. Under normal conditions, angiogenesis will be in equilibrium. This balance will be broken in the tumor microenvironment.

Currently, the mechanism by which CD146 regulates tumor angiogenesis may include activation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), which degrades the basement membrane and extracellular matrix, and activates growth factors, mainly vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is beneficial to Tumor metastasis and tumor angiogenesis [9].

3. Related Signaling Pathways

In addition to its role in cell-cell adhesion, CD146 is also involved in the signaling of endothelial extracellular signals to the cells and is involved in actin cytoskeletal rearrangements. Here, we present several signal paths related to the function of CD146.

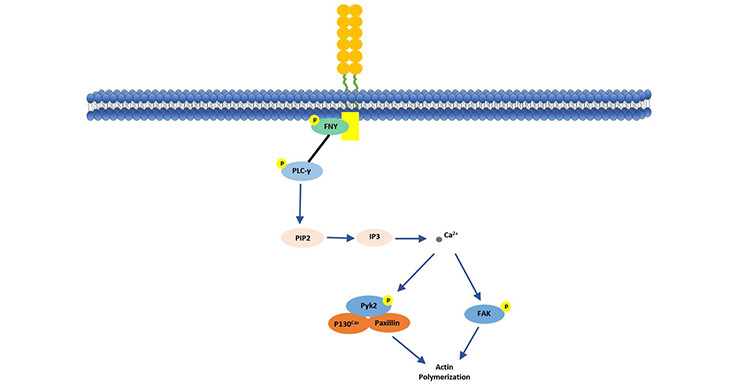

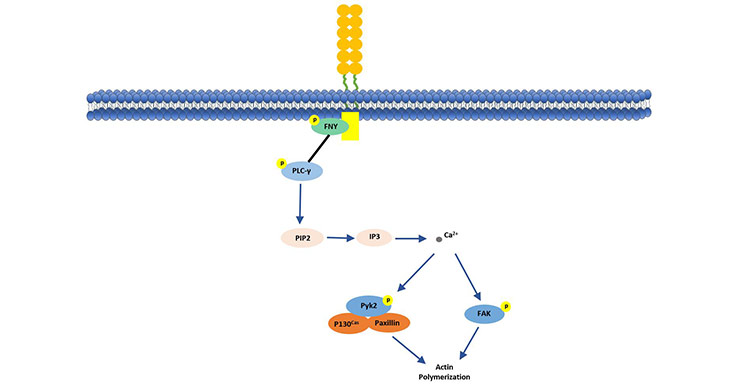

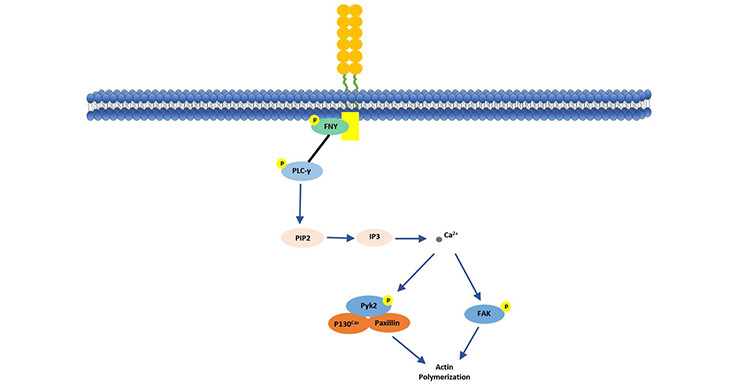

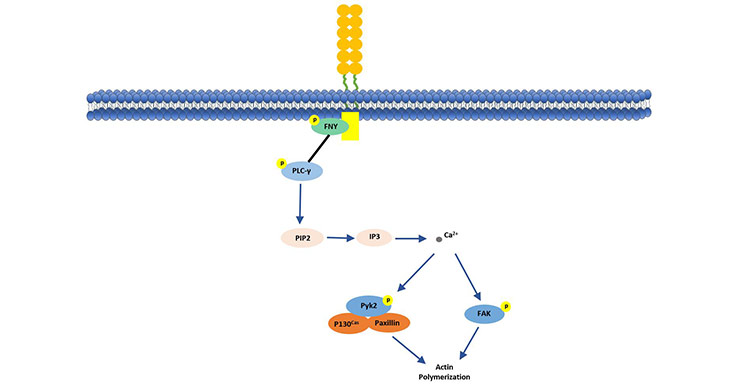

3.1 CD146/ p125PAK

As shown in Figure 2, CD146 initiates a protein kinase phosphorylation cascade by binding to p59fyn (Src family kinase). The activated p59fyn phosphorylates the downstream kinase of PKC-γ, and phosphorylation of the downstream kinase triggers intracellular Ca2+ release. This further activates and induces phosphorylation and binding of P130, Pyk2 and paxillin, while promoting the activation of p125FAK. This CD146-mediated signaling pathway explains the CD146 regulation mechanism of tumor cell invasiveness by transmitting external signals to downstream signaling proteins for cytoskeletal remodeling [10] [11].

Figure 2. CD146 stimulates p125 (FAK) in human endothelial cells

3.2 CD146/Id-1

In cellular signal transduction, CD146 up-regulates Id-1 gene expression. It is thought to be a potential mechanism of melanoma metastasis leading by CD146. Id-1 is a common oncogenic gene of several common malignancies including melanoma. As shown in Figure 4, overexpressed CD146 up-regulated Id-1 by down-regulating ATF-3 which is a transcriptional repressor of Id-1 [12] [13]. However, it is unclear whether CD146 up-regulates Id-1 expression in all malignancies or melanoma.

Figure 3. Expression of Id-1 is regulated by CD146

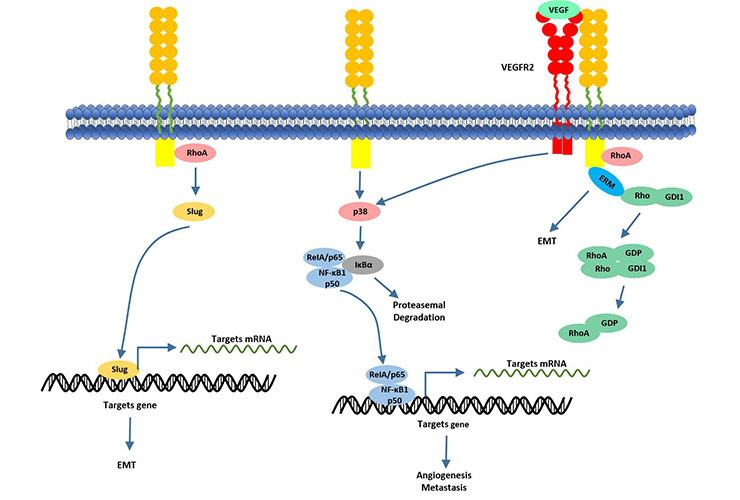

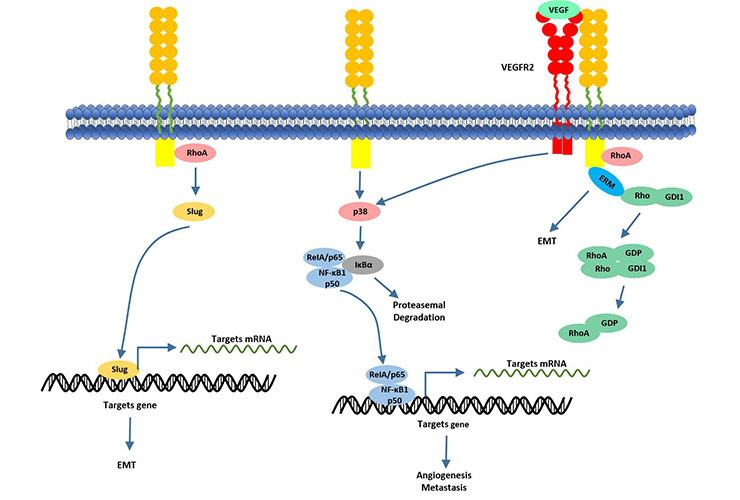

3.3 CD146/NFκB/P38

At present, accumulating studies have reported that CD146 is a new target for tumor angiogenesis. This conclusion has led to a positive exploration of the underlying mechanisms of CD146-induced angiogenesis. Related studies have shown that CD146 forms CD146-CD146 dimers on the cell surface in the CD146-mediated signaling pathway. Overexpressed CD146 enhances EMT through upregulating the transcription factor Slug. The transcription factor Slug controls the transcription of multiple EMT-related elements such as MMP-9 [14].

In addition to acting on Slug, CD146 also can bind to VEGFR-2 as a co-receptor of VEGF ligands, enhancing VEGFR/NFκB signaling [15]. The discovery of this mechanism provides further clear evidence for the critical role of CD146 in cancer metastasis.

Figure 4. CD146 actives NF-κB transcriptional factor via activating of P38 kinase

4. CD146 and Tumor

In recent years, the understanding of CD146 and tumors has gradually expanded from melanoma to other cancers, including prostate cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer and chorionic epithelial cancer.

4.1 CD146 and Melanoma

CD146 was originally cloned from a human melanoma cell cDNA library. A large number of studies have been conducted in malignant melanoma. In the process of melanoma formation, due to the loss of expression of the transcription factor AP-2 (activator protein-2), the AP-2-regulated TATA and CAAT boxes in the CD146 gene are out of control, and the region of rich G+C is over-cloned, resulting in overexpression of CD146.

As the research progressed further, the researchers found that not all malignant melanoma cell lines have CD146 expression. Approximately 70% of melanomas express CD146. The malignant degree of cutaneous melanoma is directly related to the vertical thickness of the lesion. In primary tumors, the expression of CD146 increases with increasing vertical thickness, and CD146 is highly expressed in most advanced or metastatic tumors, but in low metastatic shallow tumors (thickness <0.75 mm), the expression rate is very low.

4.2 CD146 and Prostate Cancer

The incidence of prostate cancer ranks first among male malignant tumors in the world, and its mortality rate is second only to lung cancer. In recent years, the incidence of prostate cancer in American has upsurge. In vitro, Wu et al. used semi-quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis to determine that CD146 mRNA and its protein were less expressed in primary cultured prostate epithelial cells and normal prostate glands, but highly expressed in DUl45, PC-3 and TSU-PR1 prostate cell lines and prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). The expression of CD146 in the four cell lines was conversely correlated with the expression of E-cadherin and α-catenin.

Analysis by immunohistochemistry revealed high expression of CDl46 in PIN and prostate cancer. However, the expression of CD146 is more pronounced in prostate precancerous lesions and prostate cancer epithelium than in normal prostate tissue and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Its positive expression is associated with malignant transformation and progression of the prostate [16].

4.3 CD146 and Breast Cancer

The expression level of CD146 in breast cancer is different from other tumors, and there are different opinions in published reports. Shih et al. reported that 100% (14/14) of normal and benign proliferative mammary ductal epithelium express CD146, and only 17% (12/72) of breast cancer tissues express CD146 [17]. Low expression of CD146 in breast cancer is exactly the opposite of CD146 overexpression in melanoma. In the report of Zaouo et al., it was shown that in human breast cancer, the expression of CD146 enhanced the invasive ability of breast cancer cells, indicating a poor prognosis of patients [18]. In addition, the inconsistent expression levels of CD146 in different cell types of tumors and in different independent studies also reflect the overall complexity of tumor biology.

References

[1] Johnson JP, Rothbacber U, et al. The progression associated antigen MUCl8: A unique member of the immunoglobulin supergone family [J]. Melanoma Ree. 1993, 3(5):337-340.

[2] Shih IM. The role of CDl46 (Mel-CAM) in biology and pathology [J]. J Pathol. 1999, 89(1):4-11.

[3] O. Vainio, D. Dunon, et al. an adhesion molecule expressed by c-kit+ hemopoietic progenitors [J]. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 135:1655-1668.

[4] K. Kohama, Y. Tsukamoto, et al. Molecular cloning and analysis of the mouse gicerin gene [J]. Neurochem. Int. 2005, 46: 465-470.

[5] C. Sers, K. Kirsch, et al. Genomic organization of the melanoma-associated glycoprotein MUC18: implications for the evolution of the immunoglobulin domains [J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993, 8514–8518.

[6] C.S. Mintz-Weber, J.P. Johnson. Identification of the elements regulating the expression of the cell adhesion molecule MCAM/MUC18. Loss of AP-2 is not required for MCAM expression in melanoma cell lines [J]. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275:34672-34680.

[7] Zhaoqing Wang, Xiyun Yan. CD146, a multi-functional molecule beyond adhesion [J]. Cancer Letter. 2013, 330:150-162.

[8] Satyamoorthy K, Muyrers J, et al. Mel-CAM-specific genetic suppressor elements inhibit melanoma growth and invasion through loss of gap junctional communication [J]. Oneogene. 2001, 20(34):4676-4684.

[9] Yan X, Lin Y, et al. A novel anti-CD146 monoclonal antibody, AA98, inhibitors angiogenesis and tumor growth [J]. Blood. 2003, 102(1):194-191.

[10] F. Anfosso, N. Bardin, et al. Activation of human endothelial cells via S-endo-1 antigen (CD146) stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase p125 (FAK) [J]. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273: 26852–26856.

[11] F. Anfosso, N. Bardin, et al. Outside-in signaling pathway linked to CD146 engagement in human endothelial cells [J]. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (2001) 1564–1569.

[12] G. Li, J. Kalabis, et al. Bogenrieder, M. Herlyn, Reciprocal regulation of MelCAM and AKT in human melanoma [J]. Oncogene. 2003, 22:6891–6899.

[13] M. Zigler, G.J. Villares, et al. Expression of Id-1 is regulated by MCAM/MUC18: a missing link in melanoma progression [J]. Cancer Res. 2011, 71:3494–3504.

[14] Q. Zeng, W. Li, et al. CD146, an epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer, is associated with triple-negative breast cancer [J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012, 109:1127-1132.

[15] N. Murukesh, C. Dive, et al. Biomarkers of angiogenesis and their role in the development of VEGF inhibitors [J]. Br. J. Cancer. 2010, 102: 8-18.

[16] Wu GJ, Peng Q, et al.Ectopical expression of hanum MUCl8 increases metastasis of human promate eAlnoer cells [J]. Gene. 2004, 327(2):20l-213.

[17] Shih lM, Hsu MY, et al. The cell-cell adhesion receptor Mel-CAM acts as a tumor suppressor in breast carcinoma [J]. Am J Pathol. 1997, 151(3):745-751.

[18] Zabouo G, lmbert AM, et al. CDl46 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in human breast tumors and with enhanced motility in breast cancer cell lines [J]. Breast Cancer Res. 2009, 11(1):R1-R14.

CUSABIO team. CD146, A Powerful Tumor Marker. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20963.html

Comments

Leave a Comment