Histone modification is a captivating and intricate field of epigenetics that delves into the dynamic changes in chromatin structure. This remarkable process profoundly impacts gene expression, transcriptional regulation, and various cellular functions through chemical alterations of histone proteins. With a complex interplay of writers, erasers, and readers of histone marks, the histone code emerges as an attractive language of epigenetic regulation.

This article explores the fascinating world of histone modifications, describing histone modification’s nature, functional significance, mechanisms, crosstalk, dynamic regulation, and implications in diseases.

1. What Are Histone Modifications?

Histone modifications refer to chemical alterations that occur on the histone proteins, involving the addition of various chemical groups, such as acetyl, methyl, phosphoryl, ubiquitin, and others, to specific amino acid residues on the histones' tails. These modifications do not alter the DNA nucleotide sequence but can regulate the accessibility of DNA to the transcriptional machinery.

2. Function of Histone Modifications

Histone modifications play diverse and essential functions in gene regulation and chromatin structure. They act as a regulatory code that helps to fine-tune gene expression patterns, maintain genome stability, and orchestrate cellular processes during development and in response to environmental cues.

2.1 Gene Activation or Repression

Histone modifications can promote gene activation by relaxing the chromatin structure and making the DNA more accessible to transcriptional machinery. Acetylation of specific lysine residues on histones neutralizes their positive charge, reducing the affinity between histones and DNA and allowing for increased transcriptional activity. Methylation of certain lysine or arginine residues can also enhance gene expression by creating a permissive chromatin environment.

Histone modifications can also repress gene expression by creating a more compact and transcriptionally silent chromatin state. Methylation of specific lysine residues, such as H3K9 and H3K27, is associated with gene repression. These modifications recruit proteins that bind to the modified histones and induce chromatin compaction, inhibiting the binding of transcription factors and other regulatory proteins to the DNA.

2.2 Chromatin Remodeling

Histone modifications play a critical role in the dynamic remodeling of chromatin structure [1]. They act as signals for the recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes, which can alter the positioning and organization of nucleosomes along the DNA. This remodeling process allows for changes in gene accessibility and facilitates the assembly of transcriptional complexes on specific gene promoters or enhancers.

2.3 Epigenetic Memory

Histone modifications contribute to the establishment and maintenance of epigenetic memory. Certain modifications can be inherited through cell divisions and even across generations, contributing to the stable maintenance of gene expression patterns. For example, during development, specific histone modifications can mark genes for either activation or repression, ensuring their appropriate expression patterns in different cell types.

2.4 DNA Repair and Replication

Histone modifications are involved in the regulation of DNA repair and replication processes. They recruit proteins and complexes that are responsible for maintaining genome integrity and coordinating DNA repair mechanisms. Additionally, histone modifications play a role in ensuring proper DNA replication by organizing chromatin structure and facilitating the movement of replication machinery along the DNA strands.

2.5 Developmental Processes

Histone modifications are integral to various developmental processes, including embryogenesis, tissue differentiation, and cell fate determination. They help to establish specific gene expression programs that guide cell differentiation and ensure the appropriate development of different cell types and tissues.

2.6 Environmental Responses

Histone modifications can be dynamically regulated in response to environmental cues and stimuli. External factors, such as stress, nutrition, and exposure to toxins, can induce changes in histone modifications, leading to altered gene expression patterns and cellular responses.

3. Common Histone Modifications and Their Mechanisms

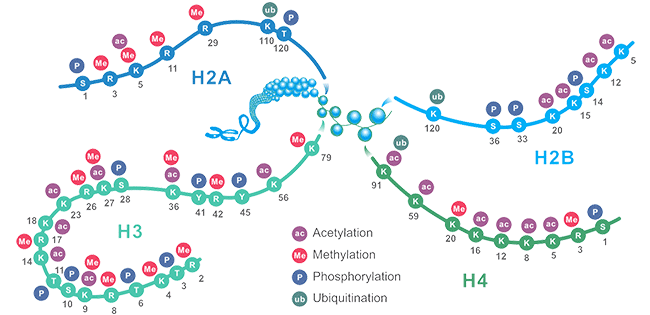

There are numerous types of histone modifications that have been identified and studied to date. Some of the most well-known and extensively studied histone modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and ADP-ribosylation. Different combinations and levels of these modifications on specific residues contribute to the functional diversity and complexity of histone modifications.

Figure1. The Schematic of Common Histone Modification Site

3.1 Histone Acetylation

Histone acetylation is the process in which an acetyl group (COCH3) from acetyl coenzyme A is transferred to lysine residues of histone proteins. Histone acetyltransferases (HAT) and deacetylases (HDACs) are the enzymes responsible for writing and erasing the acetylation of histone tails [2]. Lysine residues within histone H3 and H4 are preferential targets for HAT complexes.

This histone modification is associated with gene activation as it neutralizes the positive charge of lysine, leading to a more relaxed chromatin structure and enhanced transcriptional activity. It is closely involved in the regulation of many cellular processes, including chromatin dynamics and transcription, gene silencing, cell cycle progression, apoptosis, differentiation, DNA replication, DNA repair, nuclear import, and neuronal repression.

Here, we list part of CUSABIO acetylated histone antibodies that can detect different acetylated histone proteins in Table 1.

Table 1. The List of CUSABIO acetylated Histone Antibodies

| Target |

Product Name |

Code |

Tested Species |

Tested Applications |

| H2AFZ |

Acetyl-H2AFZ (K11) Antibody |

CSB-PA010100PA11acHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1B |

Acetyl-HIST1H1B (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010377PA16acHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Acetyl-HIST1H1C (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378PA16acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Acetyl-HIST1H1C (K62) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378PA62acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Acetyl-HIST1H1C (K74) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378OA74acHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Acetyl-HIST1H1C (K84) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378OA84acHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ICC, ChIP |

| HIST1H1E |

Acetyl-HIST1H1E (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010380PA16acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1E |

Acetyl-HIST1H1E (K33) Antibody |

CSB-PA010380PA33acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1E |

Acetyl-HIST1H1E (K51) Antibody |

CSB-PA010380PA51acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1E |

Acetyl-HIST1H1E (K63) Antibody |

CSB-PA010380PA63acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2AG |

Acetyl-HIST1H2AG (K36) Antibody |

CSB-PA010389PA36acHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BB |

Acetyl-HIST1H2BB (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010402OA16acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BB |

Acetyl-HIST1H2BB (K5) Antibody |

CSB-PA010402NA05acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BC |

Acetyl-HIST1H2BC (K108) Antibody |

CSB-PA010403OA108acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BC |

Acetyl-HIST1H2BC (K116) Antibody |

CSB-PA010403OA116acHU |

Human, Rat |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BC |

acetyl-Histone H2B (K120) Antibody |

CSB-PA010403OA120acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Acetyl-HIST1H3A (K36) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA36acHU |

Human, Rat |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Acetyl-HIST1H3A (K37) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA37acHU |

Human, Rat |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Acetyl-HIST1H3A (K79) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA79acHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Acetyl-HIST1H3A (K9) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418PA09acHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Acetyl-HIST1H3A (T22) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA22acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K12) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429PA12acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K12) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429OA12acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429NA16acHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429PA16acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K31) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429OA31acHU |

Human, Rat |

ELISA, WB, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K5) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429PA05acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K79) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429OA79acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Acetyl-HIST1H4A (K8) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429PA08acHU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

3.2 Histone Methylation

Histone methylation specifically occurs on histone H3 and H4 at distinct lysine or arginine residues. Lysine can be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated, and arginine can be mono- or di-methylated (asymmetric or symmetric) [3,4]. It causes transcription repression or activation, depending on the specific tail residue methylated and its degree of methylation. For example, methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4), H3K36, H3K79, or arginine 17 (H3R17) is associated with transcriptional activation [5]. Conversely, methylation of histone H3 at H3K9, H3K27, or histone H4 at H4K20 is often linked to transcriptional repression.

Histone methylation influences gene expression by recruiting various transcription factors, rather than by directly altering chromatin structure [6].

Here, we list part of CUSABIO methylated histone antibodies that can detect different methylated histone proteins in Table 2.

Table 2. The List of CUSABIO Methylated Histone Antibodies

| Target |

Product Name |

Code |

Tested Species |

Tested Applications |

| H1F0 |

Mono-methyl-H1F0 (K101) Antibody |

CSB-PA010087OA101me1HU |

Human, Rat |

ELISA, WB, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| H1F0 |

Mono-methyl-H1F0 (K81) Antibody |

CSB-PA010087OA81me1HU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| H2AFZ |

Mono-methyl-H2AFZ (K4) Antibody |

CSB-PA010100OA04me1HU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| H3F3A |

Di-methyl-H3F3A (K79) Antibody |

CSB-PA010109OA79me2HU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H1C (K118) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378PA118me1HU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H1C (K186) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378PA186me1HU |

Human, Mouse, Rat |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Di-methyl-HIST1H1C (K45) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378OA45me2HU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ICC, IP, ChIP |

| HIST1H1C |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H1C (K96) Antibody |

CSB-PA010378OA96me1HU |

Human, Mouse, Rat |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1E |

Di-methyl-HIST1H1E (K16) Antibody |

CSB-PA010380PA16me2HU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2AG |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H2AG (K9) Antibody |

CSB-PA010389OA09me1HU |

Human |

ELISA, ICC, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H2AG |

Di-methyl-HIST1H2AG (R29) Antibody |

CSB-PA010389OA29me2HU |

Human |

ELISA, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BC |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H2BC (K12) Antibody |

CSB-PA010403OA12me1HU |

Human, Mouse, Rat |

ELISA, WB, ICC, ChIP |

| HIST1H2BC |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H2BC (K20) Antibody |

CSB-PA010403OA20me1HU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, ChIP |

| HIST1H4A |

Mono-methyl-HIST1H4A (K5) Antibody |

CSB-PA010429OA05me1HU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

3.3 Histone Phosphorylation

Histone phosphorylation involves the addition of phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues on the histone tails. It is associated with signaling pathways and plays a role in chromatin remodeling, transcriptional activation, and cellular processes such as the cell cycle and DNA damage response.

Histone phosphorylation is regulated by two types of enzymes with contrasting actions. Kinases add phosphate groups, while phosphatases remove them. Phosphorylated histones serve several functions, including DNA damage repair, the regulation of chromatin compaction during mitosis and meiosis, apoptosis, and the modulation of transcriptional activity [7,8]. The best-known function of histone phosphorylation takes place during cellular response to DNA damage when phosphorylated histone H2A(X) demarcates large chromatin domains around the site of DNA breakage [9].

Here, we list part of CUSABIO phosphorylated histone antibodies that can detect different phosphorylated histone proteins in Table 3.

Table 3. The List of CUSABIO phosphorylated Histone Antibodies

| Target |

Product Name |

Code |

Tested Species |

Tested Applications |

| H2AFX |

Phospho-H2AFX (S139) Antibody |

CSB-PA010097OA139phHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1B |

Phospho-HIST1H1B (T154) Antibody |

CSB-PA010377PA154phHU |

Human |

ELISA, WB, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H1D |

Phospho-HIST1H1D (T179) Antibody |

CSB-PA010379OA179phHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Phospho-HIST1H3A (S28) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA28phHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Phospho-HIST1H3A (T6) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA06phHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

| HIST1H3A |

Phospho-HIST1H3A (T80) Antibody |

CSB-PA010418OA80phHU |

Human |

ELISA, IF, ChIP |

3.4 Histone Ubiquitination

Histones can undergo extensive modifications on lysine residues through the addition of ubiquitin, which is regulated by a cascade of enzymes, including E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligase enzymes. Conversely, deubiquitinating enzymes control the removal of ubiquitin from histones. This dynamic regulation of histone ubiquitination plays a crucial role in maintaining genome stability, regulating the cell cycle, and modulating transcriptional processes.

3.5 Histone Sumoylation

Histone sumoylation involves the covalent attachment of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) groups to specific lysine residues on histone proteins. Sumoylation can occur on various histone proteins, including histone H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, as well as their variants. Similar to ubiquitination, SUMOylation is a multi-step process mediated by the sequential action of enzymes, including SUMO-activating enzyme (E1), SUMO-conjugating enzyme (E2), and SUMO ligases (E3).

Histone sumoylation plays a critical role in regulating chromatin structure by inhibiting the formation of certain higher-order chromatin structures. It acts as a key signal for the recruitment of factors involved in both gene activation and repression.

3.6 Histone ADP-ribosylation

Histone ADP-ribosylation is the addition of ADP-ribose moieties to various amino acids, including glutamate, aspartate, and arginine residues on the histone tails. ADP-ribosylation is catalyzed by ADP-ribosyltransferases (ARTs) and is a reversible process regulated by ADP-ribosyl hydrolases.

4. Crosstalk between Different Histone Modifications

In 2000, Strahl and Allis proposed the "histone code", which is formed by the interaction of single or multi-histone modification with each other [10]. Histone modifications often exhibit crosstalk, influencing each other's effects. This crosstalk between different histone modifications adds another layer of complexity to the regulation of chromatin structure and gene expression.

For example, phosphorylation of serine 10 on histone H3 (H3S10ph) can hinder the trimethylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 (H3K9me3) while promoting the acetylation of lysine 16 on histone H4 (H4K16ac) [11].

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Walter et al. discovered that the Snf1 kinase phosphorylated serine 10 (S10) on histone H3 accelerating the acetylation of H3 lysine 14 (K14) by the Gcn5 acetyltransferase, which increased the interaction between H3 with the 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1 and Bmh2 during gene activation [12].

Daujat et al. found that in mammalian cells, acetylation of H3 on K18 and K23 stimulates arginine 17 (R17) methylation by the CARM1 methyltransferase, leading to the activation of estrogen-responsive genes [13].

Furthermore, histone modification crosstalk can also influence the loss of specific modifications. For instance, in budding yeast, Lee and Shilatifard demonstrated that the RNA polymerase II-associated Set2 methyltransferase methylates H3K36, establishing a mark that directs nucleosomes for H3 and H4 deacetylation by the Rpd3S deacetylase complex following RNA polymerase passage [14].

5. Dynamic Regulation of Histone Modifications

Histone modifications are dynamically regulated by a complex interplay of enzymes or proteins known as "writers," "erasers," and "readers." Writers enzymatically modify specific amino acid residues on histones, including HATs, HMTs/KMTs, PRMTs, kinases, and ubiquitin ligases. Erasers remove or reverse these modifications, including HDACs, HDMs/KDMs, phosphatases, and DUBs. Readers including bromodomains, chromodomains, or Tudor domains can recognize and identify those modified histone residues and then translate these signals into distinct downstream effects. For instance, bromodomains selectively target acetyllysine residues. Many chromodomains bind methylated lysines and Tudor domains bind methylated arginines. The interplay between histone modifications and regulatory proteins influences chromatin structure, gene expression, and cellular processes.

6. Role of Histone Modifications in Diseases

Imbalances in the activation or inactivation of histone modifications can disrupt gene expression programs and contribute to the pathogenesis linked to transcriptome abnormalities. Therefore, mutations in genes associated with histone modifications may result in the onset and progression of various diseases, encompassing cancers, autoimmune disorders, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative conditions.

Abnormal histone modifications, such as increased histone acetylation or altered histone methylation patterns, can contribute to oncogenesis. A study demonstrated the depletion of H4K16ac and H4K20me3 in various cancer types, establishing these two histone marks as distinct characteristics of tumors and the correlation of H4K16ac with tumor progression [15,16]. Seligson DB et al. found that H3K18ac, H4K12ac, and H4R3me2 were positively associated with prostate cancer grade [17].

Epigenetic dysregulation, including altered histone modifications, has been implicated in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [18] and systemic lupus erythematosus [19]. Changes in histone acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation can influence immune cell function, cytokine production, and immune response regulation, contributing to the development of autoimmune disorders.

Histone modifications have been linked to neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Huntington's disease [20,21]. Altered histone acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation patterns have been associated with neuroinflammation, neuronal cell death, and impaired synaptic plasticity, which are hallmark features of these diseases.

Histone modifications can impact cardiovascular health by regulating gene expression patterns in cardiac cells and vascular tissues. Dysregulation of histone acetylation and methylation has been implicated in cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure, atherosclerosis, and vascular remodeling.

7. Summary

Histone modifications are crucial epigenetic marks that regulate gene expression and chromatin structure. These modifications act as a dynamic language, forming a histone code that regulates diverse cellular processes, including development, differentiation, and disease progression. Understanding their nature, functional significance, mechanisms, crosstalk, dynamic regulation, and implications in diseases opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions and enhances our understanding of the intricate world of histone modifications in health and disease.

Understanding the relationship between histone modifications and disease provides valuable insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. By targeting specific histone modifications, it may be possible to restore normal gene expression patterns and alleviate the impact of histone modification dysregulation in various diseases.

References

[1] Bannister, A. J. & Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications [J]. Cell Res. 21, 381–395 (2011).

[2] Marmorstein, R. & Zhou, M. M. Writers and readers of histone acetylation: structure, mechanism, and inhibition [J]. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6, a018762 (2014).

[3] Bannister, A. J., Schneider, R., and Kouzarides, T. (2002). Histone methylation [J]. Cell 109, 801–806.

[4] Bannister, A. J., and Kouzarides, T. (2005). Reversing histone methylation [J]. Nature 436, 1103–1106.

[5] Bauer, U. M., Daujat, S., et al. Methylation at arginine 17 of histone H3 is linked to gene activation [J]. EMBO Rep. 3, 39–44 (2002).

[6] Klose, R. J., and Zhang, Y. (2007). Regulation of histone methylation by demethylimination and demethylation [J]. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 307–318.

[7] Rossetto D, Avvakumov N, Côté J. Histone phosphorylation: a chromatin modification involved in diverse nuclear events [J]. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1098–108.

[8] Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications [J]. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–95.

[9] Ye Zhang, Karen Griffin, et al. Phosphorylation of Histone H2A Inhibits Transcription on Chromatin Templates [J]. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279(21):21866-72.

[10] Latham JA, Dent SY. Cross-regulation of histone modifications [J]. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1017–24.

[11] Zippo, A.; Serafini, R.; et al. Histone Crosstalk between H3S10ph and H4K16ac Generates a Histone Code That Mediates Transcription Elongation [J]. Cell 2009, 138, 1122–1136.

[12] Walter W, Clynes D, et al. 14-3-3 interaction with histone H3 involves a dual modification pattern of phosphoacetylation [J]. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Apr;28(8):2840-9.

[13] Sylvain Daujat, Uta-Maria Bauer, et al. Crosstalk between CARM1 methylation and CBP acetylation on histone H3 [J]. Curr Biol. 2002 Dec 23;12(24):2090-7.

[14] Jung-Shin Lee and Ali Shilatifard. A site to remember: H3K36 methylation a mark for histone deacetylation [J]. Mutat Res. 2007 May 1;618(1-2):130-4.

[15] Fraga MF, Ballestar E, et al. Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer [J]. Nat Genet. 2005;37:391-400.

[16] Tryndyak VP, Kovalchuk O, Pogribny IP. Loss of DNA methylation and histone H4 lysine 20 trimethylation in human breast cancer cells is associated with aberrant expression of DNA methyltransferase 1, Suv4-20h2 histone methyltransferase and methyl-binding proteins [J]. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:65-70.

[17] Seligson DB, Horvath S, et al. Global histone modification patterns predict risk of prostate cancer recurrence [J]. Nature. 2005;435:1262-1266.

[18] Araki, Y. et al. Histone methylation and STAT-3 differentially regulate interleukin-6-induced matrix metalloproteinase gene activation in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts [J]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 1111–1123 (2016).

[19] Hu N, Qiu X, Luo Y, Yuan J, Li Y, Lei W, et al. Abnormal histone modification patterns in lupus CD4+ T cells [J]. J Rheumatol (2008) 35:804–10.

[20] Santana DA, Smith MAC, Chen ES. Histone Modifications in Alzheimer's Disease [J]. Genes (Basel). 2023 Jan 29;14(2):347.

[21] Park, J., Lee, K., Kim, K. et al. The role of histone modifications: from neurodevelopment to neurodiseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 217 (2022).

CUSABIO team. Unraveling the Dynamic World of Histone Modifications: Implications in Gene Regulation and Disease Pathogenesis. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20829.html

Comments

Leave a Comment