Skin cancer is the most common of all human cancers. In 2020, more than 100,000 people in the U.S. are expected to be diagnosed with some type of the disease. Nearly 7,000 are expected to die. There are three major types of skin cancers: basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma. Among of them, melanoma accounts for only about 1% of skin cancers but causes a large majority of skin cancer deaths. So what is melanoma? How does melanoma develop? And how to diagnose it?

1. What is Melanoma?

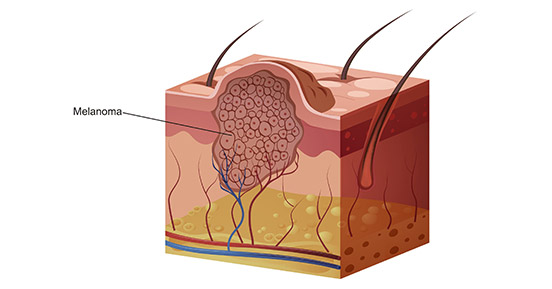

Melanoma, usually referred to as malignant melanoma, is a highly malignant tumor derived from melanocytes which control the pigment in your skin. The figure 1 shows melanoma cells extending from the surface of the skin into the deeper skin layers. Melanoma occurs mostly in the skin, but also in the mucous membrane and viscera, accounting for about 3% of all tumors. Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer and strikes tens of thousands of people around the world each year. The number of cases is rising faster than any other type of solid cancer [1].

Figure 1. a diagram of melanoma

In 2020, the American Cancer Society's estimates that there will have approximately 100,350 new melanomas diagnosed (about 60,190 in men and 40,160 in women), and 6,850 deaths from melanoma (about 4,610 men and 2,240 women). The rates of melanoma have been rising rapidly over the past few decades, but this has varied by age. So how does melanoma develop?

2. How does Melanoma Develop?

Melanoma occurs when something goes wrong in melanocytes, the cells producing the pigment melanin. Normally, skin cells develop in a controlled and orderly way — healthy new cells push older cells toward to the surface of skin, where they die and eventually fall off. But when some cells undergo DNA damage, new cells may start to grow out of control and can eventually form a mass of cancerous cells. So what damages DNA in skin cells?

In fact, it isn't still clear. It may be a combination of factors, including environmental and genetic factors, causes melanoma. Currently, doctors believe exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun and from tanning lamps and beds is the leading cause of melanoma. UV light doesn't cause all melanomas, especially those that occur in places on your body that don't receive exposure to sunlight. This suggests that other factors may contribute to your risk of melanoma. Regarding to the risk factors of melanoma, continuing to read…

3. What are the Risk Factors of Melanoma?

As mentioned previously, exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and other sources of ultraviolet light, like tanning beds, is a very important risk factor. In addition to the ultraviolet light, factors that may increase risk of melanoma include:

-

Race. The American Cancer Society states that the lifetime risk of developing melanoma is about 2.6% for white people, 0.1% for Black people and 0.6% for Hispanic people. Accumulating evidence has revealed that melanoma in white people is 20 times more common than black people.

-

A family history of melanoma. If a close relative (such as a parent, child or sibling) has had melanoma, you may have a greater chance of developing melanoma.

-

Weakened immune system. People with weakened immune systems also have an increased risk of melanoma and other skin cancers. Your immune system may be impaired if you take medicine to suppress the immune system, such as after an organ transplant, or if you have a disease that impairs the immune system, such as AIDS.

-

Age. The risk of melanoma grows as you age. The average age at diagnosis is 65, even though it's one of the most common cancers among young adults.

4. What are the Mechanisms of Melanoma?

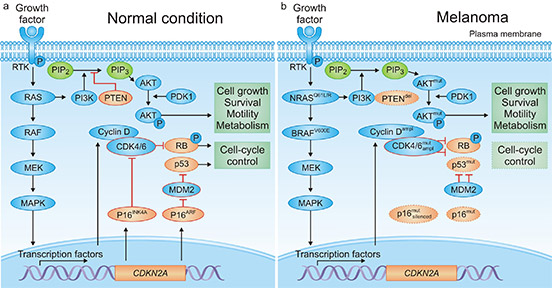

Melanoma caused by transformation of melanocytes requires a complex interaction of exogenous and endogenous events. There are tremendous progress has been reported to make in unravelling the genetic basis of melanoma [5] [6] [7]. As the figure 2a shows, under normal conditions, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3‑kinase (PI3K)–AKT signaling permit balanced control of basic cellular functions, including cell cycle regulation, survival, motility and metabolism.

However, in melanoma, several genetic alterations depicted in the figure 2b are frequently observed, leading to constitutive pathway activation (indicated by thick arrows) and loss of cellular homeostasis. Malignant transformation can require combinations of genetic defects. The functional consequences of genetic events determine whether mutations can coexist or remain mutually exclusive. For example, mutations in NRAS and BRAF occur very rarely in the same melanoma cell, whereas combined genetic alterations of BRAF and PTEN are common.

Figure 2. signaling pathways in melanoma

*this diagram is derived from publication on Nature Reviews [4].

References

[1] Karl Smart, Ian Pope, Robert Sullivan. MELANOMA [J]. Nature. 2014, 515: S109.

[2] Ribas A, Slingluff CL, Rosenberg SA. Cutaneous Melanoma [J]. Principles and Practice of Oncology. 2015. pp. 1346-94.

[3] Coricovac D, Dehelean C, Moaca EA, et al. Cutaneous melanoma long road from experimental models to clinical outcome: a review [J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19:1566.

[4] Dirk Schadendorf, David E. Fisher, Claus Garbe, et al. Melanoma [J]. NATURE REVIEWS. 2015.

[5] Bastian, B. C. The molecular pathology of melanoma: an integrated taxonomy of melanocytic neoplasia [J]. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2014, 9, 239–271.

[6] Sheppard, K. E. & McArthur, G. A. The cell-cycle regulator CDK4: an emerging therapeutic target in melanoma [J]. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5320–5328.

[7] Shi, J. et al. Rare missense variants in POT1 predispose to familial cutaneous malignant melanoma [J]. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 482–486.

CUSABIO team. Melanoma, the Most Serious Type of Skin Cancer. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21006.html

Comments

Leave a Comment