3. Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors

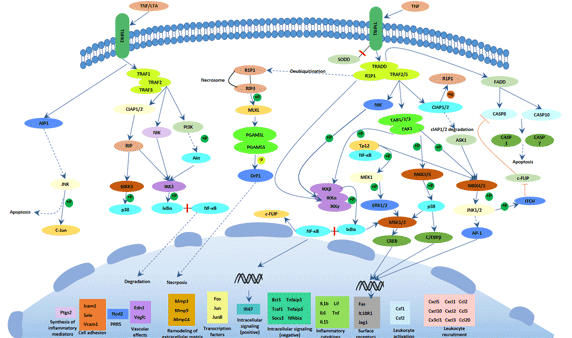

A tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitor is a pharmaceutical drug that suppresses the physiologic response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which is part of the inflammatory response. TNF is involved in autoimmune and immune-mediated disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa and refractory asthma, so TNF inhibitors may be used in their treatment. The inhibitor, including etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, and golimumab, all bind to the cytokine TNF and inhibit its interaction with the TNF receptors[2].

As a cytokine, TNF is involved with the inflammatory and immune response and can bind to TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) or TNF receptor 2 (TNFR2). It occurs in numerous forms, both monomeric and trimeric, as well as soluble and transmembrane[3]. Etanercept is a fusion protein of two TNFR2 receptor extracellular domains and the Fc fragment of human IgG1. It inhibits the binding of both TNF-alpha and TNF-beta to cell surface TNFRs. Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that includes a murine variable region and constant human region. It binds to the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNF-alpha and inhibits the binding of TNF-alpha to TNFR[4].

The important side effects of TNF inhibitors include lymphomas, infections, congestive heart failure, demyelinating disease, a lupus-like syndrome, induction of auto-antibodies, injection site reactions, and systemic side effects[5].

5. Tumor Necrosis Factor and Diseases

Accumulating evidences have revealed that dysregulation of TNF production was implicated in a variety of human diseases including Alzheimer's disease[7], cancer[8], major depression[9], psoriasis[10] and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Its complex functions in the immune system include the stimulation of inflammation, cytotoxicity, the regulation of cell adhesion, and the induction of cachexia.

Tumor Necrosis Factor and Cancer

TNF-α is frequently detected in biopsies from human cancer, produced either by epithelial tumor cells, as for instance in ovarian and renal cancer; or stromal cells, as in breast cancer[11]. Cancer cell or stromal cell production of TNF-α is involved in the development of a range of experimental tumors, is partially responsible for NF-κB activation in initiated tumor cells and for the cytokine network in found in human cancer[12].

There are several known consequences of TNF-α production by cancer cells that begin to explain its role in cancer progression. As stated above ovarian cancer cell lines, but not normal ovarian surface epithelial cells, produce pg quantities of TNF-α protein and that there were differences in TNF-α mRNA stability between normal and malignant cells[13]. This endogenous TNF-α correlates with increased cancer cell expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12, in both cell lines and biopsies of disease[14]. TNF-α up-regulated CXCR4 expression, cancer cell migration and production of other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by the ovarian epithelial cells. CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 are implicated in metastases and tumor cell survival in a wide range of cancers[15].

Anti-TNF therapy has shown only modest effects in cancer therapy. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma with infliximab resulted in prolonged disease stabilization in certain patients. Etanercept was tested for treating patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer showing prolonged disease stabilization in certain patients via downregulation of IL-6 and CCL2. On the other hand, adding infliximab or etanercept to gemcitabine for treating patients with advanced pancreatic cancer was not associated with differences in efficacy when compared with placebo[16].

Tumor Necrosis Factor and Inflammation

As TNF plays a key role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases such as Crohn's disease (CD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a new class of drugs has been developed in an attempt to neutralise its biological activities.

Tumor Necrosis Factor and rheumatoid arthritis

The primary cellular elements in the RA inflammatory process that cause synovitis and other systemic manifestations are the CD4+ lymphocyte, macrophage, and synovial fibroblasts. The cells produce numerous cytokines, of which interleukin (IL)–1, IL-6, and TNF are arguably the most important in the RA inflammatory cascade. The important role of TNF-α has also been verified in clinical trials of TNF inhibitors. TNF-α, a homodimer produced primarily by macrophages/monocytes, is an excellent promoter of RA inflammation. Acting through a p55 or p75 receptor, it stimulates other cells to produce various inflammatory cytokines, for example, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-18, and interferon (IFN)–γ[17].

Tumor Necrosis Factor and Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease (CD) is chronic inflammatory conditions characterized by episodes of remission and flare-ups that have a major impact on the patient's physical, emotional and social well-being. Similar to its role in rheumatoid arthritis, TNFα has also been shown to be crucial in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease.

TNF is a crucial mediator in driving inflammatory processes in the gut. It is produced by a variety of mucosal cells, mainly macrophages and T cells, as a preform on the plasma membrane. In addition, Paneth cells in CD affected segments of the terminal ileum were shown to strongly express TNF RNA in contrast to Paneth cells in normal tissue, indicating an induction under pathogenic conditions. The transmembrane precursor form (mTNF), a homotrimer of 26 kDa subunits, is cleaved by the matrixmetalloproteinase TNF alpha converting enzyme (TACE/Adam17) into a soluble form. The expression of mTNF by CD14+ macrophages has been reported to be relevant in CD)[18].

Anti-tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNFα) antibodies have been used as a potent therapy for CD. These particular agents are effective not only for CD patients who have never undergone surgery but also for those who have received surgery. In fact, fewer endoscopic recurrences were observed in patients who received anti-TNF agents after surgery than in those who did not.6 In the meanwhile, a report suggested that no significant difference in the endoscopic recurrence rate was observed between biological and conventional therapy after ileocecal resections in CD patients. In this context, the efficacy of anti-TNF agents for postoperative CD patients have been evaluated in patients who had no history of undergoing anti-TNFα antibody treatment prior to surgery. Because primary nonresponses or secondary loss of responses can frequently occur in CD patients who are administered anti-TNF agents, a substantial portion of patients who require anti-TNF agents after surgery receive the agents also prior to surgery in clinical practice[19][20].

References

[1] Carl F. Ware. TNF Superfamily 2008[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2008 (3-4): 183–186

[2] Valerie Gerriets1; Steve S. Bhimji2. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), Inhibitors[J]. StatPearls Publishing, 2018 Jan

[3] Meroni PL, Valentini G, et al. New strategies to address the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors: A systematic analysis[J]. Autoimmun Rev. 2015 (9): 812-29

[4] Komaki Y, Yamada A, et al. Efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of biosimilars of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents in rheumatic diseases; A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Autoimmun. 2017 (79): 4-16

[5] N Scheinfeld. A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab[J]. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 2004 (15): 280–294

[6] Arianne L. Theiss, James G. Simmons, et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Increases Collagen Accumulation and Proliferation in Intestinal Myofibroblasts via TNF Receptor 2[J]. The journal of biological chemistry, 2005 (43): 36099 -36109

[7] Swardfager W, Lanctôt K, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2010 (68): 930–941

[8] Locksley RM, Killeen N, et al. "The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology[J]. Cell, 2001 (104): 487–501

[9] Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2010 (5): 446–457

[10] Victor FC, Gottlieb AB. TNF-alpha and apoptosis: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis[J]. Drugs Dermatol, 2002 (3): 264–75

[11] Balkwill, F. (2002). Tumor necrosis factor or tumor promoting factor[J]. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, 2002 (13): 135–141

[12] Galban, S., Fan, J., et al. von Hippel-Lindau protein-mediatedrepression of tumor necrosis factor alpha translation revealed through use of cDNA arrays[J]. Molecular & Cellular Biology, 2003 (23): 2316–2328

[13] Tsan, M.-F. Toll-like receptors, inflammation and cancer[J]. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 2005 (16): 32–37

[14] Kulbe, H., Hagermann T, et al. The inflammatory cytokine TNF-a upregulates chemokine receptor expression on ovarian cancer cells[J]. Cancer Research, 2005 (65): 10355–10362

[15] Balkwill, F. The significance of cancer cell expression of CXCR4[J]. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 2004 (14): 171–179

[16] Korneev KV, Atretkhany KN, et al. TLR-signaling and proinflammatory cytokines as drivers of tumorigenesis[J]. Cytokine, 2017 (89): 127–135

[17] Ma X, Xu S. TNF inhibitor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Biomed Rep, 2012 (2): 177–184.

[18] Narayanan Parameswaran, Sonika Patial. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Signaling in Macrophages[J]. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr, 2010 (2): 87–103.

[19] Ulrike Billmeier, Walburga Dieterich, et al. Molecular mechanism of action of anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016 (42): 9300–9313

[20] Konstantinos Papamichael, Adam S Cheifetz. Defining and predicting deep remission in patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy[J]. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 (34): 6197–6200

Comments

Leave a Comment