[1] Vaughan DW, Peters A (1974).Neuroglial cells in the cerebral cortex of rats from young adult to old age: an electron microscopy study [J]. J. Neurocytol.3, 405-429.

[2] Banati R (2003). Neuropathological imaging: in vivo detection of glial activation as a measure of disease and adaptive change in the brain [J]. Brit. Med. Bul.65, 121-131.

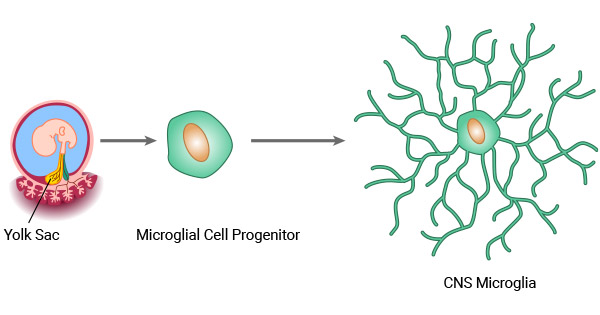

[3] Gomez Perdiguero E., Schulz C., Geissmann F. (2013). Development and homeostasis of “resident” myeloid cells: the case of the microglia [J]. Glia 61, 112–120.

[4] Kreutzberg G. W. (1996) Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS [J]. Trends Neurosci.19, 312-318.

[5] Stence N., Waite M., Dailey E. (2001) Dynamics of microglial-activation: a confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices [J]. Glia.33, 256-266.

[6] Giordana MT, Attanasio A, et al. (1994) Reactive cell proliferation and microglia following injury to the rat brain [J]. Neuropathol.Appl. Neurobiol.20, 163-174.

[7] Dihne M, Block F, Korr H, Topper R (2001). Time course of glial proliferation and glial apoptosis following excitotoxic CNS injury [J]. Brain Res. 902, 178-189.

[8] Eugenin EA, Eckardt D, et al. (2001) Microglia at brain stab wounds express connexin 43 and in vitro form functional gap junctions after treatment with interferon gamma and tumour necrosis factor alpha [J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA.98, 4190-4195.

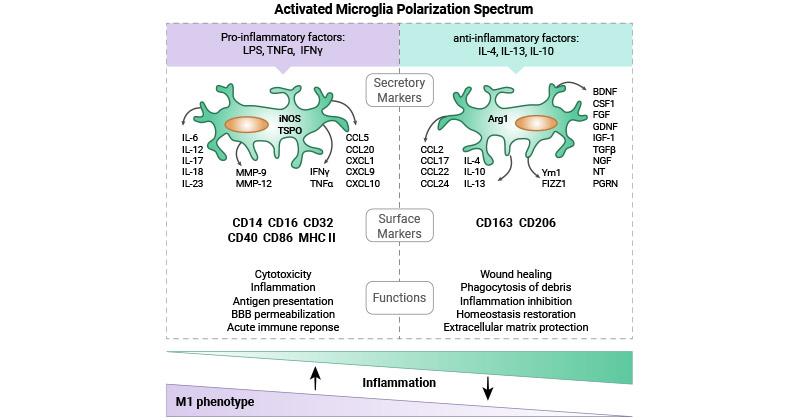

[9] Jurga AM, Paleczna M, Kuter KZ. Overview of General and Discriminating Markers of Differential Microglia Phenotypes [J]. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020 Aug 6;14:198.

[10] Wang J, He W, Zhang J. A richer and more diverse future for microglia phenotypes [J]. Heliyon. 2023 Mar 21;9(4):e14713.

[11] McGeer PL, McGeer EG (1995). The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases [J]. Brain Res. Rev.21, 195-218.

[12] McGeer PL, McGeer EG (1996). Anti-inflammatory drugs in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease.Ann.N. Y. Acad. Sci.777, 213-220.

[13] Barger SW, Harmon AD (1997).Microglial activation by Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein and modulation by apolipoprotein E [J]. Nature 388, 878-881.

[14] Diemel LT, Copelman CA, Cuzner ML (1998). Macrophages in CNS remyelination: friend or foe [J]? Neurochem.Res. 23, 341-347.

[15] Lees GJ (1993).The possible contribution of microglia and macrophages to delayed neuronal death after ischaemia [J]. J. Neurol.Sci. 114, 119-122.

[16] Tikka TM, Koistinaho JE (2001). Minocycline provides neuroprotection against N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglia [J]. J. Immunol. 166, 7527-7533.

[17] Yun S. P., Kam T.-I., et al. (2018). Block of A1 astrocyte conversion by microglia is neuroprotective in models of Parkinson’s disease [J]. Nat. Med. 24, 931–938.

[18] Fiala M, Liu QN, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-positive macrophages infiltrate the Alzheimer's disease brain and damage the blood-brain barrier [J]. Eur J Clin Invest 2002; 32: 360–371.

[19] Munder (2009). Arginase: An emerging key player in the mammalian immune system [J]. British Journal of Pharmacology, 158(3), 638-651.

[20] Fabriek et al. (2005). CD163-positive macrophages in inflammatory multiple sclerosis lesions: Distribution and impact on leukocyte recruitment [J]. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 164(1-2), 106-114.

Comments

Leave a Comment