Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTKs) is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that regulates cell growth, differentiation and migration. The Eph receptor family (erythropoietin-producing human hepatocellular carcinoma) is the largest RTKs family, which is highly conserved in structure and has many members [1].

EphA3(formerly known as HEK) is a member of Eph receptor family, and its abnormal changes are closely related to the occurrence and development of various tumors [2][3], which may cause changes in cell morphological characteristics and biological characteristics, such as cell growth and survival rate, cell adhesion, cell migration and anti-apoptotic ability.

1. Discovery of Eph Receptors

In 1987, Hirai et al. cloned EphA1, the first member of Eph gene family [4]. So far, in humans, Eph gene family has been found to have 14 members [5], which are widely distributed in normal tissues and tumor cells.

The EphA3 receptor was originally a surface antigen isolated from the pre-B lymphocytic leukemia cell surface (ALL) cell line (LK63) [6].

2. Eph Receptors

According to the homology, expression, distribution and binding properties of the Eph receptor family, they are divided into two subclasses: EphA (EphA1、EphA2、EphA3、EphA4、EphA5、EphA6、EphA7、EphA8、EphA10) and EphB (EphB1、EphB2、EphB3、EphB4、EphB6) receptors.

2.1 Eph Receptor Structure

The EphA3 gene is located in the 3p11.2 region of chromosome 3, which has mutations in many different tumor tissues.

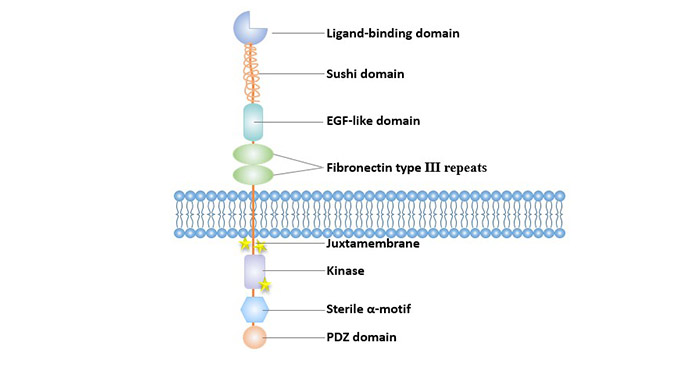

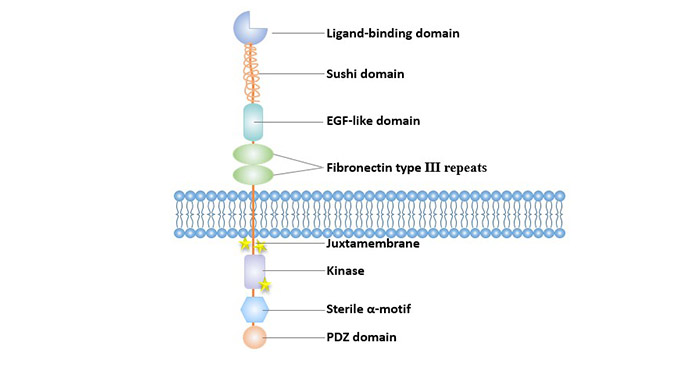

Eph receptor consists of three domains, extracellular ligand-binding region, intracellular functional region with tyrosine kinase activity, and transmembrane region composed of hydrophobic amino acids.

The extracellular domain includes an N-terminal globular domain (Glb), a cysteine-rich junction region consisting of a Sushi domain and an EGF-like domain and two fibronectin type III repeat regions. A globular domain is a key domain in which a ligand binds to a receptor, and determines the binding property of the receptor to the ligand. The mutation of the domain can destroy the ability of the anti-EphA3 monoclonal antibody to bind to the receptor.

The intracellular region includes a domain having tyrosine kinase activity, a sterile α-motif domain (SAM domain), and a PDZ domain [7]. The domain having tyrosine kinase activity in turn comprises a juxtamembrane region (where two tyrosine residues involved in Eph kinase activation are located) and the adjacent kinase region. The third tyrosine residue required for kinase activation is within the activation loop of the kinase domain.

SAM domain is highly conserved in Eph protein family, and tyrosine residues in SAM structure are necessary sites for aggregation of receptor signaling molecules [8]. SAM domain removal reduces the ability of EphA3 mutants to form dimers, and its phosphorylation level and kinase activity are affected [9].

Figure 1 Structure of Eph receptors

3. Ligands of EphA3

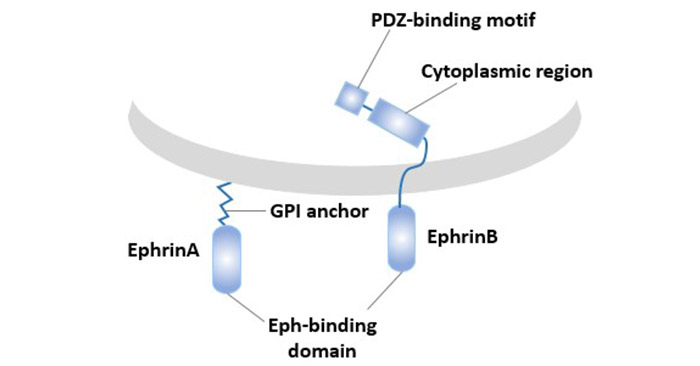

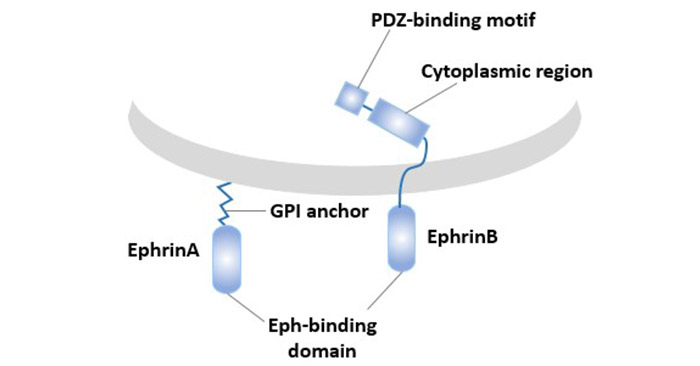

The ligands for EphA3: Ephrin-B2 and Ephrin-A5. The ligands can be divided into two subtypes, Ephrin-A and Ephrin-B, depending on how they are attached to the cell membrane. The Ephrin-A subtype is anchored to the cell membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol chain, a total of 5 kinds, and Ephrin-B ligands are 3 kinds, belonging to a single transmembrane protein, which is composed of intracellular structure and transmembrane.

The Eph family ligand is only active in the form of a membrane attachment, and the soluble form not only has no activity but actually acts as an antagonist.

Figure 2 Types and structures of Eph family ligands

4. Tissue Specificity of EphA3

EphA3 is highly expressed in various stages of embryonic development of the brain and spinal cord, lung, kidney, heart and muscle tissue [10]. In normal adult tissues, EphA3 is almost absent, and is sparsely expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) [11], relatively high in the retina, and low in the bladder, prostate, uterus and heart [12].

EphA3 is abnormally expressed in solid tumors such as gastric cancer, lung cancer, kidney cancer, colon cancer, melanoma, sarcoma, bile duct cancer [13], prostate cancer [14], and is associated with tumor invasion and metastasis [15]. In addition, EphA3 is overexpressed in some hematopoietic system tumors and lymphocyte tumors [16].

5. The Function of EphA3

Eph-ephrin mediated cellular communication controls the biological functions of cells, such as cell adhesion and de-adhesion, cell shape and movement.

The EphA3 receptor controls cell-cell adhesion and contractile responses. Regulation of cell-cell adhesion/de-adhesion is primarily regulated by proteolytic enzymes. Proteolysis disrupts EphA3-dependent cell-cell interactions. Transmembrane metalloproteinase ADAM10 was important to destroy the interactions between EphA/ ephrinA cells. The cysteine-rich domain of ADAM10 has a substrate binding pocket that specifically recognizes the EphA3/ephrin-A5 complex, localizes the protease domain, and separates ephrin from adjacent cell membranes.

Eph receptors and ligand play important roles in normal cell adhesion, migration, and angiogenesis. Studies show that Eph receptor or ephrin proteins play a role in maintaining the structure of blood vessels, kidneys, intestines and other tissues [17]. In addition, they are closely related to the formation of many tumor blood vessels and are thought to be involved in tumor invasion and metastasis.

5.1 EphA3 in Development

Eph-ephrin controls cell localization during normal and carcinogenic development by regulating cell-cell adhesion and de-adhesion, thereby affecting cell development. The Eph/ephrin signals are used in a variety of developmental processes, from gastrula embryogenesis and somatogenesis to vascular and neurological patterns.

Ephs is crucial to the embryological process, especially in the development of the nervous system. For example, EphA3 plays an important role in retinotectal development [18], which is consistent with the high expression of EphA3 in human retina.

5.2 EphA3 and Cancer

EphA3 is expressed in a variety of tumors and is associated with tumor stem cells and angiogenesis.

5.2.1 EphA3 in Solid Tumors

EphA3 is extensively mutated in cancer, with up to 40 mutations found in solid tumors [19]. Many mutations affect Ephrin binding domains, sushi-like and EGF-like domains (all involved in ligand binding) or kinase domains, and mutations in these domains may lead to abnormalities in positive signal transduction.

High EphA3 levels were found in melanoma. Activation of EphA3 on melanoma cells induces Rho-dependent cytoskeleton reorganization and cell retract, which may promote tumor metastasis.

Eph overexpression is widely found in stromal tumors, including sarcomas.

The expression of EphA3 was increased in osteosarcoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor as well as GBM and other neurotumors. High expression of EphA3 was also found in mesenchymal subtype of glioblastoma (GBM), in which the expression of EphA3 is closely related to the maintenance of stem cells.

EphA3 is also overexpressed in epithelial tumors, including lung and kidney tumors.

EphA3 is highly expressed in subgroups of breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer and gastric cancer.

Studies have shown that the mutation rate of EphA3 in lung cancer has reached 5%-10%, and the gene is absent in multiple groups of lung cancer tissues [20]. Overexpression of EphA3 can increase the apoptosis rate of tumor cells and G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest in small cell lung cancer, thereby reducing the resistance to chemotherapy drugs [21].

There are only a few cases of EphA3 expression and its role in liver cancer [22]. Studies have shown that the expression level of EphA3 in liver cancer is closely related to tumor size, tumor metastasis, grading and survival rate of liver cancer.

High expression of EphA3 in gastric cancer has also been confirmed, and high levels of EphA3 expression are associated with angiogenesis and poor prognosis in gastric cancer.

However, like other Ephs, the role and expression of EphA3 in cancer progression is not always consistent.

5.2.2 Hematological Malignancies

EphA3 is also abnormally expressed in hematological malignancies. EphA3 is structurally normal in hematological malignancies compared to solid tumors expressing EphA3.

Studies have shown that the expression of EphA3 is elevated in myeloproliferative tumors. In different periods, the expression levels were different. Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) had lower expression of EphA3 in the chronic phase and increased expression in the accelerated phase or embryonic stage.

In addition, Eph RTKs is involved in many other processes associated with malignant tumors, including changes in tumor microenvironment, which may promote the occurrence of malignant tumors and angiogenesis.

6. Eph/Ephrin Signaling

The Eph/Ephrin signaling pathway is outlined as follows: Ligand binding to the extracellular domain of the Eph receptor changes the conformation of the receptor, causing the receptor to migrate and aggregate on the membrane and form oligomerized receptor -ligand complex. The activation of Eph receptor tyrosine kinase leads to autophosphorylation and tyrosine phosphorylation of a large number of downstream intracellular substrate protein molecules, initiating different signaling pathways to transmit signals step by step.

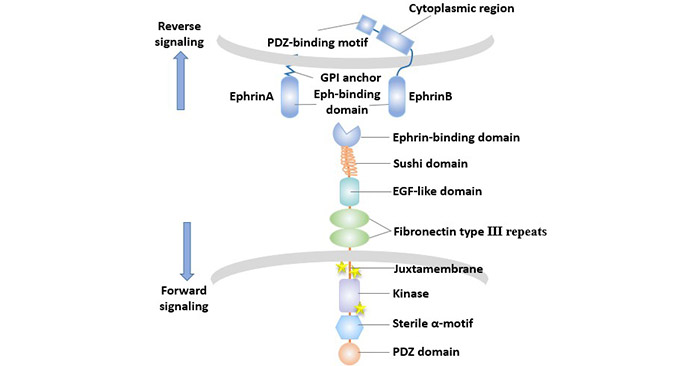

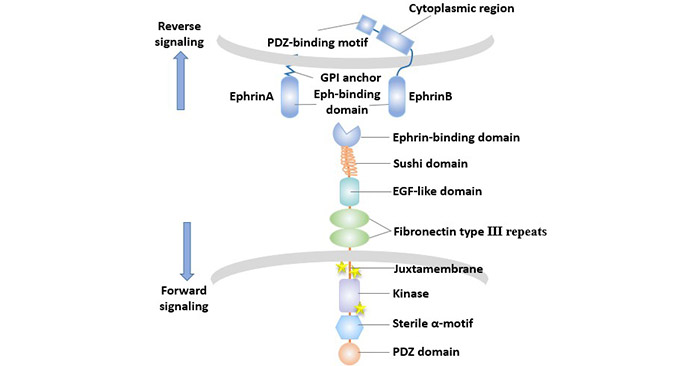

A striking feature of the Eph-ephrin interaction is the phenomenon of bidirectional signaling.

The characteristics of the Eph/Ephrin signaling pathway are that it acts not only on cells expressing Eph (forward signaling), but also on cells expressing Ephrin (reverse signal). Both positive and negative signals can be transmitted by tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent or non-dependent conduction pathways.

Figure 3 The bidirectional transmission of Eph/Ephrin signals

The formation of signal clusters (minimal tetramer) rather than receptor dimerization is a key requirement of Eph-ephrin signaling. Clustering of ephrin ligands is also necessary for Eph signaling. The membrane-bound or cluster ephrin stimulated Eph activity, while the soluble ephrins inhibited Eph activity. For example, ephrin-A5 could antagonize the activation of EphA3 [23].

Ephrin binding results in phosphorylation of the three major tyrosines (Y596 and Y602 in juxtamembrane domain and Y779 in the kinase activation loop), followed by activation of the kinase domain.

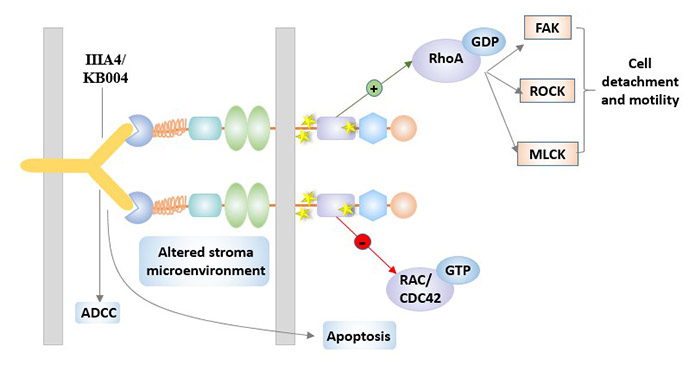

The CrkII adaptor protein is recruited to the activated kinase domain, which is critical for subsequent signaling cascades, resulting in activation of RhoA GTPases.

Eph RTKs target the cytoskeleton by altering the activation state of the Rho or Ras family GTPase to alter cell adhesion/rejection and cell motility [24].

Rho family GTPases act as downstream signaling molecules of the Eph receptor, and its activation shifts the balance within the Rho family to preferentially activate RhoA, inhibiting Rac1 and Cdc42. Rac1/cdc42 promotes cell movement and promotes the formation of plate foot and filamentous foot in migrating cells, while RhoA inhibits cell movement. This changes the motility of the cells.

Eph can not only mediate the change of cytoskeletal structure, but also promote or inhibit the survival pathway based on Eph RTK phosphorylation.

7. EphA3 Targeted Therapy

Eph receptor tyrosine kinases control cell-cell interactions during normal and oncogenic development and involve a range of processes including angiogenesis, stem cell maintenance and metastasis. Eph genes play a role in various mechanisms of tumor progression and, therefore, they can serve as targets for cancer therapy.

Given the role of EphA3 and other Ephs in tumors, considerable efforts have been made to develop Eph inhibitors, including the use of kinase inhibitors.

Vearing et al. [25] attempted to block EphA3 by using the high-adhesion ligand EphrinA5 of soluble EphA3, thereby inhibiting its function of promoting tumor growth.

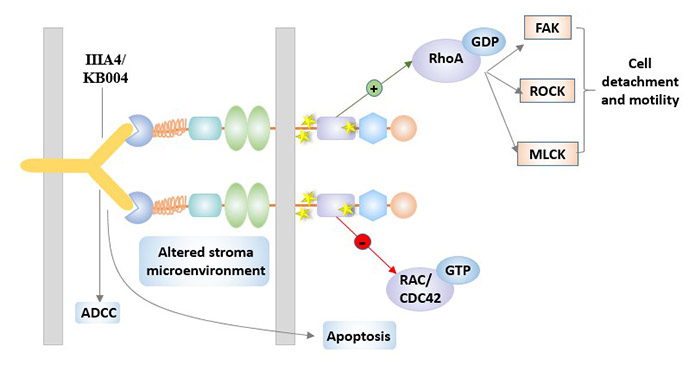

For EphA3, the primary therapeutic candidate is the monoclonal antibody IIIA4. IIIA4, an IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody targeting EphA3[6]. It has a high affinity for EphA3. The target of IIIA4 is located at the N-terminus of the extracellular domain of EphA3 adjacent to the ligand binding site. Similar to the ligand, pre-clustered IIIA4 effectively triggers EphA3 activation, cytoskeletal contraction and cell rounding.

IIIA4 was modified with antibody artificial engineering technology to prepare KB004. KB004 has a high affinity for EphA3 and a strong antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC). It may change the microenvironment, making it unfavorable for tumor growth and proliferation. KB004 is currently being evaluated in phase I/II ClinicalTrials in patients with hematologic malignancies (clinicaltrials. gov identifier: NCT01211691).

Figure 4 IIIA4 / KB004 in EphA3-targeted therapy

References

[1] Birgit M, Bettina R, Christin N, et al. Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands: Important Players in Angiogenesis and Tumor Angiogenesis [J]. Journal of Oncology, 2010, 2010: 1-12.

[2] Mélanie H, Schaffner F, Augustin H G. Eph receptor and ephrin ligand-mediated interactions during angiogenesis and tumor progression [J]. Experimental Cell Research, 2006, 312(5): 642-650.

[3] Xi H Q, Wu X S, Wei B, et al. Aberrant expression of EphA3 in gastric carcinoma: correlation with tumor angiogenesis and survival [J]. Journal of Gastroenterology, 2012, 47(7): 785-794.

[4] Hirai H, Maru Y, Hagiwara K, et al. A novel putative tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the eph gene [J]. Science, 1987, 238(4834): 1717-1720.

[5] Committee E N. Unified nomenclature for Eph family receptors and their ligands, the ephrins. Eph Nomenclature Committee [J]. Cell, 1997, 90(3): 403.

[6] Boyd A W, Ward L D, Wicks I P, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel receptor-type protein tyrosine kinase (hek) from a human pre-B cell line [J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1992, 267(5): 3262-3267.

[7] Pasquale, Elena B. Developmental Cell Biology: Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behavior [J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2005, 6(6): 462-475.

[8] Stein E, Lane A A, Cerretti D P, et al. Eph receptors discriminate specific ligand oligomers to determine alternative signaling complexes, attachment, and assembly?responses [J]. Genes & Development, 1998, 12(5): 667-78.

[9] Singh D R, Cao Q, King C, et al. Unliganded EphA3 dimerization promoted by the SAM domain [J]. Biochemical Journal, 2015, 471(1): 101-109.

[10] Kilpatrick T J, Brown A, Lai C, et al. Expression of theTyro4/Mek4/Cek4Gene Specifically Marks a Subset of Embryonic Motor Neurons and Their Muscle Targets [J]. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, 1996, 7(1): 62-74.

[11] Hafner C, Schmitz G, Meyer S, et al. Differential Gene Expression of Eph Receptors and Ephrins in Benign Human Tissues and Cancers [J]. Clinical Chemistry, 2004, 50(3): 490-499.

[12] Chiari R, Gérald Hames, Stroobant V, et al. Identification of a Tumor-specific Shared Antigen Derived From an Eph Receptor and Presented to CD4 T Cells on HLA Class II Molecules [J]. Cancer Research, 2000, 60(17): 4855-63.

[13] Suksawat M, Techasen A, Namwat N, et al. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and its upstream regulators in Opisthorchis viverrini associated cholangiocarcinoma and its clinical significance [J]. Parasitology International, 2016: S1383576916300976.

[14] Hood G, Laufer-Amorim R, Fonseca-Alves C E, et al. Overexpression of Ephrin A3 Receptor in Canine Prostatic Carcinoma [J]. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 2016: S0021997516000037.

[15] Xi H Q, Zhao P. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of EphA3 and CD133 expression in colorectal carcinoma [J]. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 2011, 64(6): 498-503.

[16] Wicks I P, Wilkinson D, Boyd E S W. Molecular Cloning of HEK, the Gene Encoding a Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Expressed by Human Lymphoid Tumor Cell Lines [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1992, 89(5): 1611-1615.

[17] Ogawa K. EphB2 and ephrin-B1 expressed in the adult kidney regulate the cytoarchitecture of medullary tubule cells through Rho family GTPases [J]. Journal of Cell Science, 2006, 119(3): 559-570.

[18] Feldheim D A. Loss-of-Function Analysis of EphA Receptors in Retinotectal Mapping [J]. Journal of Neuroscience, 2004, 24(10): 2542-2550.

[19] Lisabeth E M, Fernandez C, Pasquale E B. Cancer Somatic Mutations Disrupt Functions of the EphA3 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase through Multiple Mechanisms [J]. Biochemistry, 2012, 51(7): 1464-1475.

[20] Zhuang G, Song W, Amato K, et al. Effects of Cancer-Associated EphA3 Mutations on Lung Cancer [J]. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2012, 104(15): 1183-1198.

[21] Peng J, Wang Q, Liu H, et al. EphA3 regulates the multidrug resistance of small cell lung cancer via the PI3K/BMX/STAT3 signaling pathway [J]. Tumor Biology, 2016, 37(9): 11959-11971.

[22] Tao Kai-Shan. High levels of EphA3 expression are associated with high invasive capacity and poor overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Oncology Reports, 2013, 30(5).

[23] Lawrenson I D, Wimmerkleikamp S H, Lock P, et al. Ephrin-A5 induces rounding, blebbing and de-adhesion of EphA3-expressing 293T and melanoma cells by CrkII and Rho-mediated signaling [J]. Journal of Cell Science, 2002, 115(Pt 5): 1059.

[24] Pasquale E B. Eph-Ephrin Bidirectional Signaling in Physiology and Disease [J]. Cell, 2008, 133(1): 0-52.

[25] Vearing C. Concurrent Binding of Anti-EphA3 Antibody and Ephrin-A5 Amplifies EphA3 Signaling and Downstream Responses: Potential as EphA3-Specific Tumor-Targeting Reagents [J]. Cancer Research, 2005, 65(15): 6745-6754.

CUSABIO team. EphA3-A Regulator of Cell Adhesion and Migration. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20959.html

Comments

Leave a Comment