March 18th of each year is "National Liver Love Day." Liver cancer presents an ongoing global health challenge, with its incidence on the rise across the world. When it comes to liver cancer, we have to mention hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which accounts for over 90% of all liver cancer cases. It is anticipated that, by the year 2025, over 1 million people will be diagnosed with HCC annually [1].

1. What Is Hepatocellular Carcinoma?

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), also known as hepatoma, is the most common form of primary liver cancer with high mortality and low 5-year survival rates. HCC ranks as the sixth most prevalent cancer globally and stands as the third primary cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [2]. HCC morbidity has risen recently, with an annual incidence of 630,000 new cases in males and 273,000 new cases in females [2].

HCC demonstrates a higher prevalence in males, with the incidence of the disease being around 2 to 4 times higher in males than in females, predominantly occurring in the population aged 50 to 70 years [3,4]. HCC originates from hepatocytes and develops in the context of fibrosis or cirrhosis in more than 90% of cases. Due to limited effective treatments and early detection methods, HCC is generally diagnosed at an advanced stage.

2. The Etiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

HCC usually develops as a result of hepatic lesions caused by different etiologies, which gradually progress to fibrosis and eventually cirrhosis. Although rare, HCC can also occur in individuals without cirrhosis. In cirrhotic livers, HCC marks the culmination of a progressive hepatic carcinogenesis sequence, starting with regenerative nodules, progressing through dysplastic nodules, and ultimately evolving into HCC.

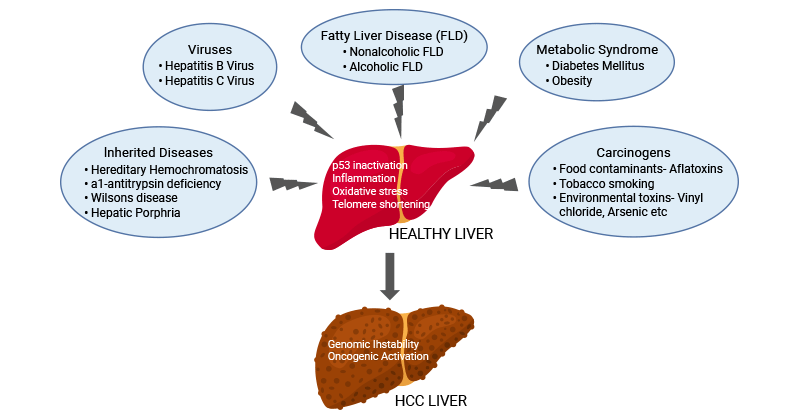

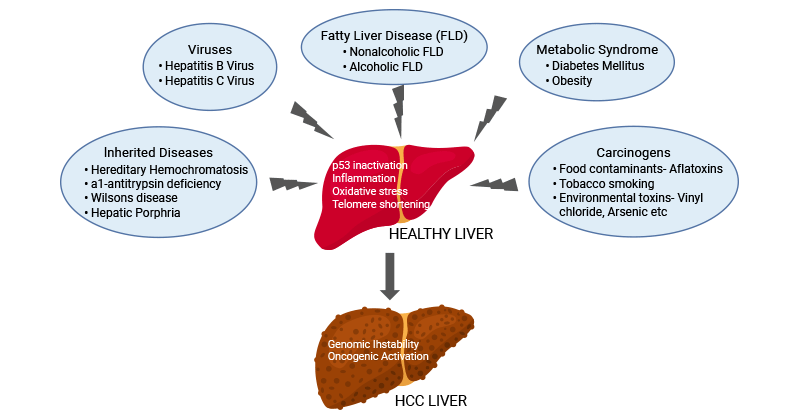

The major risk factors for HCC include viral infection resulting from hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV, alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and metabolic syndromes such as diabetes and obesity.

Other contributing factors that are recognized for raising the incidence of HCC encompass carcinogens (e.g. tobacco smoking, food contaminants like aflatoxins, and various environmental toxins like vinyl chloride and arsenic) and inherited diseases such as hereditary hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, hepatic porphyria, and Wilsons disease [5,6].

Figure 1. The etiology of HCC

This picture is cited from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7734960/

2.1 Hepatitis Viral Infection

Chronic infections by HBV and HCV are the major risk factors for HCC development. The hepatitis virus-related mechanisms driving the development of HCC are intricate and lead to liver cirrhosis, progressing to HCC in approximately 80-90% of cases [7,8].

The annual incidence of HCC in individuals with cirrhosis related to HBV is approximately 2.3% [9]. The recurrent integration of HBV's genetic material into the human genome results in p53 activation, inflammation, or oxidative stress, contributing to the promotion of hepatocarcinogenesis [10,11]. Higher levels of HBV DNA and HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), positivity for HBeAg, HBV genotype C, as well as basal core-promoter mutations, are important factors associated with a higher risk for the development of HCC [12].

Different from HBV, HCV is an RNA virus and does not integrate its genetic material into the host genome during infection. HCV structural and non-structural proteins exert a prominent role in hepatocarcinogenesis. The hepatocarcinogenesis induced by HCV is a complex process that activates multiple cellular pathways commencing with the initiation of HCV infection, leading to persistent hepatic inflammation, which subsequently advances to the development of liver cirrhosis and eventual HCC [13].

HCV proteins regulate various host cellular processes, including transcriptional modulation, cytokine regulation, hepatocyte growth regulation, and lipid metabolism that cause chronic liver injury. They also induce oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and lead to epigenetic changes by manipulating miRNA and lncRNA in host cells [14].

2.2 AFLD and NAFLD

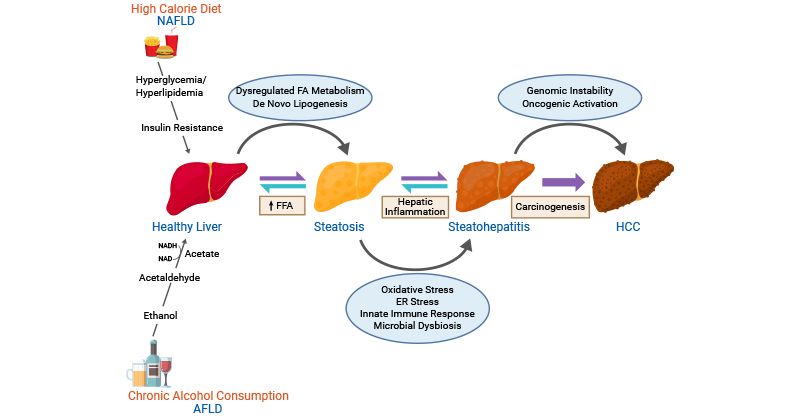

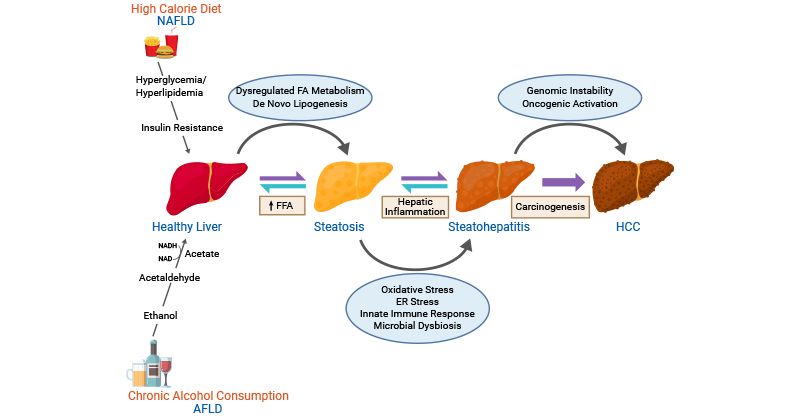

Heavy alcohol consumption, or alcohol abuse, the main cause of AFLD, causes liver damage through the accumulation of fats, inflammation, scarring, and cirrhosis, resulting in HCC. Excessive alcohol intake increases the associated risk of HCC in a dose-dependent manner [15]. Studies have indicated that individuals with HBV or HCV infection who consume alcohol heavily have an increased risk of HCC compared to their non-alcohol-consuming counterparts.

NAFLD is a condition characterized by the accumulation of hepatic lipids due to high caloric intake and insufficient physical activity. Upon inflammatory insults, NAFLD progresses to its severe form nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is coupled with insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, adipose tissue remodeling, oxidative damage, genetic factors, and epigenetic alterations, stimulates oncogenic signaling, fostering the development of HCC. NAFLD is often linked to metabolic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Figure2. Molecular mechanisms involved in AFLD- and NAFLD-associated HCC

This picture is cited from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7734960/

2.3 Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity contributing to the onset and progression of HCC is mainly attributed to NAFLD and insulin resistance (IR) [16,17]. Excessive hepatic lipid accumulation can cause adipokine imbalance, leading to chronic inflammation. This inflammation stimulates local or systemic insulin resistance (IR), elevating insulin and IGF-1 levels and promoting abnormal hepatocyte proliferation. Obesity is one of the comorbidities of NAFLD, which may advance into nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), hepatic fibrosis, or even hepatic cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a well-established risk factor for HCC, irrespective of its etiology.

Obesity also promotes HCC progression by regulating metabolites, immunity, and autophagy in the tumor microenvironment.

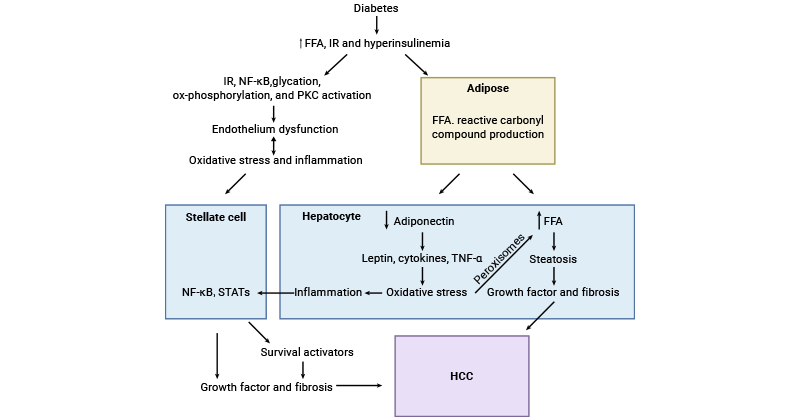

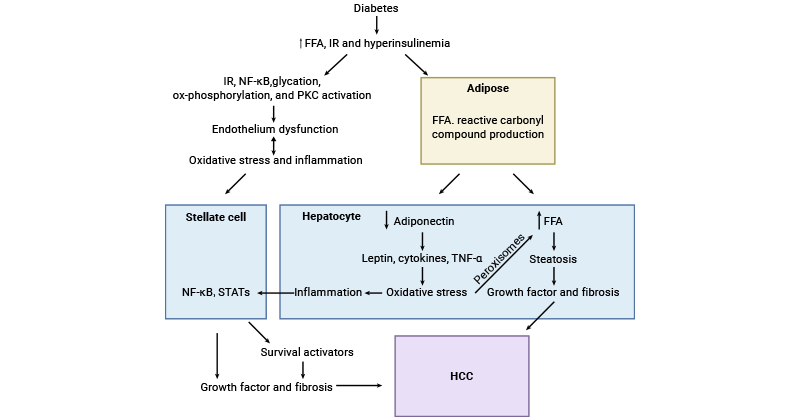

Diabetes triggers increased free fatty acid (FFA) generation, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance (IR), culminating in heightened levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammation, and oxidative stress within adipocytes and hepatocytes [18]. The compromised activity of PKC, NF-κB, STAT, leptin, and TNF-α cascades accelerates fibrosis through stellate cells, thereby contributing to the progression of HCC.

Figure 3. Brief illustration of HCC development in diabetes

This picture is cited from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9840929/

2.4 Carcinogens

Apart from viral factors, chemical carcinogens like aflatoxins, tobacco smoking, vinyl chloride, arsenic, and others also play an important role in the development of HCC.

The fungal toxin aflatoxin B1 triggers mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene, promoting uncontrolled proliferation of hepatocytes and ultimately resulting in the development of HCC. Tobacco smoking produces chemicals 4-aminobiphenyl and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can cause hepatotoxicity. Exposure to vinyl chloride, arsenic, and toluene has been demonstrated to increase the risk of HCC because such kind of chemicals exert hepatocarcinogenic effects by inducing oxidative stress and telomere shortening.

2.5 Other less prevalent Risk Factors

Certain metabolic disorders such as hereditary hemochromatosis, which is linked to heightened hepatocyte- and hepatocellular damage-mediated iron absorption; and α1-antitrypsin deficiency, which entails an increased presence of antitrypsin polymers in hepatocytes, leading to hepatocyte death and cirrhosis.

The mechanisms by which these etiological factors may induce hepatocarcinogenesis mainly include p53 inactivation, inflammation, oxidative stress, and telomere shortening leading to genomic instability and activation of multiple oncogenic signaling pathways.

3. Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in the Molecular Pathogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

During the progression of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis, which are the foundations for the majority of HCC cases, liver cells gradually amass a multitude of genetic mutations and epigenetic changes.

3.1 Gene Mutations

Some oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes are identified to be recurrently mutated in HCC through high throughput next-generation sequencing. The most prevalent driver gene changes, occurring in approximately 80% of HCC cases, are TERT promoter mutations, viral insertions, chromosome translocation or gene amplification mediated telomerase activation [19]. Research has shown the activation of the Wnt–β-catenin signaling pathway in 30–50% of cases, is attributed to mutations in CTNNB1 or the inactivation of AXIN1 or APC.

Additional frequent gene mutations are found in TP53, RB1, CCNA2, CCNE1, PTEN, ARID1A, ARID2, RPS6KA3 or NFE2L2, involving in disrupting cell cycle control. Recurrent focal chromosome amplification-causing overexpression of genes, including CCND1, FGF19, VEGFA, MYC, or MET, activates diverse oncogenic signaling pathways.

3.2 Epigenetic Modifications

Aberrant epigenetic modifications in HCC include DNA methylation, histone modifications (acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, etc.), non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), and the presence of abnormal histone variants. Viral hepatitis infections, particularly hepatitis B and C, further influence HCC epigenetics.

4. Signaling Pathways Involved in the Carcinogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Although the mechanisms vary due to underlying causes, they are typically developed as the sequence: liver injury → chronic inflammation → fibrosis → cirrhosis → hepatocellular carcinoma.

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are released from damaged or necrotic hepatocytes, activating pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and causing an inflammatory response. Unresolved chronic inflammation leads to fibrosis and further results in cirrhosis, which eventually develops HCC. The majority of HCC cases (80-90%) having a history of cirrhotic events.

Dysregulation of several signaling pathways in HCC, including Wnt/B-catenin, TGF-β, EGF, SHH, Notch, VEGF, HGF, JAK/STAT, Hippo, and HIF, results in uncontrolled cell proliferation, prolonged cell viability, metastasis, and recurrence of liver carcinoma cells [20].

4.1 Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

In liver tumors, HCC cells, and macrophages serve as Wnt ligands. Environmental risk factors induce mutations in Wnt pathway components, resulting in HCC's Wnt signaling overactivation. Wnt ligand binding to Frizzled (Fzd) and LRP receptors phosphorylates and activates Disheveled, inhibiting the degradation of GSK3β, Axin, and APC, and releasing β-catenin. Activated β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, binds co-activators (LEF/TCF or CBP/p300), activating target genes involved in CSC maintenance (CD44, EpCAM), proliferation (cyclin D1, c-Myc), and EMT.

LGR5, a receptor associated with the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, is implicated in the metastasis of HCC. Additionally, Wnt/β-catenin plays a role in regulating angiogenesis within the liver tumor.

4.2 TGF-β Signaling

In the liver tumor, TGF-β is mainly generated by stromal cells- or hepatocytes-derived cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF). TGF-β binds to the TβRII/TβRI receptor, phosphorylating and activating Smad2/3 and promoting their nuclear translocation with Smad4. TGF-β-mediated upregulation of Snail and downregulation of E-cadherin induces EMT and metastasis of polarized hepatocytes. The TGF-β signaling also preserves the CSC subpopulation, enhances HCC proliferation, induces VEGF expression, and recruits endothelial cells.

In collaboration with EGF, Wnt, and SHH pathways, the TGF-β signaling promotes mesenchymal traits in HCC cells. TGF-β also boosts the conversion of tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) to M2-like macrophages, facilitating HCC proliferation, metastasis, and neoangiogenesis of HCC, while suppressing MHC-I/II expression and modulating immune cell defense in HCC.

4.3 Epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling

Abnormal activation of the EGF pathway in HCC can occur through autocrine or paracrine secretion, stimulating cell proliferation and migration. EGFRs are usually over-expressed and over-activated in HCC. EGF binding to EGFR activates PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK, P38/MAPK, or NF-kβ proteins through downstream signal transduction. The EGF signaling plays a role in recruiting inflammatory cells for the secretion of interleukins such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, and tumor progression.

4.4 Hedgehog (Hh) signaling

After liver injury, hepatocytes and Kupffer cells secrete SHH ligands. SHH binds to the Patched (Ptch) receptor and evokes the Smoothened (Smo) receptor, initiating the signaling cascade and leading to nuclear translocation of the transcription factor and glioma protein (Gli). In HCC, SHH induces the expression of genes associated with the cell cycle (cyclin D, c-Myc) and invasion (especially MMPs), and specific to cancer stem cells (CSC) like CD133. Gli increases the expression of VEGF in HCC and tumor angiogenesis. SHH can also cooperate with the TGF-β, Wnt, or Notch pathways to facilitate EMT and metastasis in HCC.

4.5 Notch signaling

The Notch receptor on hepatocytes interacting with the ligand on the macrophages activates the Notch pathway. The intracellular domain (NICD) of the Notch receptor undergoes cleavage by γ-secretase, subsequently translocating to the nucleus and binding to DNA-binding transcription factors, including Hes1, P53, cyclin-D, and c-Myc, which are related to cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis markers. The Notch pathway crosstalk with other pathways triggering different effects, such as with PI3K and mTOR pathways for HCC proliferation, with Wnt and SHH pathways for CSC maintenance, and with the VEGF pathway for angiogenesis.

4.6 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling

The hepatic tumor cells generate growth factors that stimulate angiogenesis to guarantee a proficient supply of nutrients and oxygen within solid tumors. Angiogenic signals can be initiated through various pathways, including HGF, PDGF, FGF, and VEGF. VEGF, as the predominant angiogenic factor, not only triggers angiogenesis but also participates in autocrine interactions with RTK, activating the PI3K/Akt pathway in HCC.

4.7 Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) signaling

HGF was identified as a regulator of HCC proliferation, survival, and metastasis. HGF interacts with the c-met receptor and activates various downstream signaling pathways, including the PI3K, ERK, and Jnk/Stat3 pathways, stimulating HCC cell proliferation, inducing angiogenesis, enhancing the invasion and metastasis of HCC cells, and contributing to the resistance of HCC cells to cell death.

4.8 Janus kinases (JAK)/STAT3 signaling

The JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway plays a critical role in the development and pathogenesis of HCC. Chronic inflammation, a hallmark of liver diseases, triggers the activation of JAK/STAT3 signaling, which promotes the survival and proliferation of damaged hepatocytes, contributing to HCC initiation and progression. Various cytokines and growth factors, including IL-6 and HGF, stimulate JAK/STAT3 signaling.

Once activated, STAT3 translocates to the nucleus, acting as a transcription factor and promoting genes involved in cell proliferation, survival, and anti-apoptotic pathways. Additionally, STAT3 activation is associated with angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune modulation in HCC.

4.9 Hippo signaling

Activation of the Hippo signaling pathway inhibits the YAP/TAZ/TEAD transcriptional activity, suppressing the pro-tumorigenic processes, including proliferation, metastasis, and inhibition of apoptosis and autophagy. Hippo signaling plays a crucial role in liver development and regeneration, maintaining liver homeostasis. In HCC, dysregulation of the Hippo pathway, often due to genetic mutations or altered expression, leads to YAP and TAZ activation. This nuclear localization results in the upregulation of genes promoting cell proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and angiogenesis in HCC cells.

Additionally, Hippo signaling influences the tumor microenvironment, with YAP activation contributing to factors that foster inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis, creating a supportive niche for HCC progression.

5. Biological Markers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Biological markers play a pivotal role in the detection, diagnosis, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma by facilitating early identification, risk stratification, and ongoing monitoring of the disease. Here are some biomarkers found in blood, urine, or other fluids that serve as a sign of HCC.

| HCC Markers |

Effects |

| Embryonic antigens |

AFP |

Highly expressed; sensitivity: 20-60%, specificity: >80% |

| AFPL1 |

Early in the course of hepatic illness, AFPL1 levels rise |

| AFPL2 |

Early in the course of hepatic illness, AFPL2 has a more moderate affinity for lectin |

| AFPL3 |

Only produced by HCC cells, exclusively elevated in HCC patients; for the early identification of HCC |

| Protein antigens |

DKK-1 |

In combination with AFP for the diagnosis of HCC, especially in those cases with low AFP concentration |

| GP73 |

Not expressed in healthy hepatocytes; combining GP73, DKK-1, and AFP increased the sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of HCC |

| ANXA2 |

Overexpression is involved in the growth and metastasis of HCC; has higher sensitivity and specificity than AFP |

| HSP70 |

A viable and sensitive marker to distinguish early HCC from precancerous lesions |

| EMA (epithelial membrane antigen) |

EMA expression can help diagnose liver cancer |

| Fibronectin |

Aberrant fibronectin expression promotes HCC development |

| Nuclear matrix proteins (NMPs) |

A biomarker of organ injury in liver illnesses |

| Cytokeratins (CKs) |

Any cellular injury impairing the hepatic integrity may cause CKs to release into the bloodstream |

| AGP (α-1-acid glycoprotein) |

Aberrant glycosylation of AGP is highly associated with the carcinoma progression of HCC, especially with elevated fucosylation |

| GPC3 (Glypican-3) |

Not expressed in adult livers, using GPC3 and AFP together provides significant sensitivity and specificity |

| NGAL (Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin) |

Patients with chronic liver disease would benefit from using urinary NGAL to diagnose HCC |

| OPN (Osteopontin) |

Elevated in HCC patients; more specific but less sensitive than AFP |

| SCCA (squamous cellular carcinoma antigen) |

Expressed by neoplastic cells of epithelial origin and detected in HCC tissues; increased AFP’s capacity to diagnose HCC by up to 90% |

| Enzymes and Isoenzymes |

DCP (Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin) |

In malignant hepatocytes, carboxylate glutamic acid is converted into DCP; combining DCP and AFP can increase the sensitivity of HC detection |

| GGT (Gamma-glutamyl transferase) |

Combination of GGT and AFP showed a higher sensitivity and lower specificity compared to using AFP alone |

| MMP1 |

Low level expression in viral hepatitis and HCC |

| MMP2 |

High level of expression during viral hepatitis and HCC |

| MMP3 |

| MMP7 |

| MMP8 |

High level of expression during HCC and cirrhosis |

| MMP9 |

| MMP10 |

| MMP12 |

| MMP13 |

| MMP14 |

| MMP15 |

Low level of expression during liver regeneration |

| MMP16 |

High level of expression during viral hepatitis, HCC, and cirrhosis |

| MMP24 |

High level expression during liver regeneration |

| Glutamine synthetase (GS) |

Elevated GS mRNA expression has been related to metastasis and cancer progression in HCC |

| Alpha L fucosidase (AFU) |

Its measurement as a part of routine liver function tests contributes to the overall assessment of liver health and assists clinicians in diagnosing and monitoring liver pathologies |

| Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) |

Decreased significantly in the serum of HCC patients |

| Growth Factors and Their Receptors |

TGFβ |

Hepatocarcinogenesis is linked to the increased cellular expression of TGFβ-1 |

| IGF-1 |

HCC patients have significantly three times lower blood concentrations of IGF-1 than IGF-2 compared with the levels in patients without HCC |

| VEGF |

The expression of VEGF is upregulated in HCC patients’ tissues |

| HGF (Hepatocyte growth factor) |

Compared to the control group with chronic hepatitis, the HCC group exhibits significantly elevated levels of HGF. |

| Cytokines |

IL-6 |

High levels have been detected in HCC patients |

| IL-8 |

The Table information is cited from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10377276/

6. Current Research and Challenges of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Despite the utilization of surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiotherapy, and chemotherapy as potentially curative treatments for HCC, the prognosis remains unfavorable for patients with advanced disease.

The intrinsic chemoresistance of HCC has long limited the availability of effective treatments. In addition to the deprive of therapeutic options, the presence and severity of the underlying liver disease, the accompanying trait of nearly all HCC cases, exacerbates patients’ diagnosis and calls for a meticulous balance between the benefits of treatment and the risk of hepatic decompensation.

In 2022, substantial advancements were achieved in all facets of liver cancer research, with a notable focus on immunotherapy-based therapies emerging as the primary treatment choice for primary liver cancers, including HCC. The primary focus of immunotherapy research is on immune checkpoint inhibitors, which have been widely utilized in the treatment of HCC.

References

[1] Llovet JM, Kelley RK, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma [J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers (2021) 7(1):6.

[2] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [J]. CA. 2021;71(3):209–249.

[3] Wands J. Hepatocellular carcinoma and sex [J]. N Engl J Med (2007) 357:1974–6.

[4] Mittal S, Kramer JR, et al. Role of Age and Race in the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Veterans With Hepatitis B Virus Infection [J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol (2018) 16:252–59.

[5] Yang JD, Hainaut P, et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management [J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 16:589–604.

[6] Jindal A, Thadi A, Shailubhai K. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Etiology and Current and Future Drugs [J]. J Clin Exp Hepatol (2019) 2:221–32.

[7] Kanda T, Goto T, et al. Molecular Mechanisms Driving Progression of Liver Cirrhosis towards Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B and C Infections: A Review [J]. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20:1358.

[8] Yang JD, Kim WR, et al. Cirrhosis is present in most patients with hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol (2011) 9:64–70.

[9] Takano, S.; Yokosuka, O.; et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B and C: A prospective study of 251 patients [J]. Hepatology 1995, 21, 650–655.

[10] Jiang Z, Jhunjhunwala S, et al. The effects of hepatitis B virus integration into the genomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients [J]. Genome Res (2012) 22:593–601.

[11] Jia L, Gao Y, He Y, Hooper JD, Yang P. HBV induced hepatocellular carcinoma and related potential immunotherapy [J]. Pharmacol Res (2020) 159:104992.

[12] Sumi, H.; Yokosuka, O.; et al. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the progression of chronic type B liver disease [J]. Hepatology 2003, 37, 19–26.

[13] Goossens N, Hoshida Y. Hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Clin Mol Hepatol (2015) 21:105–14.

[14] Irshad M, Gupta P, Irshad K. Molecular basis of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by hepatitis C virus infection [J]. World J Hepatol (2017) 9:1305–14.

[15] Roerecke M, Vafaei A, Hasan OSM, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019; 114: 1574–1586.

[16] Wu J, Zhu AX. Targeting insulin-like growth factor axis in hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. J Hematol Oncol (2011) 4:30.

[17] Yang, J., He, J., Feng, Y., & Xiang, M. (2023). Obesity contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development via immunosuppressive microenvironment remodeling [J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 14.

[18] Singh MK, Das BK, et al. Diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a pathophysiological link and pharmacological management [J]. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;106:991-1002.

[19] Guichard, C. et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Nat. Genet. 44, 694–698 (2012).

[20] Farzaneh, Z., Vosough, M., Agarwal, T., & Farzaneh, M. (2021). Critical signaling pathways governing hepatocellular carcinoma behavior; small molecule-based approaches [J]. Cancer Cell International, 21.

CUSABIO team. What Essential Biological Knowledge is Needed for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Research?. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20808.html

Comments

Leave a Comment