Programmed death-1 (PD-1), also known as CD279, is another important negative costimulatory molecule following the discovery of CTLA4. Its ligand is PD-L1, also known as CD274, which, like PD-1, belongs to the CD28/B7 family.

PD-1 binds to its ligand and transmits a negative costimulatory signal, inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation, and plays a key role in regulating T cell activation and immune tolerance.

1. Structure of PD-1

PD-1 was discovered in 1992 [1] and is a member of the B7-CD28 family.

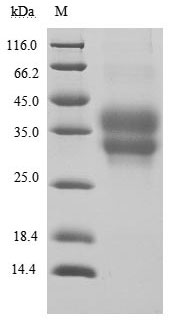

The PD-1 gene is located on human chromosome 2q37 and encodes a type I transmembrane glycoprotein with a relative molecular mass of 50 kDa-55 kDa. The protein is expressed in monomeric form on the cell membrane surface.

The PD-1 protein consists of an extracellular region, a transmembrane region, and an intracellular region.

The extracellular domain contains an immunoglobulin variable domain.

Cytoplasmic region: PD-1 intracellular region contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM). These two motifs each contain one tyrosine.

When PD-1 binds to its ligand, both tyrosines are phosphorylated, but ITIM does not transduce the inhibitory signal of the PD-1 signaling pathway, and only the phosphorylation of tyrosine in ITSM can play a regulatory role.

2. The Expression of PD-1

PD-1 is mainly expressed in activated CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, activated B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, natural killer T cells, dendritic cells (DC) and activated monocytes, and is closely related to their differentiation and apoptosis.

The expression of PD-1 can be induced by TCR or B cell receptors, and tumor necrosis factor can enhance the expression of PD-1.

Extensive expression of PD-1 suggests that it has an essential role in maintaining a negative immune response in the body.

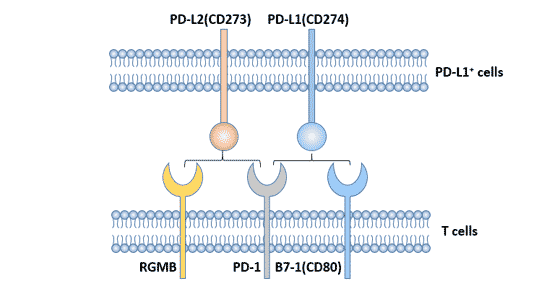

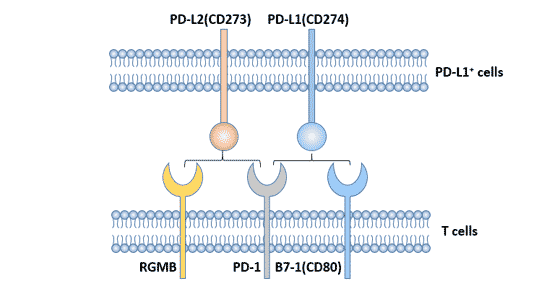

3. Ligands of PD-1

The ligands of PD-1 are mainly PD-L1 and PD-L2, and PD-L1 is the main ligand [2], which is highly expressed in various malignant tumors.

Figure 1. Ligands of PD-1

3.1 PD - L1

3.1.1 The Structure of PD - L1

PD-L1 (B7-H1, CD274) is a ligand for PD-1, which is located on human chromosome 9p24. It was discovered in 1999 by Dong et al [3] and is a new member of the B7 family.

PD-L1 is a 40 kDa type I transmembrane glycoprotein composed of an extracellular domain, a hydrophobic transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic domain.

The extracellular domain has an immunoglobulin constant region (IgC) domain and an immunoglobulin variable region (IgV) domain. Although the PD-L1 molecular extracellular amino acid sequence has only 20% and 15% homology with B7-1 and B7-2, their secondary structure and tertiary structure are very similar, and thus exhibit similar biological functions.

The PD-L1 cytoplasmic domain contains a protein kinase C phosphorylation site, but the signal transduction motif in the intracellular region is currently unclear.

3.1.2 The Expression of PD-L1

CD274 is highly expressed in the heart, skeletal muscle, placenta, and lung, and is weakly expressed in the thymus, spleen, kidney, and liver. PD-LI is expressed on T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and cultured bone marrow-derived mast cells, and the expression was significantly up-regulated in activated cells.

In the non-hematopoietic system, PD-L1 is expressed in vascular endothelial cells, epithelial cells, fibroblast reticulocytes, islet cells, skeletal muscle cells, embryonic trophoblast cells, astrocytes, hepatocytes, placenta, retinal pigment epithelial cells, etc.

PD-L1 is expressed in a variety of tumor cells, such as human lung cancer, ovarian cancer, colon cancer, kidney cancer, and melanoma.

3.2 PD-L2

PD-L2 was identified by Freeman laboratory [4]. Human PD-L2 (B7-H2, CD273) gene is also located in chromosome 9p24, encoding 247 amino acids of type I transmembrane protein. The homology of PD-L1 and PD-L2 is 40%. The affinity between PD-L2 and PD-1 is 2-6 times that of PD-L1.

Compared with PD-L1, the expression of PD-L2 is relatively limited, and PD-L2 is inductively expressed on the surface of dendritic cells, macrophages, bone marrow-derived mast cells and other cells [5] [6]. Human PD-L2 is also expressed in vascular endothelial cells.

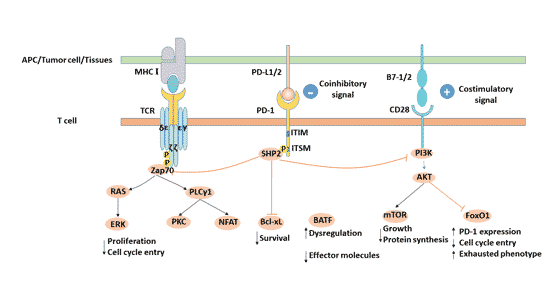

4. PD-L1/PD-1 Signaling Pathway

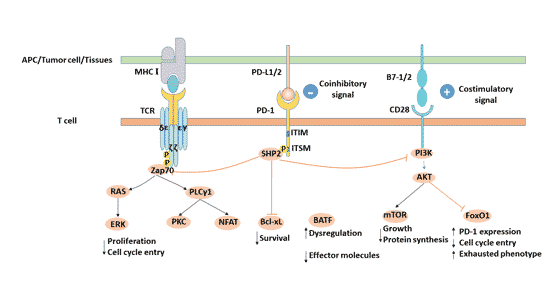

After PD-1 binds to its ligand PD-L1, tyrosine in the ITSM domain of PD-1 cytoplasmic region is phosphorylated, and SHP2 phosphatase molecules are recruited to cell membrane [7], and further inhibition of PI3K/PKB mediated Zap-70/CD3 zeta and PKC theta phosphorylation, inhibiting T cell proliferation, differentiation and cytokine production [8] [9].

Figure 2. PD-L1/PD-1 signaling pathway

4.1 Function of PD-1 / PD-L1 Signal Pathway

IFN-γ up-regulates PD-L1 on the surface of normal tissue cells and different tumor tissues, and down-regulates the immune response of the tumor microenvironment by inducing PD-L1 expression.

After T cells are stimulated by inflammatory signals, PD-1 is induced to produce and limit the function of T cells in a variety of peripheral tissues dominated by infections and tumors, thereby limiting the amplification and duration of the immune response, thereby avoiding damage to normal tissue.

Although the physiological functions of PD-L1 and PD-1 are up-regulated to avoid the expansion of inflammation and reduce tissue damage, the induced production of PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment will promote the apoptosis of activated T cells and stimulate the production of IL-10 in human peripheral blood T cells to regulate the immunosuppression.

The interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 plays an important role in inhibiting T cells in vivo. PD-L1 binds to receptor PD-1 on T cell membrane to produce an inhibitory signal, which can prevent proliferation and activation of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, down-regulate the expression of some anti-apoptotic molecules and pro-inflammatory factors, and change the tumor microenvironment.

This weakens the ability of the body to monitor and clear tumor cells, resulting in immune escape, allowing tumor cells to proliferate indefinitely in the body [10]. Therefore, blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway restores the killing effect of the immune system on tumor cells.

4.2 PD-1/PD-L1 Signaling Pathway and Diseases

PD-1 binds with its main ligand PD-L1 to form the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway, which plays an important role in maintaining peripheral tolerance and regulating antigen-specific T cell activity, and is an important factor influencing chronic infectious diseases and autoimmune diseases.

The PD-1/PD-L pathway has a positive regulatory effect on autoimmune diseases and transplant rejection, but plays a negative role in antiviral and antitumor effects.

4.2.1 PD-1/PD-L1 Signaling Pathway and Chronic Viral Infection

Virus infection can lead to increased expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 on the surface of antigen-specific T cells, inhibit proliferation of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, reduce secretion or spread of cytokines interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon gamma (IFN-gamma), and lead to decreased immune function or even failure of specific T lymphocytes.

This weakens the host's anti-infective immune response, leading to damage to the target organ, which ultimately leads to the development of related diseases such as persistent viral infection. This suggests that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may be one of the leading causes of chronic viral infection and chronic disease.

The PD-1/PD-L pathway has been shown to be associated with chronic viral infections such as HIV, HBV, HCV [11].

In chronic viral infection, CD8+T cells can be reactivated, proliferated and differentiated by blocking PD-1 with antibodies, and their virus-killing ability can be restored, resulting in decreased viral titer [12].

4.2.2 PD-1/PD-L and Autoimmune Disease

As a key co-inhibitory molecule, gene polymorphism of PD-1 is associated with susceptibility to autoimmune diseases, suggesting that PD-1 may play an important role in the occurrence and development of autoimmune diseases [13].

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

This is a systemic autoimmune disease. It was found that [14], the locus of PD-1 gene on human chromosome is exactly a highly sensitive candidate locus for SLE.

Abnormal frequency of PD-1 gene locus leads to decreased expression of PD-1, which leads to abnormal regulation of PD-1/PD-l signal pathway, leading to SLE.

Decreased expression of PD-1 is associated with the PD-1.3A/G allele, probably because the polymorphism of PD-1.3 disrupts the DNA binding site of Runt-related protein 1 and causes a decrease in the transcription level of PD-1 gene. It causes abnormal activation and proliferation of T cells and the like, thereby inducing the occurrence of SLE.

- PD-1/PD-L and Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by chronic synovitis and synovial hyperplasia.

T cells are involved in the occurrence of RA, and abnormal proliferation and differentiation of peripheral blood T cells initiate the occurrence of RA and promote chronic inflammatory response.

The level of PD-1 expressed on the surface of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the soluble PD-1 (sPD-1) in serum decreased in RA patients [15]. This indicates that PD-1 is involved in the development of rheumatoid arthritis by regulating the activity of T cells.

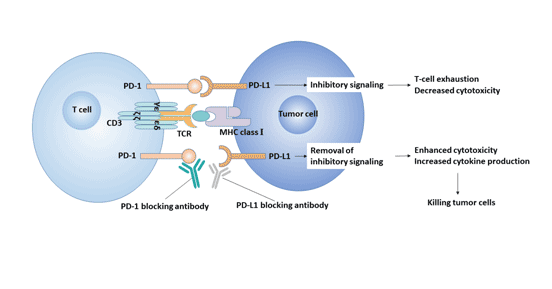

4.2.3 PD-1/PD-L and Tumor

In humans, antigens expressed in tumor tissue are recognized by host T cells but not necessarily eliminated.

One of the reasons is the up-regulated expression of PD-L1 and PD-1 in the tumor microenvironment. The expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues (such as lymphoma, choriocarcinoma, melanoma, esophageal cancer) and up-regulation of PD-1 expression on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are involved in related immunosuppressive signaling.

Activation of PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway inhibits proliferation and activation of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, inhibits the expression of cytokines, changes the tumor microenvironment. This promotes tumor cells to evade immune surveillance and killing [16]. Therefore, the PD-1/PD-L pathway has become a new target for the treatment of tumors.

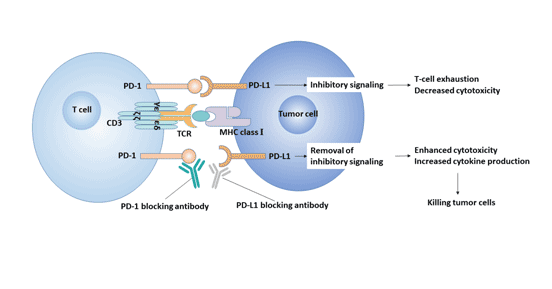

Figure 3. PD-1 / PD-L1 signaling pathway and tumor

5. Application of PD-1/PD-L in Therapy

PD-1 and PD-L1 signaling pathways play an important role in infection immunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation immunity, which makes targeting PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway a research hotspot for treating tumors.

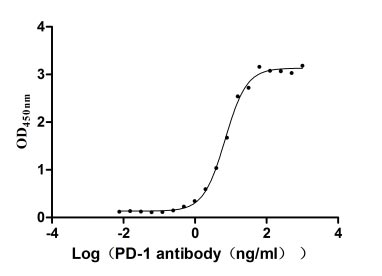

The development of immunological checkpoint blocker PD-1/PD-L1 antibody drugs is currently a research hotspot in the field of cancer therapy. PD-1/PD-L1 antibody, as one of the tumor immunotherapy methods, reverses the tumor immune microenvironment by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway and enhances the endogenous anti-tumor immune effect.

Antibodies acting on the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway are divided into two categories, including anti-PD-1 antibodies and anti-PD-L1 antibodies.Anti-PD-1 antibody can block the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 and PD-L2, while anti-PD-L1 antibody can only block the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1, but not the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L2.

At present, the main anti-PD-1/PD-1 antibodies are nivolumab, Pembrolizumab, ipidilizumab, avelumab, atezolizumab and durvalumab. Among them, nivolumab and pembrolizumab are PD-1 antibodies, and avelumab, atezolizumab and durvalumab are PD-L1 antibodies.

Nivolumab has been approved for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), bladder cancer (BC), microsatellite instability or mismatched repair defect (MSI-H/dMMR) colorectal cancer (CRC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), classic Hodgkin's lymphoma (cHL), melanoma, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

Pembrolizumab has been approved for use in melanoma, HNSCC, cervical cancer, cHL, NSCLC, BC, gastric cancer, and gastroesophageal cancer, as well as all advanced solid tumors classified as MSI-H/dMMR.

Avelumab has been approved for the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma and BC.

Atezolizumab has been approved for NSCLC and bladder cancer.

Durvalumab has been approved for the treatment of bladder cancer and NSCLC (phase III).

In the melanoma phase III clinical trial, the efficacy of the PD-1 antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab were recognized.

In addition, PD-1 antibodies have also been used in lung cancer and ovarian cancer.

6. Immune-Related Adverse Events of PD-1 Inhibitor

Although PD-1 inhibitors have surprising effects, they also induce immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

This may be due to the destruction of the body's immune homeostasis, which is maintained by the immune checkpoint [17]. In other words, by targeting and blocking negative regulatory factors such as immune checkpoints, the activity of T cells can be enhanced, leading to over-enhancement of immunity, which will inevitably cause damage to normal tissues while achieving anti-tumor effect.

References

[1] Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, et al. Induced expression of PD‐1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death [J]. The EMBO journal, 1992, 11(11): 3887-3895.

[2] Hams E, McCarron M J, Amu S, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 (programmed death ligand 1) enhances humoral immunity by positively regulating the generation of T follicular helper cells [J]. The Journal of Immunology, 2011, 186(10): 5648-5655.

[3] Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, et al. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion [J]. Nature medicine, 1999, 5(12): 1365.

[4] Latchman Y, Wood C R, Chernova T, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation [J]. Nature immunology, 2001, 2(3): 261.

[5] Ghiotto M, Gauthier L, Serriari N, et al. PD-L1 and PD-L2 differ in their molecular mechanisms of interaction with PD-1 [J]. International immunology, 2010, 22(8): 651-660.

[6] Keir M E, Butte M J, Freeman G J, et al. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity [J]. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 2008,26: 677-704.

[7] Sheppard K A, Fitz L J, Lee J M, et al. PD‐1 inhibits T‐cell receptor induced phosphorylation of the ZAP70/CD3ζ signalosome and downstream signaling to PKCθ [J]. FEBS letters, 2004, 574(1-3): 37-41.

[8] Chemnitz J M, Parry R V, Nichols K E, et al. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation [J]. The Journal of Immunology, 2004, 173(2): 945-954.

[9] Riley J L. PD‐1 signaling in primary T cells [J]. Immunological reviews, 2009, 229(1): 114-125.

[10] Ramsay A G. Immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy to activate anti‐tumour T‐cell immunity [J]. British journal of haematology, 2013, 162(3): 313-325.

[11] Hofmeyer K A, Jeon H, Zang X. The PD-1/PD-L1 (B7-H1) pathway in chronic infection-induced cytotoxic T lymphocyte exhaustion [J]. BioMed Research International, 2011, 2011.

[12] Watanabe T, Bertoletti A, Tanoto T A. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and T-cell exhaustion in chronic hepatitis virus infection [J]. Journal of viral hepatitis, 2010, 17(7): 453-458.

[13] Suarez-Gestal M, Ferreiros-Vidal I, Ortiz J A, et al. Analysis of the functional relevance of a putative regulatory SNP of PDCD1, PD1.3, associated with systemic lupus erythematosus [J]. Genes and immunity, 2008, 9(4): 309.

[14] Prokunina L, Castillejo-López C, Öberg F, et al. A regulatory polymorphism in PDCD1 is associated with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in humans [J]. Nature genetics, 2002, 32(4): 666.

[15] Li S, Liao W, Chen M, et al. Expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1) on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in rheumatoid arthritis [J]. Inflammation, 2014, 37(1): 116-121.

[16] Quezada S A, Peggs K S. Exploiting CTLA-4, PD-1 and PD-L1 to reactivate the host immune response against cancer [J]. British journal of cancer, 2013, 108(8): 1560.

[17] Michot J M, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review [J]. European journal of cancer, 2016, 54: 139-148.

CUSABIO team. PD-1-- An Important Immune Checkpoint. https://www.cusabio.com/c-20975.html

Comments

Leave a Comment