It is well-recognized that inflammation and immune escape are two hallmarks of tumors. Importantly, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), and bone marrow-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are the major immune cell components in numerous tumors. Of these, TAMs lie at the centre of tumor microenvironment (TME).

Intriguingly, it has been shown that when the TEM changes, TAMs can change their functional phenotype to influence the development and metastasis of tumors. But how do the altered metabolic phenotype of TAMs in TME help TAMs to accomplish the functional switch? What's the relationship between TAMs metabolism and TME? The questions have attracted a great deal of interest from researchers. After reading this article, you might have some insight into these.

1. What is the Tumor Microenvironment?

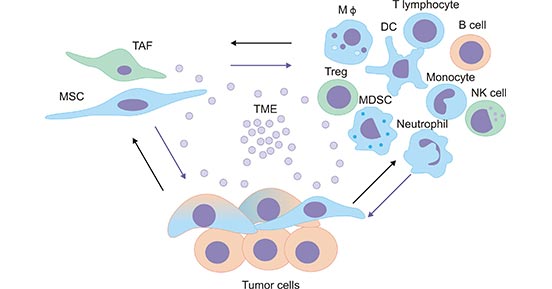

The tumor microenvironment (TME), is mainly composed of immune cells, such as macrophages, T lymphocytes, natural killer cells (NK cells), dendritic cells, and neutrophils, etc (Figure 1) [1]. The interactions between cells play a crucial role in the development of TME, and their metabolic products not only serve as a source of energy supply, but also mediate the communication between cells in the TME.

Figure 1. The tumor microenvironment

*This figure is derived from the publication on Mediators of inflammation Journal [1]

2. What are Tumor-Associated Macrophages?

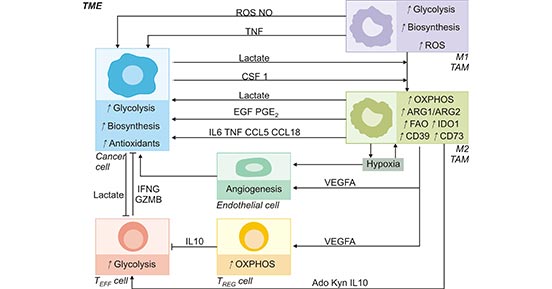

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are the main immune population in TME. TAMs constitute as much as 50% of certain solid tumors. TAMs exert a wide range of effects on TME by synthesizing and secreting a variety of cytokines [2]. In the microenvironment, TAMs are broadly categorized as M1 or M2 types that perform different functions in cells. M1-like TAMs (TAM1) have high levels of aerobic glycolytic and can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill pathogens to mediate antitumor process. In contrast, M2-like TAMs (TAM2) depend on high levels of oxidative phosphorylation and can produce IL-10 and VEGF to promote the growth of tumor cells [3]. Thus, the metabolic profile of TAMs is dynamic and has a major influence not only on TAM survival but also on tumor progression (Figure 2) [4].

Figure 2. TAMs metabolism in the tumor microenvironment

*This figure is derived from the publication on Cell metabolism [4]

Emerging evidence indicates that the behavior of TAMs from the metabolic change affects disease progression and outcome in cancer, which helps to develop potential targets for novel antitumor therapies. Next, we will introduce these metabolic shifts are affecting TAMs behavior and thus impact on disease outcome.

3. The Metabolic Phenotype of Tumor-Associated Macrophages

3.1 Glucose Metabolism in TAMs

There are essential differences in glucose metabolism between tumor cells and normal cells. We know that metabolic activities in normal cells rely primarily on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to generate ATP for energy. However, one of the metabolic features of cancer cells is to avidly take up glucose for aerobic glycolysis. This inefficient pathway for energy production in cancer cells was known as the Warburg effect [5]. In TME, TAMs are also depend on high rates of glycolysis for growth and survival, resulting in competition for glucose in TEM.

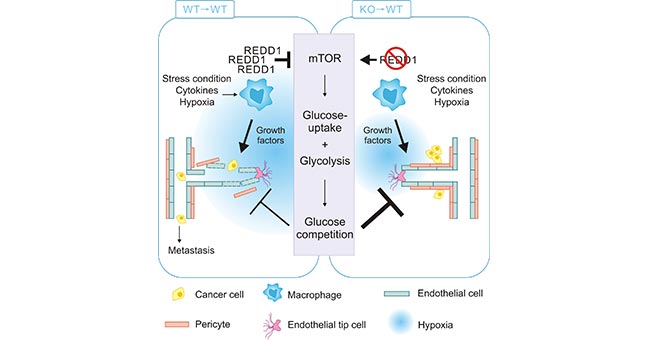

TAMs can promote tumor progression by providing nutritional support, mainly through the recruitment and activation of vascular epithelial cells by secreting VEGFA, ADM, CXC chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) and CXCL12, which provide nutrients for tumor growth and thus promote tumor angiogenesis. The process contributes to the reduced oxygen in the environment [6, 7]. Studies have shown that under hypoxic conditions, TAMs promote REDD1 (regulated in development and in DNA damage response 1), but inhibit mTOR pathway. Meanwhile, the hypoxic conditions inhibit the uptake of glucose in TAMs, suppressing TAMs glycolysis. As a result, this leads to the increased glucose in TME and enhanced the glycolysis in TME, promoting the tumor growth [8]. On the other hand, REDD1-deficient TAMs are able to compete with neighboring endothelial cells for glucose by activating mTOR pathway and increasing glycolysis, thus promoting vascular normalization and inhibiting tumor metastasis (Figure 3) [8].

Figure 3. REDD1-deficient TAMs enhance glycolysis via activating mTOR pathway

*This figure is derived from the publication on Cell metabolism [8]

Glucose metabolism in TAMs provides novel therapeutic opportunities for the treatment of tumors. It has been found that TAMs from human pancreatic cancer (PDCA) have high glycolytic activity. Using 2-deoxyglucose (2DG), a competitive inhibitor of HK2, can inactive the functional phenotype of the cells [9]. In several in vitro and in vivo studies, 2DG in combination with targeted therapies effectively inhibited cancer cell viability, proliferation, and metastasis [10]. Besides HK2, the key enzymes of glycolysis are phosphofructokinase 2 (PFK2), phosphoglycerol kinase 1 (PGK1), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), pyruvate kinase 2 (PKM2), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), and enolase (ENO1). Thus, inhibiting glycolytic enzymes' activities could be useful strategies for cancer therapy. Currently, it is essential to further understand the mechanisms related to TAMs glycolysis and to find the potential targets in TAMs glycolytic process.

3.2 Lipid Metabolism in TAMs

In addition to glucose metabolism, there are also changes in lipid metabolism. It was found that macrophage-induced COX2 expression promoted tumor growth and angiogenesis in lung cancer mouse models [11]. In addition, TAMs have high levels of long chain fatty alcohol oxidase (FAO). The in vivo experiments showed that inhibition of FAO polarized TAMs from M2 to M1 type in lung and colon cancer mouse models [12, 13]. In contrast, macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) released from tumor cells induces TAMs to overexpress fatty acid synthase (FASN), which actives peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (PPARD). Then it triggers the release of immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10, which induces the M2 polarization of TAMs [14-16].

Despite the increased FAO levels of TAMs, TAMs in the certain TME could accumulate intracellular lipids to sustain their own metabolism, which exerts immunomodulatory effects in TAMs. In this case, the protein expression of intracellular lipid metabolism is aberrantly regulated in the TAMs, such as autolytic enzyme structural domain 5 protein (ABHD5), monoglyceride lipase (MGLP), fatty acid binding protein (FABP) and medium chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (ACADM) [17, 18]. In the early stages of tumor development, TAMs overexpress FABP5, leading to the release of type I interferon (IFN-1), promoting anti-tumor immune response. In contrast, in the advanced stages, TAMs highly express FABP4, which promotes IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby promoting tumor development [17, 18].

Regarding the mechanism of lipid metabolism in TAMs, further studies are still needed to reveal the correlation between lipid metabolism and tumors. Some key enzymes and polarization mechanisms in the lipid metabolism are expected to provide a new approach for tumor diagnosis and treatment.

3.3 Amino Acid Metabolism in TAMs

There are a few studies that have identified a possible effect of amino acid metabolism on functional shifts of TAMs. Although most of these studies are observational, rarely involve mechanistic studies. Researchers suggested that elevated expression of arginase-1 (ARG1) was found in TAMs in various tumor mouse models. ARG1 has been considered as a marker of M2-like TAMs. However, the role of high ARG1 expression in TAMs on malignancy remains unclear. Both hypoxia and increased lactate promote ARG1 expression. In lung cancer mouse models, knockdown of ARG1 resulted in significantly smaller tumor volume in mice [15].

It was also found that ARG2 and the rate-limiting enzyme, indoleamine-2, 3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), both degrades arginine and tryptophan, which are essential for the nutritional metabolism of immune effector cells. The process leads to dysfunction of T and NK cells [11]. It implies that TAMs can induce immunosuppressive effects by triggering the depletion of these amino acids in TME, which in turn disrupts immune surveillance. Thus, it is clear that the enzymes involved in the amino acid metabolism of TAMs have an important role in the metabolic mechanism of TAMs.

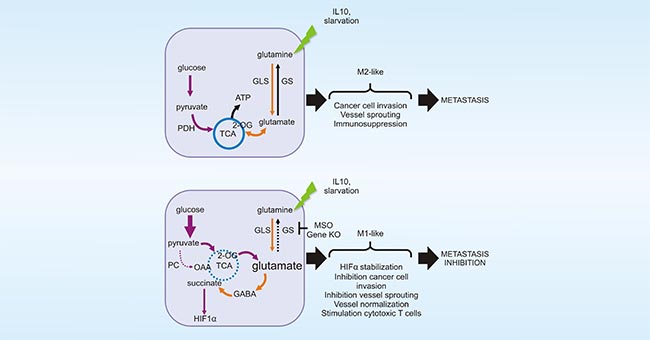

Figure 4. GLUL promotes the M2 polarization of TAMs

*This figure is derived from the publication on Cell reports [20]

As previously mentioned, macrophages are highly plastic cells. As shown in Figure 4, in vitro experiments have demonstrated that glutamine ligase (GLUL) promotes the M2 polarization of TAMs by catalyzing the conversion of glutamate to glutamine (Gln). Inhibition of Gln uptake could induce M1 polarization of TAMs in tumor mouse models [12]. The polarization of TAM2 to TAM1 is expected to enhance phagocytosis of TAMs against tumors, which is also considered as a promising strategy for the alternative tumor therapy.

3.4 Iron Homeostasisin in TAMs

Among the alternative therapies for cancer, nutritional elements involved in cellular metabolic processes are considered as potential targets for cancer therapy. With the increasing understanding of metabolic fields, metallic elements (such as Fe, Cu, and Zn) have been found to be involved in various key processes of biological cell growth and development (including cancer). Among the many metallic elements, iron (Fe) is an important essential trace element for living organisms and has an important role in cellular metabolism and regulation processes.

Only a few studies have shown that abnormal iron release in TAMs is associated with tumorigenesis, proliferation and metastasis. As mentioned previously, TAMs provide nutrients to tumor abnormal blood vessels, which also results in hypoxia to varying degrees [6, 7]. Hypoxia in TMEs could upregulate the expression levels both TAMs solute carrier family 40 member 1 (SLC40A1) and lipid carrier protein 2 (LCN2), which will further inhibit the uptake of iron in TAMs. On the other hand, it leads to iron release in TMEs and enhances tumor cell proliferation. The uptake of iron further enhances oxidative stress and activates signaling pathways such as signal transduction and activation transcription factor 3 (STAT3) and nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB), which finally promotes tumor development [21, 22].

We know that tumor cells exhibit a strong dependence on iron and are also more susceptible to iron deficiency. Despite a large number of studies, the specific mechanism between iron and cancer is still not fully explained. Studying the mechanism of iron homeostasis in TAMs may provide new ways of cancer therapies.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the research of anti-tumor immunotherapy targeting TAMs. On the one hand, the main cause of enhanced glycolysis in tumor cells is related to the enhanced expression and activity of glycolytic enzymes. It was found that inhibiting or promoting the glycolytic process of TAMs would affect TEM tumor cell progression. Some key enzymes, as new highly sensitive tumor markers, have shown great potential in the diagnosis and prognosis of malignant tumors. On the other hand, TAMs contain two isoforms that can polarize each other: TAM1 play a role in inhibiting tumor growth, while TAM2 serves as a tumor-promoting role. During tumor development, TAMs tend to polarize more into TAM2.

Based on the functional characteristics of the two subtypes of TAMs, researchers expect to alter TAMs polarization through TAMs metabolic reprogramming to enable TAMs to exert anti-tumor effects. However, future studies will be needed to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of TAMs metabolic mechanisms on tumor development, which holds great potential for antitumor immunotherapy.

References

[1] Trivanović, Drenka, et al. "The roles of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells in tumor microenvironment associated with inflammation." Mediators of inflammation (2016).

[2] Vinogradov, Serguei, Galya Warren, and Xin Wei. "Macrophages associated with tumors as potential targets and therapeutic intermediates." Nanomedicine (2014): 695-707.

[3] Lin, Yuxin, Jianxin Xu, and Huiyin Lan. "Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor metastasis: biological roles and clinical therapeutic applications." Journal of hematology & oncology (2019): 76.

[4] Vitale, Ilio, et al. "Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment." Cell metabolism (2019): 36-50.

[5] Jeong, Hoibin, et al. "Tumor-associated macrophages enhance tumor hypoxia and aerobic glycolysis." Cancer research (2019): 795-806.

[6] Biswas SK, Allavena P, Mantovani A. “Tumor-associated macrophages: functional diversity, clinical significance, and open questions.” InSeminars in immunopathology (2013): 585-600.

[7] Hughes, Russell, et al. "Perivascular M2 macrophages stimulate tumor relapse after chemotherapy." Cancer research (2015): 3479-3491.

[8] Wenes, Mathias, et al. "Macrophage metabolism controls tumor blood vessel morphogenesis and metastasis." Cell metabolism (2016): 701-715.

[9] Rabold, Katrin, et al. "Cellular metabolism of tumor‐associated macrophages–functional impact and consequences." Febs Letters (2017): 3022-3041.

[10] Netea-Maier, Romana T., Johannes WA Smit, and Mihai G. Netea. "Metabolic changes in tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages: a mutual relationship." Cancer letters (2018): 102-109.

[11] Nakao, Shintaro, et al. "Infiltration of COX-2–expressing macrophages is a prerequisite for IL-1β–induced neovascularization and tumor growth." The Journal of clinical investigation (2005): 2979-2991.

[12] Liu, Pu-Ste, et al. "α-ketoglutarate orchestrates macrophage activation through metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming." Nature immunology (2017): 985-994.

[13] Choi, Judy, et al. "Glioblastoma cells induce differential glutamatergic gene expressions in human tumor-associated microglia/macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages." Cancer biology & therapy (2015): 1205-1213.

[14] Jha, Abhishek K., et al. "Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization." Immunity (2015): 419-430.

[15] Brüne, Bernhard, Andreas Weigert, and Nathalie Dehne. "Macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment." Redox Biology (2015): 419.

[16] Hossain, Fokhrul, et al. "Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation modulates immunosuppressive functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and enhances cancer therapies." Cancer immunology research (2015): 1236-1247.

[17] Hao, Jiaqing, et al. "Expression of adipocyte/macrophage fatty acid–binding protein in tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer progression." Cancer research (2018): 2343-2355.

[18] Xiang, Wei, et al. "Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates cannabinoid receptor 2-dependent macrophage activation and cancer progression." Nature communications (2018): 1-13.

[19] Carmona-Fontaine, Carlos, et al. "Metabolic origins of spatial organization in the tumor microenvironment." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2017): 2934-2939.

[20] Palmieri, Erika M., et al. "Pharmacologic or genetic targeting of glutamine synthetase skews macrophages toward an M1-like phenotype and inhibits tumor metastasis." Cell reports (2017): 1654-1666.

[21] Mertens, Christina, et al. "Intracellular iron chelation modulates the macrophage iron phenotype with consequences on tumor progression." PloS one (2016): e0166164.

[22] Ören, Bilge, et al. "Tumour stroma‐derived lipocalin‐2 promotes breast cancer metastasis." The Journal of pathology (2016): 274-285.

CUSABIO team. The Metabolic Phenotype of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in the Tumor Microenvironment. https://www.cusabio.com/c-21002.html

Comments

Leave a Comment