Poliovirus

Poliovirus (PV) is a typical picornavirus belonging to the genus enterovirus of the Picornaviridae family. It is usually transmitted through faecal-oral and respiratory routes. Most infected people either show no symptoms or mild symptoms, but paralytic poliomyelitis (polio) occurs in 0.1–1% of cases. There are three wild PV serotypes: WPV1, WPV2 and WPV3, with one no immunity to heterologous serotypes. Humans are the exclusive natural host, although primates and old world monkeys can be experimentally infected.

1. The Structure of Poliovirus

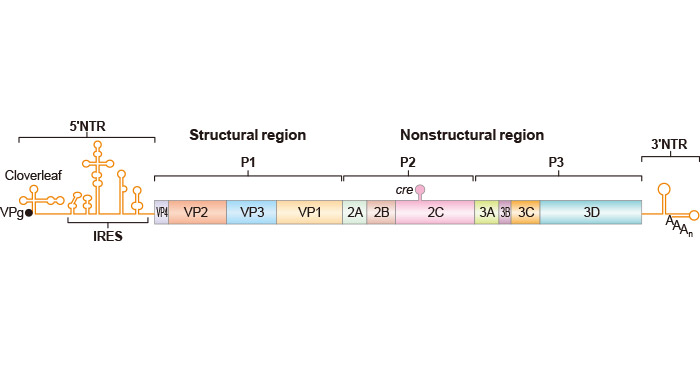

Poliovirus is a positive-sense, single-stranded (ss) RNA virus with about 30 nm in diameter. The virion has a non-enveloped icosahedral capsid that contains sixty copies of each of four capsid proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4, which encapsulate a single strand of messenger sense RNA [1]. The RNA genome is approximately on average 7.4 kb in length. The uncertainty of the genome length is due to the heterogeneity of the 3'-terminal poly (A) tail [2].

Figure 1. shows essential domains of the genome: the 5'-terminal covalently linked protein VPg (3B in the polyprotein), the long 5'-terminal nontranslated region (5'NTR) containing the cloverleaf (essential for genome synthesis), and the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) that controls initiation of the polyprotein (open box) at nt 743. The polyprotein has been divided into three domains (P1, P2, P3) of which P1 is the precursor to four capsid proteins VP1–4. P2 and P3 specify replication proteins. cre mapping to the coding region of P2 is the essential cis-acting (RNA) replication element. The 3'NTR consists of two stem loops and the 3'-terminal poly (A) tail of varying lengths [3].

Figure 1. The essential domains of the genome of Poliovirus

*This diagram is derived from the publication published on Annu. Rev. Microbiol [4]

Three serotypes of poliovirus are antigenically distinct that just means that your body requires 3 different kinds of antibodies to fight all 3 types of poliovirus and having immunity to one type does not protect you from the other types. But all three have 70% nucleotide identity.

2. Poliovirus Infection and Life Cycle

Poliovirus infection in humans generally initiates through the oral ingestion of the virus. Once inside the body, the poliovirus reaches the intestine, where the virus finds a cell with the correct receptor, initiating the infection. The poliovirus then replicates in the alimentary tract.

2.1 Viral Entry

Poliovirus enters the host cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Poliovirus binds to the poliovirus receptor (PVR)/CD155 on the host cell surface, triggering a rearrangement of capsid proteins. The VP1 capsid protein is incorporated into the plasma membrane, creating a protein channel through which the RNA genome is released into the cellular cytoplasm.

2.2 Viral Replication

Upon entry into the cytoplasm, the viral RNA functions as mRNA and is translated using the host cell machinery to synthesize a single polyprotein that is cotranslationally processed into four capsid proteins and seven non-structural proteins, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C and 3D, that are involved in viral replication. The initiation of virus-specific translation starts with ribosomes entering the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) within the 5′ noncoding sequence of the RNA.

The viral proteins include:

2.3 Viral Assembly

Following translation, the viral genome undergoes replication, generating positive-sense copies of the original genome. This process entails the generation of multiple negative-sense copies, which subsequently serve as templates for the synthesis of positive-sense strands. The protein VPg acts as a primer for both positive and negative sense strands.

The viral proteins assemble into a pentameric intermediate, subsequently transforming into an empty capsid containing 60 copies each of VP0, VP3, and VP1. During this process, five copies of VP1, VP3, VP2, and VP4 become the interior surface of the viral capsid. Each capsid encapsidates a copy of the geomic RNA to form the virus particle. The synthesized poliovirus virions are released from the host cell through cell lysis into the bloodstream.

From the initial sites of replication, the virus disseminates to nearby lymph nodes (cervical and mesenteric) and the bloodstream, possibly infecting extraneural tissues and amplifying viremia. Polioviruses can breach the intestinal epithelium barrier and cross the blood-brain barrier to reach the central nervous system (CNS), particularly the spinal cord, leading to the destruction of motor neurons and instigating acute paralytic poliomyelitis.

3. Immune Avoidance of Poliovirus

Poliovirus evades the immune system using two key mechanisms. First, it can withstand the highly acidic conditions in the stomach, enabling the virus to infect the host and disseminate throughout the body via the lymphatic system. Secondly, due to its rapid replication, the virus outpaces the immune response, overwhelming the host organs before an effective defense can be initiated.

Through antigenic variation in its surface proteins, particularly the capsid proteins, the virus evades recognition by the immune system. It inhibits the interferon response, crucial for antiviral defense, and tends to replicate in immune-protected sites such as the gastrointestinal tract and lymphoid tissues. By invading nerve cells and modulating host cell defense mechanisms, poliovirus can establish persistent infections, contributing to its ability to cause paralytic disease.

4. Recent Research and Advances

Novel Vaccine Development: A cost-effective, cold chain-free booster vaccine using poliovirus capsid protein (VP1) fused with cholera non-toxic B subunit (CTB) expressed in lettuce chloroplasts shows promise for protection against all three poliovirus serotypes [5].

Global Polio Eradication Progress: The global effort toward poliovirus eradication is progressing. Certification of eradication for wild poliovirus types 2 and 3 has been achieved. Occasional cases of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) are linked to low oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) coverage [6-7].

OPV2 Withdrawal: The withdrawal of the serotype 2 component of OPV (OPV2) in 2016 aimed to prevent VDPV2 emergence. Statistical models estimate the emergence date and source of VDPV2s detected between 2016 and 2019 [8].

Attenuation Strategies: Codon deoptimization and genome modifications have been explored to further attenuate Sabin OPV2, showing potential for achieving complete poliovirus eradication [9-10].

Impact of COVID-19: The COVID-19 pandemic has posed challenges to polio eradication efforts, leading to disruptions in immunization activities and surveillance [11].

Community Transmission: The second identification of community transmission of poliovirus in the United States since 1979 is reported, emphasizing the need for continued vigilance [12].

References:

[1] Hogle JM, Chow M, Filman DJ. 1985. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 A resolution [J]. Science 229:1358–1365.

[2] van Ooij MJ, Polacek C, et al. Polyadenylation of genomic RNA and initiation of antigenomic RNA in a positive-strand RNA virus are controlled by the same cis-element [J]. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34:2953–65.

[3] Wimmer E, Paul AV. 2010. The making of a picornavirus genome [J]. In The Picornaviruses, ed. E Ehrenfeld, E Domingo, RP Roos, pp. 33–55. Washington, DC: ASM Press.

[4] Eckard Wimmer and Aniko V. Paul. Synthetic Poliovirus and Other Designer Viruses: What Have We Learned from Them [J]? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011. 65:583–609.

[5] H. Daniell, V. Rai, Yuhong Xiao. Cold Chain and Virus‐free Oral Polio Booster Vaccine Made in Lettuce Chloroplasts Confers Protection Against All Three Poliovirus Serotypes [J]. PLANT BIOTECHNOLOGY JOURNAL, 2019.

[6] Sharon A. Greene, Jamal A. Ahmed, S. Datta, et al. Progress Toward Polio Eradication — Worldwide, January 2017–March 2019 [J]. MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT, 2019.

[7] J. Jorba, O. Diop, Jane Iber, Elizabeth Henderson, et al. .Update on Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks — Worldwide, January 2018–June 2019 [J]. MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT, 2019.

[8] G R Macklin, K M O'Reilly, N C Grassly, et al. Evolving Epidemiology of Poliovirus Serotype 2 Following Withdrawal of The Serotype 2 Oral Poliovirus Vaccine [J]. SCIENCE (NEW YORK, N.Y.), 2020.

[9] Jennifer L Konopka-Anstadt, Ray Campagnoli, et al. Development of A New Oral Poliovirus Vaccine for The Eradication End Game Using Codon Deoptimization [J]. NPJ VACCINES, 2020.

[10] Ming Te Yeh, Erika Bujaki, Patrick T Dolan, et al. Engineering The Live-Attenuated Polio Vaccine to Prevent Reversion to Virulence [J]. CELL HOST & MICROBE, 2020.

[11] A. Chard, S. D. Datta, G. Tallis, et al. Progress Toward Polio Eradication — Worldwide, January 2018–March 2020 [J]. MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT, 2020.

[12] R. Link-Gelles, E. Lutterloh, Patricia Schnabel Ruppert, et al. Public Health Response to A Case of Paralytic Poliomyelitis in An Unvaccinated Person and Detection of Poliovirus in Wastewater — New York, June–August 2022 [J]. MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT, 2022.