A growth factor, which generally considered as a series of cytokines, is a naturally occurring substance that stimulate cell growth, differentiation, survival, inflammation, and tissue repair. Usually it is a protein or a steroid hormone. Growth factors are important to regulate a variety of cellular processes, which can be secreted by neighboring cells, distant tissues and glands, or even tumor cells themselves. Normal cells show a demand for several growth factors to maintain proliferation and viability. Growth factors can exert their stimulation though endocrine, paracrine or autocrine mechanisms.

2. Featured Growth Factors & Receptors

Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) and Receptors

a. Fibroblast growth factors

The fibroblast growth factors are a family of cell signaling proteins, also known as potent regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation and function, which are critically important in normal development, tissue maintenance, wound repair and angiogenesis. FGFs are also associated with several pathological conditions. Mutations in FGF genes are associated with various diseases such as cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, hepatocellular carcinoma, intervertebral disc homeostasis and hypophosphatemia[11][12][13].

FGFs bind heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (HSGAGs), which facilitates dimerization (activation) of FGF receptors (FGFRs). There are 22 members of the FGF family in humans from FGF-1 to FGF-23 except for FGF-15 which exists in the mouse. All FGFs except for four members (FGF11-FGF14) bind to FGF Receptors. Because FGF11-FGF14, also known as fibroblast growth factor-homologous factors or FHF1-FHF4, share significant sequence and structural homology with FGFs, and the manner of binding HS is similar to the FGFs. In contrast, Olsen et al. And Mohammadi et al. Who analysed FHF-mediated FGFR activation showed that FHFs are incapable of activating any of the four FGFRs, likely as a result of the structural incompatibility of the FGFR interacting region[14][15]. According to the present stage of knowledge, FHFs act as intracellular signaling molecules that function independently of FGFRs, via interaction with islet brain-2 scaffold protein and voltage-gated sodium channels, as discussed in detail later[16]. Based on phylogenetic analysis, the human FGF family can be further divided into seven subfamilies; FGF1-FGF2, FGF4-FGF6, FGF 3/7/10/22, FGF 8/17/18, FGF 9/16/20, FGF 11-FGF14, and FGF 19/21/23. Some oher research discoveries showed that FGF24 and 25 are exist in zebra fish, but no data is available about their mammalian counterparts[17][18].

b. Fibroblast growth factors receptors

The fibroblast growth factor receptors, also known as FGFRs, are receptors that bind to members of the fibroblast growth factor family of proteins. FGFRs are single-pass transmembrane receptors with extracellular ligand-binding domains and an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain that have intracellular tyrosine kinase activity, and belong to the family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK)[19]. Activation of RTKs by their respective ligands induces kinase activation that in turn initiates intracellular signaling networks that ultimately orchestrate key cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, growth, differentiation, migration, and survival. In this way, RTKs play pivotal biological roles during the development and adult life of multicellular organisms. FGFRs are associated with several pathological conditions, such as cancer cell migrations[20], tumor initiation and progression[21], carcinogenesis[22], congenital skeletal dysplasias[23], et al. Mutations in FGFR genes are associated with various diseases such as breast cancer[24], bladder cancer[25], gastric cancer[26], clear-cell renal cell carcinoma[27], developmental corruption and malignant disease[28], et al.

The FGFRs includes four genes encoding closely related transmembrane, tyrosine kinase receptors (termed FGFR1 to FGFR4). A typical FGFR consists of a signal peptide that is cleaved off, three immunoglobulin (Ig)–like domains, an acidic box, a transmembrane domain, and a split tyrosine kinase domain.

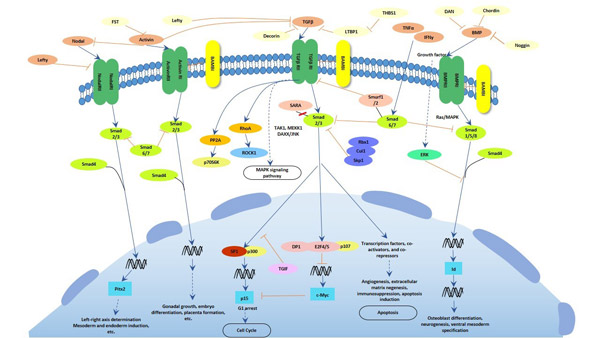

Transforming growth factors & receptors

a. Transforming growth factors

Transforming growth factor, also known as Tumor growth factor, or TGF, is used to refer to two classes of polypeptide growth factors, Transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα) and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ). TGFα and TGFβ are autocrine/paracrine growth factors that are classically thought of as potent promoters and inhibitors of cell growth, respectively, in normal tissues[29][30][31].

TGFα is upregulated in some human cancers and acts through the EGF receptor. It is produced in macrophages, keratinocytes and brain cells, and induces epithelial development. TGFα is also thought to be invovlved in the pathogenesis process of hepatocarcinogenesis. TGFβ acts through the TGFβ receptor (TGFβR) and exists in three known isoforms in humans, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3[32], which are upregulated in colorectal adenomas and cancer, and directly associated with more advanced tumor characteristics[33][34]. Moreover, they also play crucial roles in tissue regeneration, cell differentiation, embryonic development, and regulation of the immune system. Isoforms of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1) are also involved in the pathogenesis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the NF-κB pathway[35]. TGFβ receptors are single pass serine/threonine kinase receptors[36].

b. Transforming growth factors receptors

In the last paragraph, we have introduced that the receptor of TGFα is epidermal growth factor receptor ( also known as EGFR), which is a transmembrane protein that is a receptor for members of the epidermal growth factor family (EGF family) of extracellular protein ligands, and the receptor of TGFβ also has three isoforms in humans, TGFRI, TGFRII and TGFRIII.

EGFR is a transmembrane protein that is activated by binding of its specific growth factor ligands, including TGFα and epidermal growth factor. Upon activation by its specific ligands, EGFR turns to be a transition from an inactive monomeric form to an active homodimer. Mutations that EGFR overexpression, also known as upregulation or amplification, have been associated with several cancers, including squamous-cell carcinoma of the lung, anal cancers, glioblastoma and epithelian tumors of the head and neck[37]. Aberrant EGFR signaling has been implicated in inflammatory disease and monogenic disease. Furthermore, EGFR also has been reported to play a critical role in TGFβ1 dependent fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation[38].

The Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGFβ) receptors are a superfamily of serine/threonine kinase receptors. There are three isoforms receptors bind members of the TGFβ superfamily of growth factor, TGFRβ1, TGFRβ2, TGFRβ3, can be distinguished by their structural and functional properties. TGFβR1 (also known as ALK5) and TGFβR2 have similar ligand-binding affinities and can be differentiated from each other just by peptide mapping. Both TGFβR1 and TGFβR2 have a high affinity for TGFβ1 and low affinity for TGFβ2. TGFβR3 (also known as β-glycan) has a high affinity for both homodimeric TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 and the heterodimer TGF-β1.2. The TGFβ receptors also bind TGFβ3.

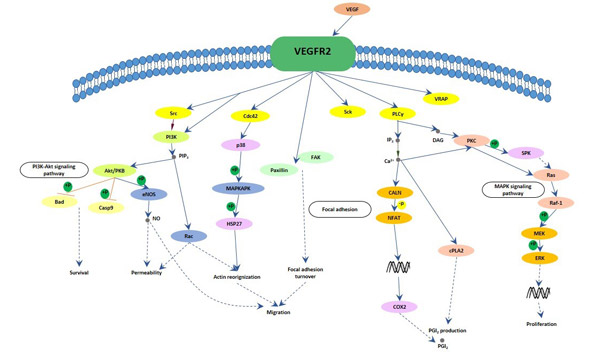

Vascular endothelial growths factor and Receptors

a. Vascular endothelial growth factors

Vascular endothelial growth factors, also known as vascular permeability factor (VPF), or VEGF, constitute a sub-family of growth factors produced by cells that stimulate the formation of blood vessels and a mitogen for vascular endothelial cells. VEGFs are important signaling proteins involved in both vasculogenesis, the de novo formation of the embryonic circulatory system, and angiogenesis, the growth of blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature. There are five members in the vascular growth factor family, include VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D and placenta growth factor (PlGF). VEGF-A is the first discovery member of the vascular endothelial growth factor family. Vascular endothelial growth factors are key mediators of angiogenesis that is crucial for development and metastasis of tumors. Overexpression of VEGF can contribute to disease. Solid cancers cannot grow beyond a limited size without an adequate blood supply; cancers that can express VEGF are able to grow and metastasize. When VEGF is overexpressed, it can cause vascular disease in the retina of the eye and other parts of the body. Drugs can inhibit VEGF and control or slow those diseases, such as aflibercept, bevacizumab, ranibizumab and pegaptanib sodium (Macugen).

b. Vascular endothelial growth factor Receptors

All members of the VEGF family stimulate cellular responses by binding to tyrosine kinase receptors (the VEGFRs) on the cell surface, causing them to be dimer and become activated through transphosphorylation. The VEGFRs have an extracellular portion, which is consist of 7 immunoglobulin-like domains, a single transmembrane spanning region and an intracellular portion containing a split tyrosine-kinase domain. There are three main subtypes of VEGFR, numbered 1, 2 and 3, also known as Flt-1, KDR/Flk-1 and Flt-4, respectively.

VEGF-A binds to VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) and VEGFR-2 (KDR/Flk-1). VEGFR-2 appears to mediate almost all of the known cellular responses to VEGF, which can combines with VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D and VEGF-E[39]. Although VEGFR-1 is thought to modulate VEGFR-2 signaling, the function of VEGFR-1 is less well defined. Another function of VEGFR-1 is to act as a dummy/decoy receptor, sequestering VEGF from VEGFR-2 binding. In fact, an alternatively spliced form of VEGFR-1 (sFlt1) is not a membrane bound protein but is secreted and functions primarily as a decoy[40]. A third receptor has been discovered (VEGFR-3), however, VEGF-A is not a ligand for this receptor. VEGFR-3 mediates lymphangiogenesis by binding to VEGF-C and VEGF-D.

References

[1] Stauber DJ, DiGabriele AD, et al. Structural interactions of fibroblast growth factor receptor with its ligands[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000, 97 (1): 49–54

[2] Santos-Ocampo S, Colvin JS, et al. Expression and biological activity of mouse fibroblast growth factor-9[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996, 271 (3): 1726–31

[3] Ornitz DM, Xu J, et al. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family [J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996, 271(25):15292-15297

[4] Duchesne L, Tissot B, et al. N-glycosylation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 regulates ligand and heparan sulfate co-receptor binding [J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006, 281(37):27178-27189

[5] Davidson D, Blanc A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 18 signals through FGF receptor 3 to promote chondrogenesis[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005, 280(21):20509-20515

[6] Chellaiah A, Yuan W, et al. Mapping ligand binding domains in chimeric fibroblast growth factor receptor molecules. Multiple regions determine ligand binding specificity[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999, 274 (49): 34785–94

[7] Pavel Krejci, Jirina Prochazkoval, et al. Molecular pathology of the fibroblast growth factor family[J]. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30(9): 1245–1255

[8] Laureys G, Barton DE, et al. Chromosomal mapping of the gene for the type II insulin-like growth factor receptor/cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor in man and mouse[J]. Genomics.1988, 3 (3): 224–9

[9] Ojeda, S. R.; Ma, Y. J., et al. The transforming growth factor alpha gene family is involved in the neuroendocrine control of mammalian puberty[J]. Molecular Psychiatry. 1997, 2 (5): 355–358

[10] Gilchrist, R., Lane, M., et al. Oocyte-secreted factors: regulators of cumulus cell function and oocyte quality[J]. Human Reproduction Update. 2008, 14(2), pp.159-177

[11] Yun, Y.-R., Won, J. E., et al. Fibroblast growth factors: biology, function, and application for tissue regeneration[J]. Tissue Eng. 2010, 218142

[12] Coleman SJ, Grose RP, et al. Fibroblast growth factor family as a potential target in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2014, 29;1:43-54

[13] Ellman MB, An HS, et al. Biological impact of the fibroblast growth factor family on articular cartilage and intervertebral disc homeostasis[J]. Gene. 2008, 15;420(1):82-9

[14] Olsen SK, Garbi M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) homologous factors share structural but not functional homology with FGFs[J]. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278:34226–34236

[15] Mohammadi M, Dikic I, et al. Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction[J]. Mol Cell Biol. 1996; 16:977–989

[16] Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors: evolution, structure, and function[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005; 16:215–220

[17] Roy NM, Sagerstrom GG. An early Fgf signal required for gene expression in the zebrafish hindbrain primordium[J]. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004; 148(1): 27-42

[18] Katoh Y, Katoh M. Comparative genomics on FGF7, FGF10, FGF22, orthologs, and identification of fgf25[J]. Int J Mol Med. 2005; 16(4): 767-70

[19] Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases[J]. Cell. 2000, 103:211–25

[20] Nguyen T, Mège RM. N-Cadherin and Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors crosstalk in the control of developmental and cancer cell migrations[J]. Eur J Cell Biol. 2016, 95(11):415-426

[21] Feng S, Zhou L, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors: multifactorial-contributors to tumor initiation and progression[J]. Histol Histopathol. 2015, 30(1):13-31

[22] Haugsten EM, Wiedlocha A, et al. Roles of fibroblast growth factor receptors in carcinogenesis[J]. Mol Cancer Res. 2010, 8(11):1439-52

[23] Sanak M. Molecular genetics of congenital skeletal dysplasias related to mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptors[J]. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 1999, 3(1):67-82

[24] Wang S, Ding Z. Fibroblast growth factor receptors in breast cancer[J]. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39(5):1010428317698370

[25] Morales-Barrera R, Suárez C, et al. Targeting fibroblast growth factor receptors and immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of advanced bladder cancer: New direction and New Hope[J]. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016, 50:208-216

[26] Inokuchi M, Fujimori Y, et al Therapeutic targeting of fibroblast growth factor receptors in gastric cancer[J]. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015, 2015:796380

[27] Sonpavde G, Willey CD, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors as therapeutic targets in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma[J]. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014, 23(3):305-15

[28] Kelleher FC, O'Sullivan H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors, developmental corruption and malignant disease[J]. Carcinogenesis. 2013, 34(10):2198-205

[29] Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases[J]. Cell. 2010, 141:1117–1134

[30] Potter JD. Colorectal cancer: molecules and populations[J]. J Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91:916–932

[31] Ikushima H, Miyazono K. TGFbeta signalling: a complex web in cancer progression[J]. Nat Rev Cancer 2010, 10:415-424

[32] Huakang Tu, Thomas U. Ahearn, et al. Transforming Growth Factors and Receptor as Potential Modifiable Pre-Neoplastic Biomarkers of Risk for Colorectal Neoplasms[J]. MOLECULAR CARCINOGENESIS. 2015, 54:821-830

[33] Bellone G, Gramigni C, et al. Abnormal expression of Endoglin and its receptor complex (TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta receptor II) as early angiogenic switch indicator in premalignant lesions of the colon mucosa[J]. Int J Oncol. 2010, 37:1153–1165

[34] Hawinkels LJ, Verspaget HW, et al. Active TGF-beta1 correlates with myofibroblasts and malignancy in the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence[J]. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100:663–670

[35] Li Y, Zhu G, et al. Simultaneous stimulation with tumor necrosis factor-α and transforming growth factor-β1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon cancer cells via the NF-κB pathway[J]. Oncol Lett. 2018, 15(5):6873-6880

[36] Badawy AA, El-Hindawi A, et al. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-α on hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocarcinogenesis[J]. APMIS. 2015, 123(10):823-31

[37] Walker F, Abramowitz L, et al. Growth factor receptor expression in anal squamous lesions: modifications associated with oncogenic human papillomavirus and human immunodeficiency virus[J]. Human Pathology. 2009, 40 (11): 1517–27

[38] Midgley AC, Rogers M, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)-stimulated fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by hyaluronan (HA)-facilitated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and CD44 co-localization in lipid rafts[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry[J]. 2013, 288 (21): 14824–38

[39] Holmes K, Roberts OL, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition[J]. Cell Signal. 2007, 19 (10): 2003–2012

[40] Zygmunt T, Gay CM, et al. Semaphorin-PlexinD1 Signaling Limits Angiogenic Potential via the VEGF Decoy Receptor sFlt1[J]. Dev Cell. 2011, 21 (2): 301–314

Comments

Leave a Comment