Melanoma

Melanoma is a common cancer in the Western world with an increasing incidence. It is the most aggressive and lethal type of skin cancer. The pathogenic features of melanomas include growth and amplification of atypical melanocytes associated with several features, involving self-sufficiency of growth factors, insensitivity to growth inhibitors, evasion of cellular apoptosis, tissue invasion, and metastasis [1] [2]. These melanoma pathogenic events can be triggered by activating oncogenes or inactivating tumor-suppressor genes [3].

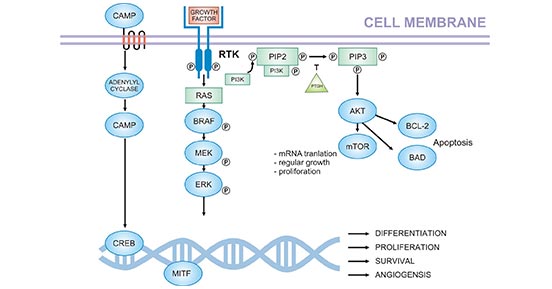

Melanoma is associated with DNA damage and genomic alterations caused by ultraviolet light. An analysis of the gene aberrations in the genome has led to the discovery of the complex interaction of signaling pathways (Figure 1) [4].

Figure 1. Crucial pathways in melanoma pathogenesis (based on current knowledge)

*this diagram is derived from publication on Acta Dermatovenerol Croat [4]

Genetic factors are particularly important for the pathogenesis of melanomas (sporadic and family melanomas). In this article, we list part of these proteins involved in melanoma based on the information provided by NCG (web resource to analyze duplicability, orthology and network properties of cancer genes).

Here, we display several key targets involved in mechanism of melanoma, including:

-

BRAF (Serine/threonine-protein kinase B-raf) is part of a signaling pathway known as the RAS/MAPK pathway, which controls several important cell functions. Accumulating evidence revealed that melanomas of the trunk and limb skin are connected with frequent BRAF (50%) and NRAS (20%) mutations. And lower rates of BRAF mutations (5-20%) and higher rates of KIT mutations (5-10%) have been demonstrated in mucosal and acral lentiginous melanomas [5].

-

RAC1 (Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1) is a 21 kDa GTPase that acts as a molecular switch in a variety of cellular events (such as cell motility, development, signaling, cytoskeletal organization, immune response and cell cycle). RAC1 P29S was recently identified as the third most common recurrent mutation in melanomas, affecting 4-7% of the patients with melanomas. This is an oncogenic mutation, because the mutant protein remains mostly in its active GTP-bound form, and its ectopic expression increases the rate of normal melanocytes proliferation and migration [6].

-

CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A) codes for two proteins, including the INK4 family member p16 and p14arf. Both function as tumor suppressors by regulating the cell cycle. CDKN2A germline mutations are reported to increase the risk of melanoma development and are present in 20 and 10% of familial and multiple melanoma cases, respectively [7].

-

PPP6C (Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 6 catalytic subunit) is one subunit of phosphoprotein phosphatase 6 (PP6), which is a component of a signaling pathway regulating cell cycle progression in response to IL2 receptor stimulation. Recent whole genome melanoma sequencing studies have identified recurrent mutations in the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of serine/threonine phosphatase 6 (PPP6C/PP6C). Moreover, this study also indicated that PP6C mutations were independent of commonly observed BRAF and NRAS mutations [8].

-

ARID2 (AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 2) functions in a chromatin remodeling complex to promote gene transcription. ARID2 depletion attenuated nucleotide excision repair (NER) of DNA damage sites introduced by exposure to UV. In a recent exome sequencing study conducted by our laboratory, ARID2 was found to be mutated in 9% of melanoma samples. Of all the novel melanoma genes identified, ARID2 had the highest loss of function mutation burden-suggesting that ARID2 is likely inactivated in melanoma [9].

References

[1] Kosmidis C, Sofia Baka S, Sapalidis K et al. Melanoma from molecular pathways to clinical treatment: An Up to Date Review [J]. J Biomed. 2017, 2:94-100.

[2] Leong SP, Mihm MC Jr, Murphy G et al. Progression of cutaneous melanoma: implications for treatment [J]. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012, 29:775-96.

[3] Garbe C, Bauer J. Melanoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed., Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012. pp. 1885- 914.

[4] Liborija Lugović-Mihić, Diana Ćesić, Petra Vuković et al. Melanoma Development: Current Knowledge on Melanoma Pathogenesis [J]. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2019, 27(3):163-168.

[5] Ribas A, Slingluff CL, Rosenberg SA. Cutaneous Melanoma. In: Devita VT, Hellman TS, Rosenberg

SA, et al., eds. Principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015. pp. 1346-94.

[6] Ruth Halaban. RAC1 and Melanoma [J]. Clinical Therapeutics. 2015, 37: 682-685.

[7] Blanca De Unamuno, Zaida García-Casado, José Bañuls et al. CDKN2A germline alterations in melanoma patients with personal or familial history of pancreatic cancer [J]. Melanoma Res. 2018, 28(3):246-249.

[8] Gold HL, Wengrod J, de Miera EV et al. PP6C hotspot mutations in melanoma display sensitivity to Aurora kinase inhibition [J]. Mol Cancer Res. 2014, 12(3):433-9.

[9] Flora Luo and Levi Garraway. Functional characterization of ARID2 in melanoma and melanocytes. AACR Annual Meeting 2014; April 5-9, 2014; San Diego, CA.