Antibody-drug Conjugates: A Comprehensive Guide

Traditional chemotherapy for cancer affects both cancerous and normal cells, leading to severe side effects and systemic toxicity. Recent advancements in molecular biology and immunology have improved the understanding of tumor cell biomarkers, allowing for the design of antibodies against tumor-associated antigens (TAAs). Additionally, progress in chemical technology has enhanced the efficiency and stability of antibody-drug coupling, driving the development of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs).

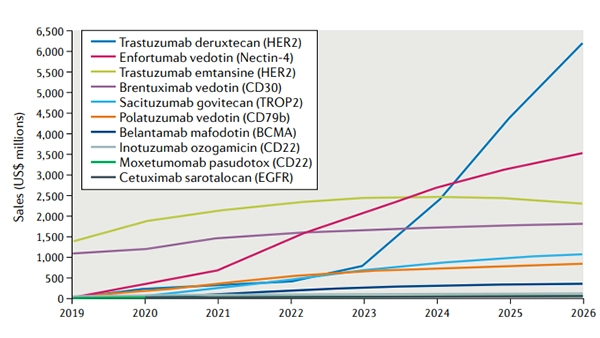

The rising incidence of cancer and the need for more targeted and effective treatments have propelled the rapid expansion of the ADC market in recent years. According to a new analysis from DataM Intelligence, the global ADC market size was valued at $5.0 billion in 2022 and is projected to witness lucrative growth by reaching $16.5 billion by 2030 [1]. The market is expected to exhibit a CAGR of 16.6% during the forecast period (2023-2030).

Figure 1. Forecast global sales of select approved antibody–drug conjugates

Sales from 2020 to 2026 are forecast as of 1 December 2020. Sales of cetuximab sarotalocan reflect the following markets only: USA, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, Japan. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

This article comprehensively and systematically introduces ADC, covering its definition, its advantages, recent advances, common challenges in its evolution, and its working principles.

Table of Contents

1. What Is an Antibody-Drug Conjugate?

ADC is an innovative class of powerful biological drugs that integrate a highly effective cytotoxic drug with a specially designed monoclonal antibody through an appropriate linker. They enable targeted delivery of their conjugated compounds to cancerous tissues while minimizing toxicity to healthy tissues and enhancing the therapeutic benefit for patients.

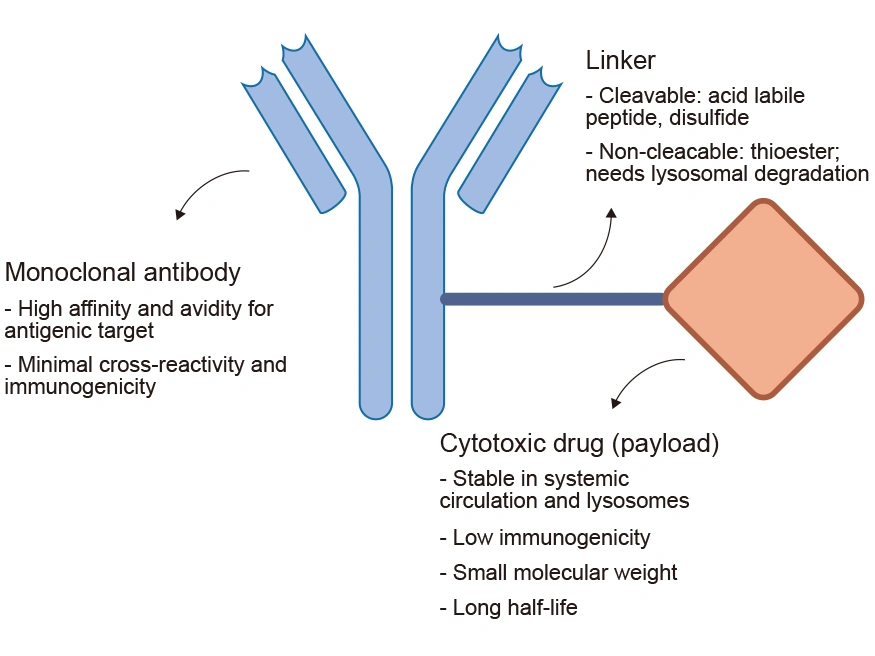

An ADC mainly comprises three components: a monoclonal antibody (mAb) connected to a payload through a chemical linker. The ADC is like a missile with the ability to accurately strike the target. The mAb acts like a missile guidance system. It is engineered to target specific antigens expressed on the surface of cancer cells. The payload is typically a cytotoxic drug with highly anti-tumor properties, similar to a high-explosive warhead of great killing power. The linker is the critical structure that combines the mAb with the cytotoxic drug, akin to the missile’s connection device.

Figure 2. The structure and main components of ADCs

ADCs enable targeted cancer therapy by delivering cytotoxic drugs precisely to tumors, enhancing bioavailability and therapeutic index for improved efficacy with reduced side effects and broad applicability across cancer types.

2. Common Challenges in the Development of Antibody-Drug Conjugates

Common challenges in the development of an ADC include selecting a target antigen and a specific antibody, engineering a stable linker, conjugating potent payloads, and choosing the conjugation methods.

ADC Development Solutions

2.1 Target Antigen Selection

A key aspect of developing a successful ADC for cancer is selecting the specific antigenic target of the mAb component.

The selected target antigen should have four characteristics:

- High expression in tumor cells but minimal expression in healthy cells

- Sufficient density and homogeneity on the surface of tumor cells (minimize the toxicity of on-target and off-tumor) [2]

- Internalization following mAb binding (The target antigen should have internalization capability. This is a particularly important property for ADC target antigens)

The binding site of the targeted antigen should be directed toward the outer surface of the tumor cell rather than the internal area, allowing the circulated ADC to attach to the target antigen before internalization occurs [3]

Target antigens in approved ADCs and selected

ADCs in late-stage clinical development

Target antigens regulated from

driver oncogenes

Target antigens in the tumor

vasculature and stroma

Figure 3. Target Antigens for ADCs in development and in the clinic and developed

2.2 Antibody Selection

The antibody of an ADC determines its duration in plasma circulation, immunogenicity, immune functions, and target specificity.

A selected antibody should possess the following properties:

- High binding affinity to target antigen (facilitate more rapid internalization; However, an antibody with high antigen affinity may, in turn, reduce the penetration into solid tumors.)

- Optimal antibody size

- Humanized antibodies result in significantly reduced immunogenicity

- Maintain a long plasma half-life [4]

2.3 Linker Selection

The linker is the bridge between the mAb and the cytotoxic drug. The ideal linker guarantees adequate stability of the cytotoxic drug in the bloodstream, effectively prevents its premature release, and promotes the targeted release of the drug into tumor cells, thereby improving the overall efficiency and tolerability of an ADC [5]. The design, structure, and chemistry of the linker directly affect the efficacy and safety of the ADC.

Cleavable Linker: e.g., chemically or enzymatically, cleaved after exposure to acidic or reducing environments or proteolytic enzymes, resulting in the release of the cytotoxic payload of the ADC

- Acid-sensitive linker: unstable in acidic conditions

- Peptide-based linker: sensitive to the lysosomal proteases that are generally overexpressed in tumor cells

Cleavable linkers release a payload that may have membrane permeability, which can cause a bystander effect. Approximately two-thirds of ADCs in the current clinical trials use cleavable linkers [6], which are predominantly dipeptide and disulfide linkers.

Non-cleavable Linker: depends entirely on internalization, followed by complete lysosomal proteolytic degradation to release the toxic payload

- Succinimidyl trans-4-(maleimidylmethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC) linker: more stable in blood and release of active metabolite of DM1, lysine-MCC-DM1

- Maleimidocaproyl (Mc)

① If this degradation is not sufficient, the released payload will contain the polar amino acids that connect the linker-payload, which are membrane impermeable and may reduce the bystander effect.

② A non-cleavable linker is better tolerated but less efficacious.

2.4 Payload Selection

The criteria for choosing the ADC payload are solubility, availability to conjugation, stability, and drug potency [7]. ADC payloads should meet several key criteria [8].

- Stable and potent

The payload needs to remain stable during preparation, storage, and circulation. They must target components located within the cells. The active cytotoxic payload should be small, non-immunogenic, and sufficiently soluble in aqueous buffer solutions to ensure optimal conditions for conjugation.

- Main cytotoxic payloads

Payloads should possess a high cytotoxic capacity linked to the pronounced lipophilic nature.

Commonly used payloads:

① Tubulin inhibitors: e.g., MMAE/MMAF (disrupt microtubule function)

② DNA damage agents: e.g., PBD dimers (block DNA replication)

③ Topoisomerase Inhibitors: e.g., Dxd (prevent DNA replication)

④ Immunomodulators: a combination of a precise antibody target with the power of the immune system

2.5 Conjugation Methods

Conjugation techniques used to connect the mAb and payload determine the fast payload release. There are two conjugation methods: stochastic ADC conjugation and site-specific ADC conjugation.

- Stochastic conjugation with naturally occurring amino acids: Pre-existing lysine or cysteine residues

- Site-specific conjugation:

① Engineered reactive cysteine residues

② Introduction of non-natural amino acids

③ Glycan remodeling and glycoconjugation

The drug-antibody ratio (DAR), the number of drug molecules coupled to each antibody molecule, directly affects the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety of an ADC. It is usually determined by the conjugation method used during the development stage. Reasonable optimization of DAR can not only improve the cytotoxicity and biological activity of ADC but also enhance its therapeutic effect.

ADCs generated by stochastic conjugation are usually heterogeneous. The number and position of cytotoxic drug molecules attached to the antibody vary, forming mixtures with different DARs such as combinations of DARs of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Due to the uneven distribution of drugs on the antibody, the therapeutic effect may be unstable, and the response to patients may vary greatly.

Compared with stochastic conjugation, ADCs generated by specific site conjugation have narrower heterogeneity because the drug is only attached at a specific position of the antibody, ensuring that each molecule has a consistent drug load and a defined structure. This consistency helps improve the expected efficacy and safety of the drug and reduces the risk of adverse reactions.

2.6 Antibody internalization efficiency

The internalization efficiency varies for different antibodies. The selection of the antibody-antigen pair with the most suitable internalization kinetics is important.

CUSABIO can provide an efficient tool, the recombinant protein DT3C, to assess the internalization efficiency of antibodies. Researchers can use this DT3C protein to streamline antibody internalization assessment, thus accelerating ADC candidate selection.

This recombinant DT3C protein (CSB-EP360556CQR1) has advantages:

- Evaluate the internalization efficiency of the antibody in vitro

- Simple preparation of mAb-DT3C complexes

- Can be combined with mAbs from multiple sources

- Antibody internalization efficiency is higher than Mab-ZAP

During ADC development, reasonably selecting the above factors can, to some extent, address problems, including short blood residency limiting tumor delivery, low tumor microenvironment permeability, insufficient payload potency, immunogenicity risks, and unresolved pharmacokinetic and safety issues [2,10,12].

3. Recent Advances of ADCs

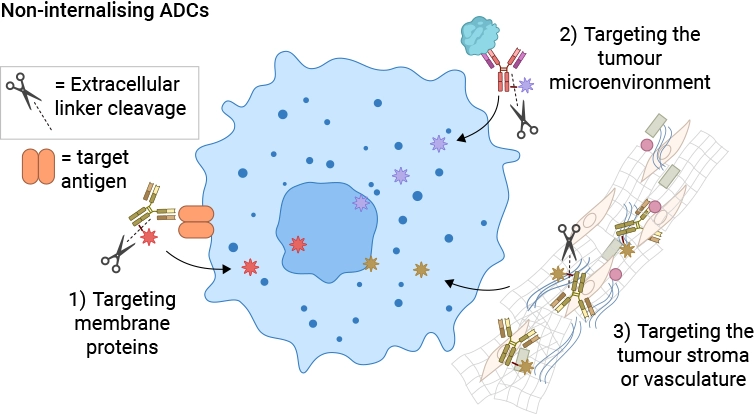

ADCs have revolutionized cancer treatment by combining the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent cytotoxicity of small-molecule drugs. Over the years, ADCs have evolved through three generations, each marked by significant improvements in design, efficacy, and safety. Additionally, emerging innovations such as non-internalizing ADCs are expanding the therapeutic potential of this class of drugs.

Table 1. The evolution of the ADC drug development [2]

|

First-generation ADC |

Second-generation ADC |

Third-generation ADC |

Future-generation ADC |

| Antibodies |

Mouse-original or chimeric humanized antibodies |

Humanized antibodies |

Fully humanized antibodies or Fabs |

Non-internalizing ADCs [11] allow a wider choice of antigen targets:

- Targeting the tumor microenvironment

- Poorly internalizing antibody-antigen interactions

- Cancer Stromal Targeting Therapy for solid tumors

Optimization of the antibody:

- Bispecific antibodies

- Antibody size, e.g., scFv-Fc format

- Immunogenic cell death (IDC)

Advanced linker and conjugation technologies:

- Improved efficacy and minimized side effects

- Increased therapeutic window

Pharmacodynamics/Pharmacokinetics:

- Complex pharmacokinetic profiles due to a heterogeneous mixture of products

- Hydrophobicity balance of ADC

Optimization of payloads:

- RNA polymerase inhibitor

- Dual-payload ADC

|

| Linkers |

Unstable |

Improved stability: cleavable and non-cleavable linkers; |

Stable in circulation; precise control of drug release into tumor sites |

| Payloads |

Low potency, including calicheamkin, duocarmycin, and doxorubicin |

Potency, such as auristatins and mytansinoids |

High potency, such as PBDs, tubulysin, and novel payloads like immunomodulators |

| Conjugation methods |

Random lysines |

Random lysines and reduced interchain cysteines |

Site-specific conjugation |

| DAR |

Uncontrollable (0-8) |

4-8 |

2-4 |

| Representative drugs |

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin and inotuzumab ozogamicin |

Brentuximab vedotin and adotrastuzumab emtansine |

Polatuzumab vedotin, enfortumab vedotin, and fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan |

| Advantages |

- Specific targeting;

- Increase the therapeutic window to some extent

|

- Improved targeting ability;

- More potent payloads;

- Lower immunogenicity;

- Improved targeting ability;

- More potent payloads;

- Lower immunogenicity

|

- Higher efficacy though in cancer cells with low antigen;

- Improved DAR along with improved stability and PK/PD;

- More potent payloads;

- Less off-target toxicity

|

| Disadvantages |

- Heterogeneity;

- Lack of efficacy;

- Narrow therapeutic index;

- Off-target toxicity as premature drug loss; High immunogenicity

|

- Heterogeneity;

- Fast clearance for high DARs;

- Off-target toxicity as premature drug loss; Drug resistance

|

- Possible toxicity due to highly potent payloads;

- Catabolism may be different across species; Drug resistance

|

The evolution of ADCs from first-generation to third-generation therapies has significantly improved their efficacy, safety, and applicability across various cancer types. Innovations such as non-internalizing ADCs and site-specific conjugation strategies are expanding the therapeutic landscape, offering hope for patients with previously untreatable malignancies.

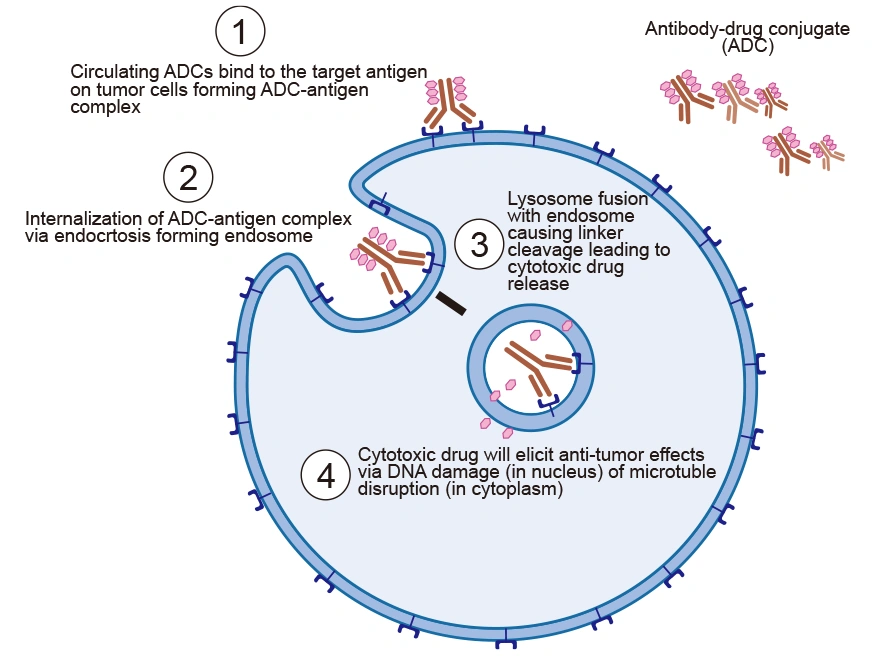

4. How Do Antibody-Drug Conjugates Work?

The tumor-suppressive function of ADCs is primarily mediated by the potency of tumor markers in promoting ADC internalization, rather than by inhibiting cell growth. The mechanism of action of ADCs can be broken down into a series of steps that ensure the selective delivery of the cytotoxic drug to the tumor site.

4.1 ADC Targeting the Tumor Cell

ADCs are intravenously injected into the bloodstream to avoid gastric acid and proteolytic enzyme degradation of mAb. The antibody of ADC recognizes the target antigen on tumor cells and binds to it with high affinity, forming an ADC-antigen complex.

4.2 Internalization of ADC-antigen Complex into Tumor Cells

After binding to the tumor cell, the formed ADC-antigen complex is internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis. The cell engulfs the complex, bringing it into the cell in an endosome.

4.3 Linker Cleavage and Drug Release

After entry into the cell, the ADC-antigen complex in the endosome fuses with the lysosome, which leads to low pH. The acidic environment and lysosomes abundant in proteases such as cathepsin-B and plasmin cleave the ADC, resulting in the efficient release of the free cytotoxic drugs into the cytoplasm.

4.4 Drug Cytotoxicity

The drug is released into the cytoplasm, where it interferes with the cellular mechanisms, induces apoptosis, and eventually causes cell death [9]. The pathway to cell death depends on the type of drug used. For instance, auristatins and maytansinoids disrupt microtubule formation, preventing proper cell division and causing cell death. Calicheamicins and duocarmycins trigger cell death through DNA intercalation.

Figure 4. The mechanism of action of ADC

5. FDA-Approved Antibody-Drug Conjugates

Among the 14 ADCs approved for marketing, six of them are for the treatment of hematological tumors, and the others are for solid tumors (Table 2). More than 100 ADCs are currently undergoing active clinical trials, most of which are in Phase I and Phase I/II. More than 80% of clinical trials are studying the safety and effectiveness of ADCs in various solid tumors, while the rest involve hematological malignant tumors. This indicates that following the success of T-DM1 early and the recent approval of sacituzumab govitecan and Loncastuximab tesirine, research on ADCs has gradually turned into solid tumors in recent years.

Table 2. FDA-approved ADCs [10]

| Drug Name |

Trade Name |

Manufacturer |

Target |

Isotype |

Anyibody |

Linker |

Payload |

Indications |

Approval year |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin |

Mylotarg |

Pfizer/Wyeth |

CD33 |

IgG4κ |

Gemtuzumab |

hydrazone |

Calicheamicin |

Acute myeloid leukemia |

2000, 2017 |

| Brentuximab vedotin |

Adcetris |

Seattle genetics |

CD30

|

IgG1κ |

Brentuximab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

MMAE |

Hematological malignancies relapsed or refractory HL and ALCL |

2011 |

| Trastuzumab emtansine |

Kadcyla |

Genentech/Roche |

HER2 |

IgG1κ |

Trastuzumab |

SMCC |

DM1 |

Metastatic breast cancer |

2013 |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin |

Besponsa |

Pfizer/Wyeth |

CD22 |

IgG4κ |

Inotuzumab |

hydrazone |

Calicheamicin |

Hematological malignancies relapsed or refractory ALL |

2017 |

| Moxetumomab Pasudotox |

Lumoxiti |

AstraZeneca |

CD22 |

IgG4κ |

Moxetumomab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

PE38 |

HCL |

2018 |

| Polatuzumab vedotin |

Polivy |

Genentech/Roche |

CD79b |

IgG1κ |

Polatuzumab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

MMAE |

Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

2019 |

| Enfortumab vedotin |

Padcev |

Astellas Pharma/Seattle Genetics |

Nectin-4 |

IgG1κ |

Enfortumab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

MMAE |

Urothelial cancer |

2019 |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan |

Enhertu |

AstraZeneca/ Daiichi Sankyo |

HER2 |

IgG1κ |

Trastuzumab |

Tetrapeptide based linker |

Dxd |

HER2+ metastatic breast cancer |

2019 |

| Sacituzumab govitecan |

Trodelvy |

Gilead Science/Immunimedics Inc |

TROP2 |

IgG1κ |

Sacituzumab |

CL2A |

SN-38 |

Triple negative breast cancer |

2020 |

| Belantamab mafodotin |

Blenrep |

GlaxoSmithKline |

BCMA |

IgG1 |

Belantamab |

maleimidocaproyl |

MMAF |

Multiple myeloma |

2020 |

| Loncastuximab tesirine |

Zynlonta |

ADC Therapeutics |

CD19 |

IgG1κ |

Loncastuximab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

PBD SG3199 |

r/r DLBCL |

2021 |

| Disitamab Vedotin |

Aidixi |

RemeGen |

HER2 |

IgG1κ |

Disitamab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

MMAE |

Gastric cancer,Urothelial cancer |

2021 |

| Tisotumab Vedotin |

Tivdak |

Seagen |

CD142 |

IgG1κ |

Tisotumab |

mc‒VC‒PABC |

MMAE |

Cervical cancer |

2021 |

| Mirvetuximab Soravtansine |

Elahere |

ImmumoGen |

FRα |

IgG1κ |

Mirvetuximab |

Sulfo-SPDB |

DM4 |

Ovarian cancer |

2022 |

Conclusion

Since the "biological missile" concept emerged, ADCs have undergone significant innovation and optimization, becoming vital in cancer treatment. As more ADCs progress to clinical stages, the industry is shifting from traditional to innovative technologies, focusing on exploring new tumor antigens, antibodies, payloads, linkers, and advanced coupling methods. Continued research will enhance the molecular design of ADCs, improve uniformity and in vivo stability, reduce toxicity, increase efficacy, and expand treatment windows, offering new hope to cancer patients.

CUSABIO ADC Target Antigen Protein Products

Currently, there are 128 ADC targets in development, including 59 with 2 or more pipelines in development. CUSABIO has developed a series of products with different species and tags for various hot targets, which are suitable for immune, antibody screening, SPR, cell activity detection, and other experiments. CUSABIO is committed to assisting you in drug development, and all activity test protocols are available for free. In addition, CUSABIO also provides related research antibodies and ELISA kits.

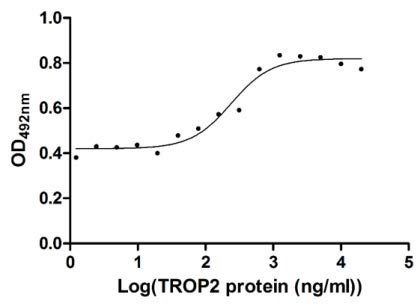

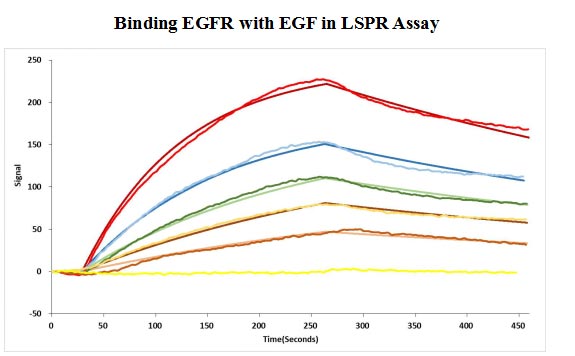

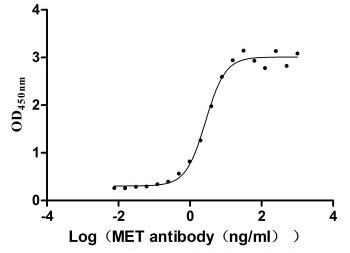

● Partial ADC target Protein Activity Validation Data

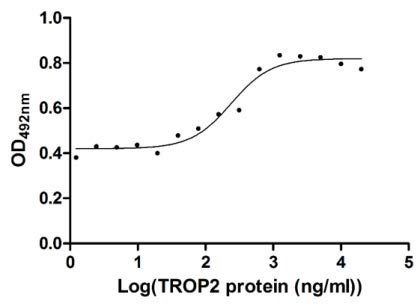

Measured in cell activity assay using U937 cells, the EC50 for this effect is 190.2-298.6 ng/ml.

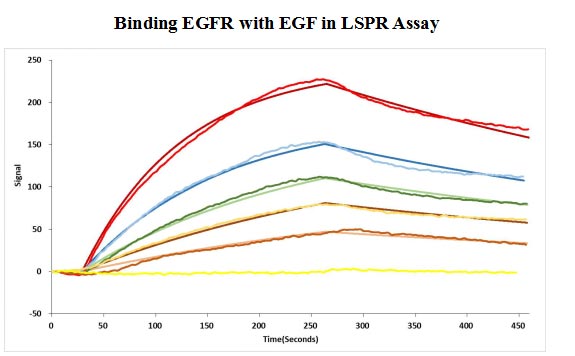

Human EGF protein captured on COOH chip can bind Human EGFR protein, his and Myc tag (CSB-MP007479HU) with an affinity constant of 11.9nM as detected by LSPR Assay.

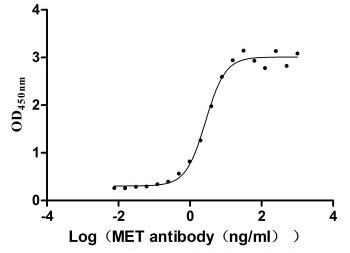

Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. Immobilized MET at 2 μg/ml can bind Anti-MET recombinant antibody, the EC50 is 2.379-3.094 ng/ml.

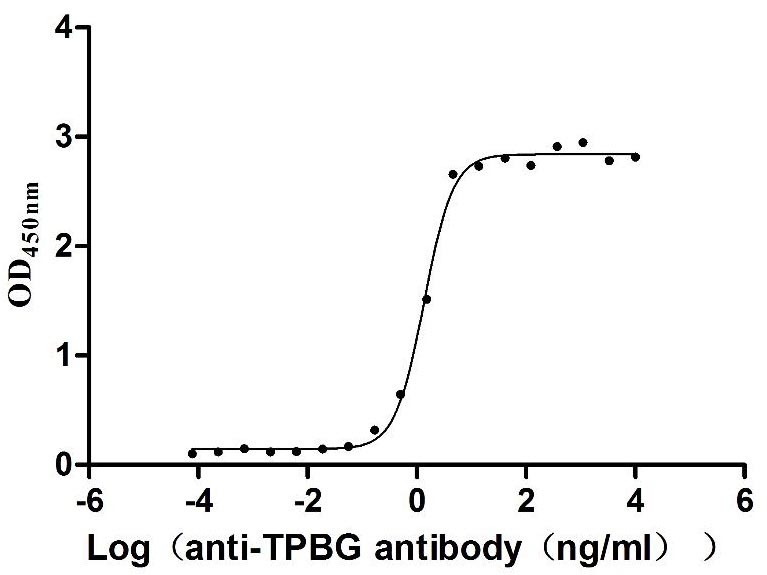

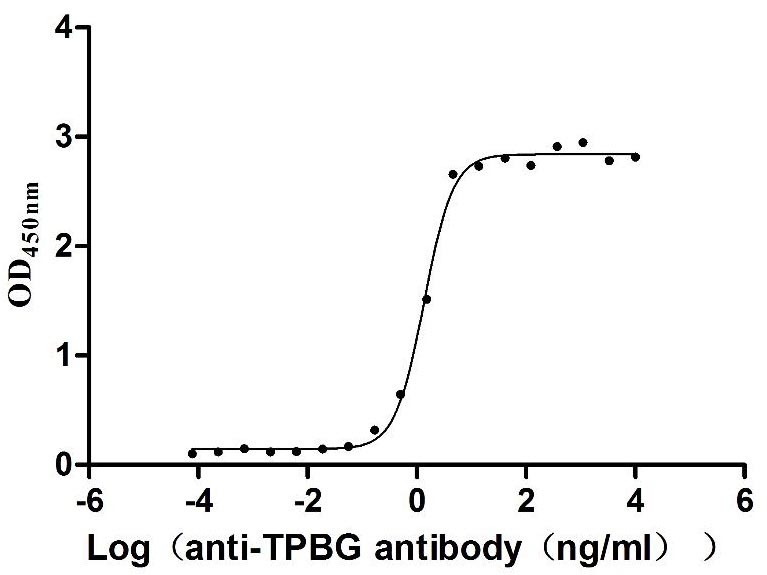

Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. Immobilized Human TPBG at 2 μg/mL can bind Anti-TPBG recombinant antibody (CSB-RA024093MA1HU), the EC50 is 1.230-1.519 ng/mL.

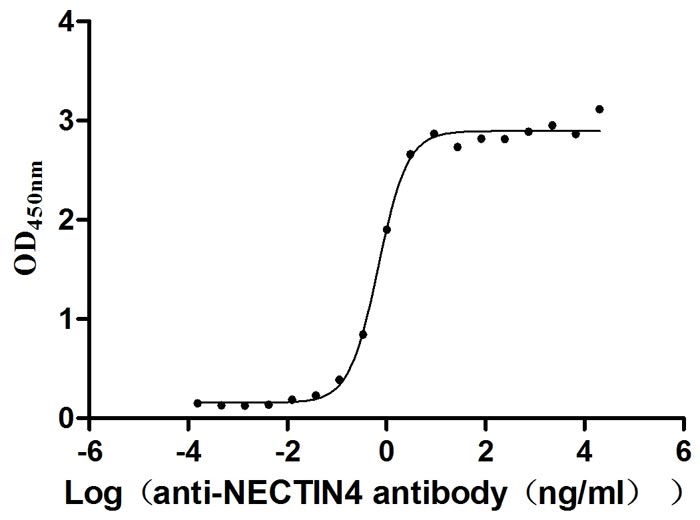

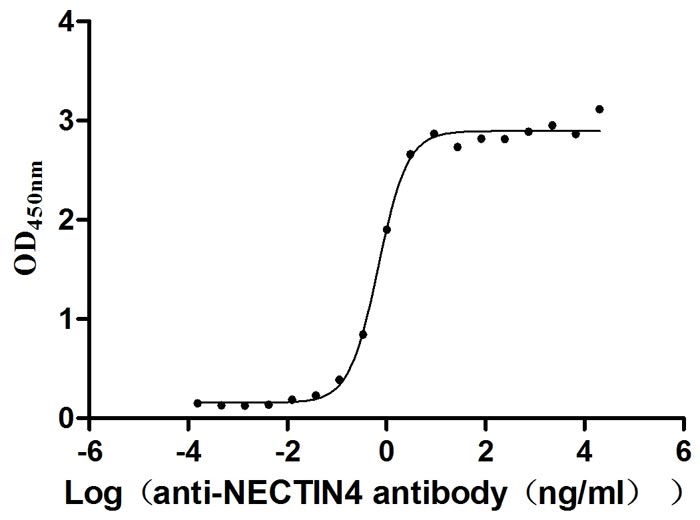

Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. Immobilized NECTIN4 at 2 μg/ml can bind anti-NECTIN4 antibody (CSB-RA822274A0HU) (enfortumab vedotin-like), the EC50 is 0.6029-0.7837 ng/mL.

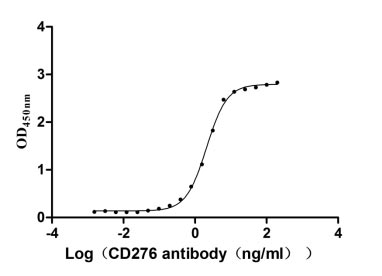

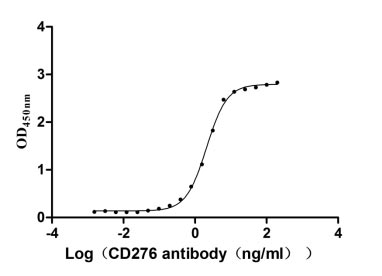

Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. Immobilized CD276 at 2 μg/ml can bind Anti-CD276 rabbit monoclonal antibody, the EC50 of human CD276 protein is 1.961-2.243 ng/ml.

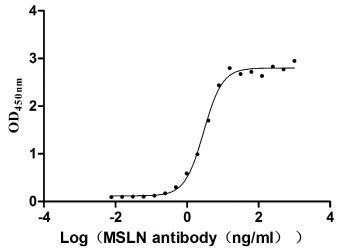

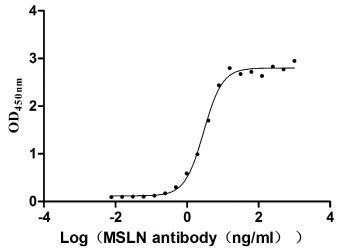

Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. Immobilized MSLN at 2 μg/ml can bind Anti-MSLN rabbit monoclonal antibody, the EC50 of the MSLN protein is 2.657-3.177 ng/ml.

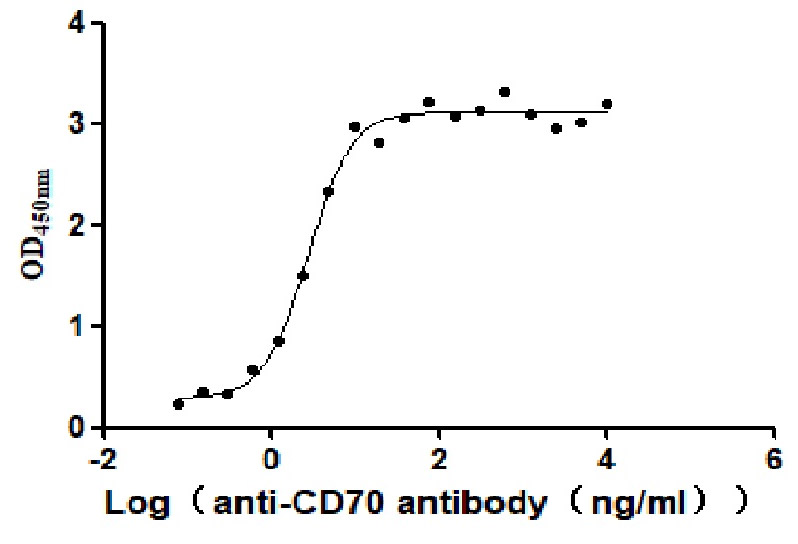

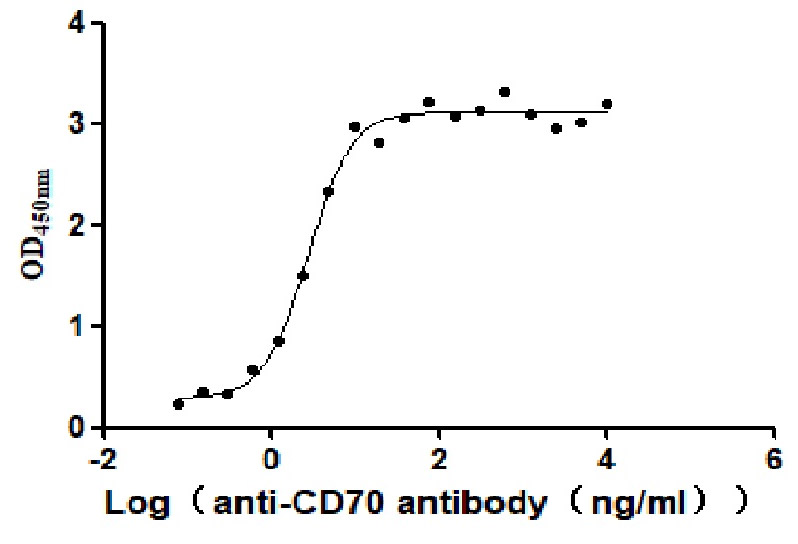

Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. Immobilized Human CD70 at 2 μg/ml can bind Anti-CD70 antibody, the EC50 is 2.414-3.196 ng/mL.

● CUSABIO ADC Target Proteins

| Product Name |

Code |

Target |

Source |

Tag Info |

| Recombinant Human Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO (AXL), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP326981HUd7 |

AXL |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Basigin (BSG), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP002831HU1 |

BSG |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human B-lymphocyte antigen CD19 (CD19), partial (Active) |

CSB-AP005061HU |

CD19 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal Fc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human B-cell receptor CD22 (CD22), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP004900HU |

CD22 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 6xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Signal transducer CD24 (CD24)-Nanoparticle (Active) |

CSB-MP004902HU |

CD24 |

Mammalian cell |

N-terminal 6xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (CD274), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP878942HU1 |

CD274 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human CD276 antigen (CD276), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP733578HU |

CD276 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-Myc-tagged |

| Recombinant Macaca fascicularis CD276 molecule(CD276), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP5140MOV |

CD276 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Myeloid cell surface antigen CD33 (CD33), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP004925HU |

CD33 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-Myc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Membrane cofactor protein (CD46), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP004939HU |

CD46 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Leukocyte surface antigen CD47 (CD47), partial (Active) |

CSB-AP005201HU |

CD47 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 6xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Leukocyte surface antigen CD47 (CD47), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP004940HU |

CD47 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human CD48 antigen (CD48) (Active) |

CSB-MP004941HU |

CD48 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal hFc-tagged |

| Recombinant Human CD70 antigen (CD70), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP004954HU1 |

CD70 |

Mammalian cell |

N-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human HLA class II histocompatibility antigen gamma chain (CD74), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP004956HU1(F2) |

CD74 |

Mammalian cell |

N-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Cadherin-6(CDH6), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP005055HU1 |

CDH6 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Macaca fascicularis Cadherin 6(CDH6), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP4958MOV |

CDH6 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Mouse Cadherin-6(Cdh6), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP005055MO1 |

CDH6 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Rat Cadherin-6(Cdh6), partial (Active) |

CSB-MP005055RA1 |

CDH6 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

| Recombinant Human Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5) (E398K) (Active) |

CSB-MP005165HU |

CEACAM5 |

Mammalian cell |

C-terminal 10xHis-tagged |

CUSABIO has developed the DT3C recombinant protein to aid in screening antibodies with high internalization efficiency for ADC development.

References

[1] do Pazo C, Nawaz K, Webster RM. The oncology market for antibody-drug conjugates [J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021 Aug;20(8):583-584.

[2] Z. Fu, S. Li, S. Han, C. Shi, Y. Zhang. Antibody drug conjugate: the 'biological missile' for targeted cancer therapy [J]. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., 7 (1) (2022).

[3] P. Zhao, Y. Zhang, W. Li, C. Jeanty, G. Xiang, Y. Dong. Recent advances of antibody drug conjugates for clinical applications [J]. Acta Pharm. Sin. B, 10 (9) (2020), pp. 1589-1600.

[4] M. Ritchie, L. Bloom, G. Carven, P. Sapra. Selecting an optimal antibody for antibody-drug conjugate therapy [J]. AAPS Adv. Pharm. Sci. Ser., 17 (2015), pp. 23-48.

[5] Jain N, Smith SW, Ghone S, Tomczuk B. Current ADC linker chemistry [J]. Pharm Res. 2015;32:3526–40.

[6] Lambert, J. M., and Berkenblit, A. (2018). Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer treatment [J]. Annu. Rev. Med. 69, 191–207.

[7] Widdison W, Chari RJ. Factors involved in the design of cytotoxic payloads for antibody–drug conjugates [J]. In: Phillips GL, editor. Antibody-drug conjugates and immunotoxins. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 93–115.

[8] Mahmood, I. Clinical Pharmacology of Antibody-Drug Conjugates [J]. Antibodies 2021, 10, 20.

[9] Kalim M, Chen J, et al. Intracellular trafficking of new anticancer therapeutics: antibody-drug conjugates [J]. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:2265–76.

[10] Liu, K., Li, M., Li, Y. et al. A review of the clinical efficacy of FDA-approved antibody‒drug conjugates in human cancers [J]. Mol Cancer 23, 62 (2024).

[11] Nicola Ashman, Jonathan D. Bargh, and David R. Spring. Non-internalising antibody–drug conjugates [J]. Chemical Society Reviews, Issue 22, 2022.

[12] Fatima, S. W., & Khare, S. K. (2021). Benefits and challenges of antibody drug conjugates as novel form of chemotherapy [J]. Journal of Controlled Release, 341, 555-565.